This table is the cradle of Norwegian democracy

This table played a crucial role during a tumultuous year when Norway faced war, two unions, and three different kings.

When asked by sciencenorway.no about her favourite item in the Eidsvoll building, Solveig Dahl point to this table.

On this table, Norway's first constitution was placed as the Eidsvoll men were called up one by one to sign it.

Contrary to what encyclopaedias and schoolbooks often state, this event did not occur on May 17, 1814. Norwegians celebrate with children's parades, ice cream, and the national anthem on the wrong day.

However, the signing undoubtedly took place on this very table.

“It’s made of solid mahogany and is extremely heavy. It was the Anker family’s dining table,” says Dahl, an art historian and curator at Eidsvoll1814.

A wealthy man and friend of the prince

Carsten Anker was one of Norway's wealthiest men. He ran an ironworks and traded in wood and timber.

“Before moving to Norway, Anker had a long career as a civil servant in Copenhagen. He belonged to the upper echelon of the Danish-Norwegian realm,” says Dahl.

The mahogany table was new around 1750. Anker bought it second-hand in London 50 years later. It was initially at his country house in Denmark before being brought to Eidsvoll.

Anker was a close friend of the Danish Crown Prince Christian Frederik, who led the Norwegian rebellion in 1814.

That year presented new opportunities.

Significant changes

Norway had been a Danish province for 400 years when war broke out in Europe in 1802. The French emperor Napoleon fought against everyone and suffered a decisive defeat. The Danish king, allied with France, also faced defeat.

In January 1814, the peace treaty was signed in Kiel. Denmark had to cede Norway to Sweden, releasing all Norwegians from their oath of allegiance to the Danish king.

“The Swedish king did not have the infrastructure ready to govern Norway, creating a power vacuum. Norwegian politicians took advantage of this,” says Dahl.

The Danish king did not want to give up easily. He sent Prince Christian Frederik to Norway in an attempt to retain the country for the Danish royal family.

21 men met

In February 1814, the prince called in a meeting with his friend Carsten Anker at Eidsvoll.

“Anker was Christian Frederik's most loyal supporter in Norway,” says Dahl.

21 men from powerful families attended. The prince wanted to declare himself king of Norway then and there, but the Norwegians did not want that. They wanted to choose their own king.

"Now the prince has no more right to Norway’s crown than I or any other Norwegian!" professor and politician Georg Sverdrup declared at the meeting.

They decided to convene a national assembly a few months later, where Norway would draft a constitution and choose a king. It was anticipated that Christian Frederik would be the choice.

Many Norwegians opposed a union with Sweden. They wanted an independent Norway.

“Christian Frederik led a rebellion against what the decisions made by greater powers regarding Norway,” says Dahl.

A gathering among white planks and fir branches

In April 1814, 112 men from almost every part of the country gathered at Eidsvoll.

“There was plenty of space. Anker had one of the largest houses in the country,” says Dahl.

Dahl leads the way into the national hall where it all took place.

The room is surprisingly small and simple. The walls are painted white planks, and the floor appears to be untreated.

The hall looks much like it did in 1814, though the fir branch decorations are now made of plastic.

“It was a tradition in Norway to decorate with fir branches, especially at funerals,” says Dahl.

Magistrate Gustav Blom, a representative from Holmestrand, was puzzled by the decor.

He wrote in his diary: After two hours of waiting, we were called into the national hall, which was covered with fir branches on all walls. Are we attending a funeral?

Everything was turned upside down

With so many guests, Carsten Anker's house was turned upside down. Furniture was moved around to accommodate the meetings.

The mahogany dining table was moved to a room next to the hall. It was used by the constitutional committee of 15 men tasked with drafting the new constitution.

Simple tables and benches were brought into the dining room. There, the 112 officials, businessmen, priests, farmers, and officers ate two meals a day.

Magistrate Arnoldus Koren from Bergen wrote to his wife: We sat without regard to status or rank, on wooden benches at long, simple tables. We were served three courses: first, a hearty brown meat soup with finely chopped cabbage ... Then roast veal, and finally a bread pudding.

There was half a bottle of red wine for each, although refills were possible, according to Koren.

For the 2014 anniversary, the accounts for the national assembly were revealed, showing that large quantities of wine and spirits were ordered.

“Journalists have since been interested in how much alcohol was consumed at Eidsvoll, but they forget that many more people than just the representatives visited the house during those weeks,” says Dahl.

There was a substantial operation supporting the national assembly. Drivers and farmers transported the representatives from nearby farms where they were staying. Merchants and couriers delivered goods. Servants and cooks prepared large quantities of food, cleaned, and kept the house in order.

The battle for Norway's future

“They quickly got to work,” says Dahl.

According to a second-grade textbook, 112 men from all over Norway gathered at Eidsvoll to draft a constitution. By May 17, 1814, the constitution was completed.

An eight-grade textbook notes that a Danish prince initiated the national assembly to become king himself. However, it does not mention the intense conflicts that raged in the white-painted hall.

The majority belonged to the Independence Party, nicknamed the Danish Party by their opponents. They wanted Norway to become a fully independent state. Their path to independence was to choose the Danish prince as their king.

The Union Party was called the Swedish Party. Many of its members had opposed the autocratic Danish king. They also wanted independence but did not believe they could avoid the peace treaty and union with Sweden. Therefore, they sought a constitution that would strengthen Norway’s position within the union.

The Independence Party won by a wide margin.

How liberal was the law?

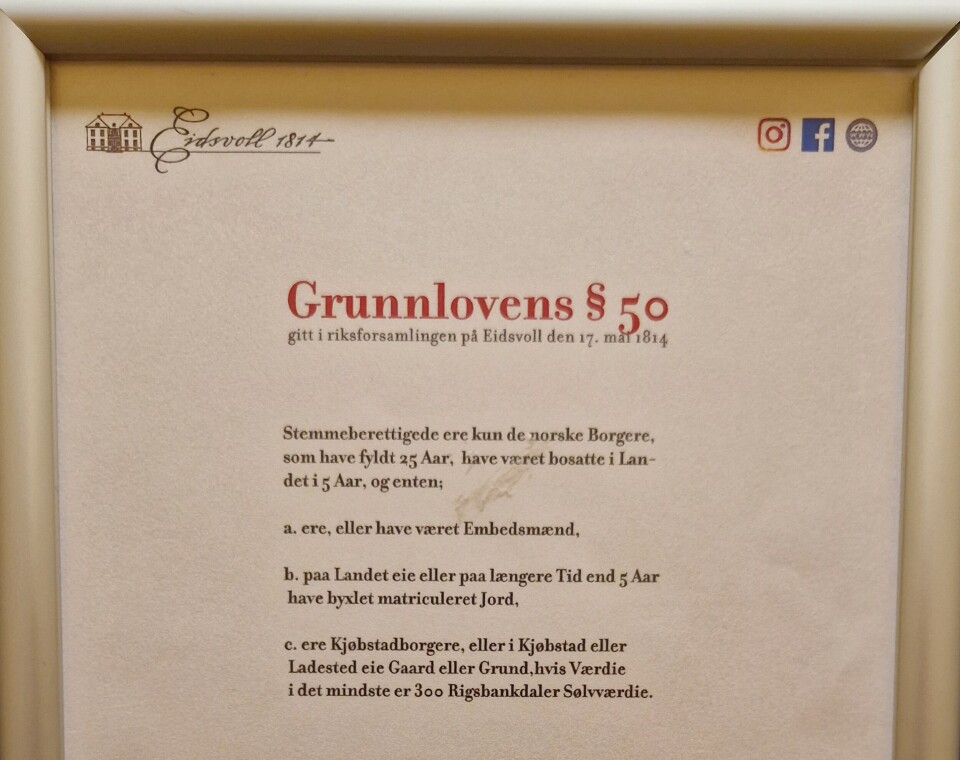

The new Norwegian constitution drew inspiration from the French and American ones. It established that power in the country should come from the people through elections, not from an absolute monarch. The constitution also divided power among the parliament, government, king, and judiciary.

However, only a small fraction of the population gained voting rights.

Only 20 per cent of the population was granted the right to vote under the constitution.

“For its time, it was a liberal constitution with liberal voting rights. But these rights were still tied to gender, property, and income,” says Dahl.

The Eidsvoll delegates eventually reached an agreement. But a document is not valid until it is signed. That happened on May 18.

They spent May 17 electing Christian Frederik as king.

A full day for signing

‘The constitution was adopted on the 16th, finalised and dated on the 17th, and signed on the 18th. Norway's national day is set on the date when a Danish crown prince was elected Norwegian king,’ historian Carl Emil Vogt writes.

The signing process took the entire day. Each man signed and placed his seal. Sailor Even Thorsen could not read or write, so he received assistance.

The historic signing took place on the mahogany table, but it’s unclear if it happened in the national hall itself.

“The table could have been moved into the hall for the signing, or they might have gone into the blue room to sign there,” says Dahl.

Surprisingly little is recorded about the actual signing in the sources from those days in 1814. Were the 112 men solemn when they signed? Were they tired? Were they worried about the future?

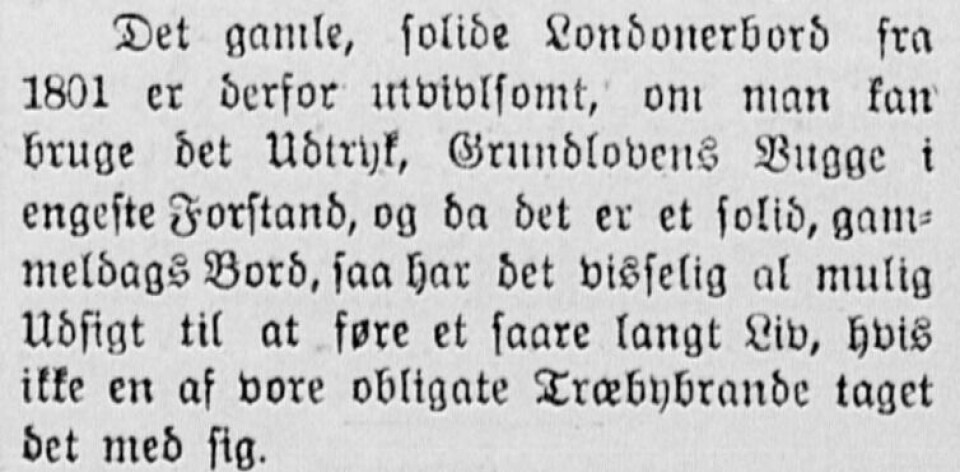

The table disappeared from the Eidsvoll building for a few years but later returned. It was then dubbed the Cradle of the Constitution in Morgenbladet:

The year everything changed

1814 was a truly extraordinary year.

“Norway had three kings in one year, two unions, and a war,” says Dahl.

From January to May 18, Norway was under Denmark and King Frederik VI. Then, the country was independent until October 10 with the new king, Christian Frederik. After that, Norway entered a union with Sweden, with Karl II as king.

During the summer, there was a war. The Swedes had 45,000 soldiers, double the number of the inexperienced and poorly equipped Norwegians. They fought in Kongsvinger, Fredrikstad, Halden, and Hvaler. By August 14, it was over. Sweden won.

“Christian Frederik quickly lost popularity. The Norwegians felt he surrendered too quickly,” says Dahl.

It ended as the so-called Swedish Party had predicted.

“In the long run, the Union Party was right, even though they were in opposition in the national assembly and lost the votes,” says Dahl.

The union with Sweden was different from the one with Denmark. The constitution secured Norway a certain degree of independence.

“The Swedish king allowed Norwegians to keep large parts of the constitution. And Norway gained considerable independence, with its own government and parliament,” says Dahl.

Bankruptcy

A few years after 1814, Carsten Anker went bankrupt.

“He was 75 years old and had to auction off everything he owned. All the furniture, pictures, vases, silverware, and kitchenware disappeared,” says Dahl.

Fortunately, detailed catalogues were made for the auction, describing the furniture and objects in detail, including their original locations in the house.

The house was handed over to English creditors but stood empty until 1837.

Several people found this unacceptable. They founded a society and raised funds to preserve the building and make it a national monument.

The society bought the house, two side buildings, and 25 acres of the property.

From house to museum

Transforming the empty house into a museum took time. In 1851, the Eidsvoll building was given as a gift to the Norwegian parliament.

The house was renovated for the 50th anniversary in 1864, but not to restore it to its original state. Old wallpaper was removed and replaced with newer, more modern ones. The walls in the national hall were covered with green canvas.

“Their main concern was making the hall beautiful and hanging portraits of the Eidsvoll delegates. They were less concerned with the rest of the house,” says Dahl.

After the anniversary, the house went into a period of dormancy.

Horrified by the empty house

Most viewed

“Interest has fluctuated, peaking around each anniversary,” says Dahl.

Nevertheless, some visitors did stop by.

“One of them was bookseller Albert Lange. He was horrified by the bare walls and empty rooms. So, he began enthusiastically collecting furniture and objects,” says Dahl.

Lange appealed to the public through newspapers, asking people to donate items that had belonged to Carsten Anker or dated back to 1814. Many different items were donated, though not all were verified to have actually been in the house at Eidsvoll.

The house was refurnished and renovated once again. This time, the focus was on making it look stately, according to Dahl.

The mahogany table made its return.

Last surviving witness confirms the table

“Carsten Anker's son and wife attended the auction after his bankruptcy. They bought some furniture, items, and cows,” says Dahl.

One of the pieces of furniture was the mahogany table. It had been moved from house to house but remained in the family. They had been told that this was the very table used for signing the constitution.

But could they be absolutely sure?

The family contacted Thomas Konow, who was the surviving eyewitness. He had been the youngest representative in 1814, only 18 years old at the time.

Konow examined the table. More than 50 years had passed since he stood before it and signed the constitution.

He could not be certain it was the same table, but he ‘found it highly likely, as he remembered that the signing took place on a large, beautiful table.’

Carsten Anker’s grandson had a commemorative plaque made in silver and donated the table to the house in 1895. The plaque reads: ‘The Kingdom of Norway’s Constitution of May 17, 1814, was signed on this table.’

Is the Eidsvoll building worth a visit?

During the summer, most visitors to Eidsvoll 1814 are families with children, according to Solveig Dahl. However, it also attracts others interested in the building or Norwegian history.

“Here, you can hear the story of what happened in 1814 and why it happened here. Many are surprised to learn that the constitution was written and adopted in a private home,” says Dahl.

For the 2014 anniversary, the house was restored and returned to its original state.

“As it stands today, it reflects the Anker family's home as it was around 1814,” says Dahl.

———

Translated by Alette Bjordal Gjellesvik

Read the Norwegian version of this article on forskning.no

Reference:

Fure, E. Eidsvoll 1814. Hvordan Grunnloven ble til (Eidsvoll 1814. How the Constitution was created), Dreyer, 2013.

Heidenreich, V. & Moe, M.J. Relevans 8. Samfunnsfag for ungdomstrinnet (Relevance 8. Social studies for lower secondary school), Gyldendal, 2020.

The story of 1814 in 1-2-3, eidsvoll1814.no.

Vogt, C.E. Herman Wedel Jarlsberg. Den aristokratiske opprøreren (Herman Wedel Jarlsberg. The aristocratic rebel), Cappelen Damm, 2014.