Internet sparks local political engagement

Social media are among the new forms of e-democracy that are taking hold in Norway and elsewhere. And the public increasingly expects online access to their politicians and communities.

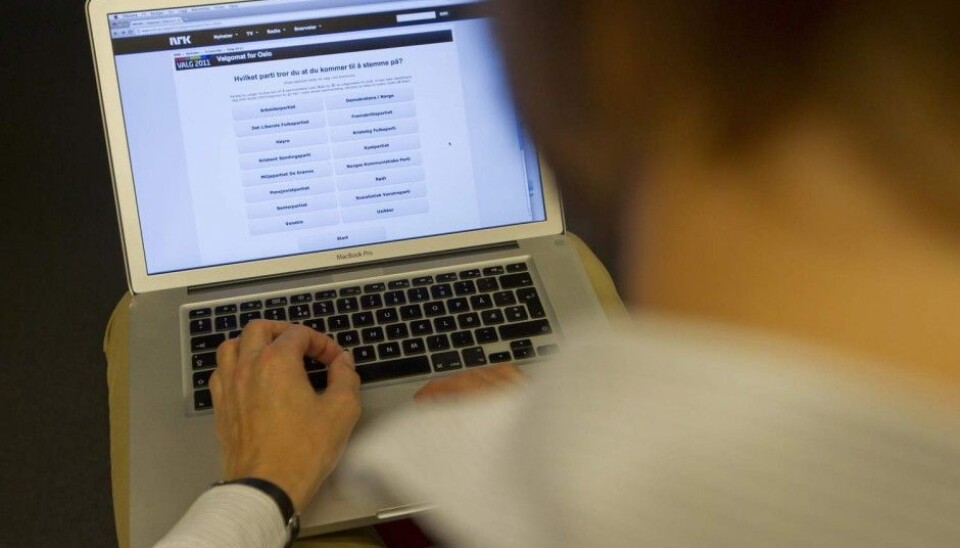

Selected Norwegian municipalities tested the use of remote Internet voting (or e-voting) in the 2011 local government elections and the 2013 parliamentary elections. Despite positive reports, Norway’s Minister of Local Government and Modernisation, Jan Tore Sanner, last year shelved further trials.

Why? And how else is the Internet being used in the political realm? Forskning.no, the online site for Norwegian and international research news, asked a researcher and two municipal employees to address e-voting concerns and how municipalities continue to broaden their use of online tools to engage with their constituencies.

Electronic democracy is here to stay

Enthusiasm for e-democracy has come in waves over the past decade in Norway. Signe Bock Segaard, a researcher at the Institute for Social Research, says that in the mid-2000s municipalities had big ambitions to use the Internet to address issues and have a dialogue with citizens.

Although the initial wave of enthusiasm waned as the technological novelty wore off, the Internet generated new expectations.

“In evaluating the e-voting trials, we found that society is evolving and coming to expect their politicians and local authorities to be accessible online. If they fail to keep up with the times, their legitimacy might suffer,” Segaard said.

E-voting secrecy posed a stumbling block

According to Segaard, the difficulty of implementing secret ballots from home was one of the reasons that e-voting has been put on hold. Secrecy of the ballot is not only a right on the part of the voter but also an absolute obligation in Norway.

She says that other countries have made considerably more progress with electronic voting than Norway. “In Estonia, the Supreme Court said that the principle of the secret ballot is to be understood as a right rather than an obligation. This has facilitated electronic voting there,” she says.

Social media come into focus

With e-voting trials shelved in Norway, other ways to use the Web are coming into the spotlight. The Agency for Public Management and eGovernment (Difi), the Ministry of Local Government and Regional Development and The Centre of Competence on Rural Development

have all provided website development help to municipalities throughout Norway.

The result is easier access to municipal information and proceedings, mailing lists and local council meeting transmissions. Some municipalities include political parties’ own web pages on the municipality’s site, and other municipalities separate politics and local administration.

With several Facebook pages, Nesodden municipality exemplifies the progressive approach taken by numerous communities to staying in touch with their residents. Marianne Rand-Hendriksen is Nesodden’s communications adviser, and says that the municipality is developing a new communications strategy and common guidelines for staff use of social media.

“We have posted this proposed strategy and invited comments from the community,” she says. “We’re trying to use the media forms that people use the most. This is a good way to find out what people are thinking about.”

As Rand-Hendriksen sees it, “the web pages are the information hub, and the Facebook pages are the spokes.”

Source of new policy ideas

Mayor Nina Sandberg also has a strong web presence in Nesodden municipality.

“I’m used to using social media and find it valuable. The suggestions that come to me may later enter the political dialogue,” she tells forskning.no. The refugee crisis is one recent example. It has aroused enormous interest and a desire to help among Nesodden residents.

“This is a great way to gauge the political course and get ideas for new policies,” Sandberg says.

Too time consuming?

In Sandberg’s opinion, social media has proven manageable and useful and is not taking too much of her time. Danish experiences with transmitting audio and video recordings of hearings confirm her opinion. The initial fear of too much public input didn’t happen, Segaard said.

“As in the mid-2000s, perhaps some individuals believe that the technologies, rather than the issues, are motivating people to engage,” she said. “But technology on its own isn’t going to keep the communication channels open.”

Segaard also believes that it is still an open question whether social media will take too much of politicians’ and municipal employees’ time.

And she wonders whether politicians could become too cautious about what they say if everything said in council meetings is transmitted to residents and stored as sound for the future. This could hamper the political process, says Segaard.

Many still want e-voting

Although experiments with electronic voting in Norway have stopped for now, Segaard anticipates that the topic will surface again, at least aspart of the debate on democracy and accessibility.

“Studies show that a large part of the population believe that this is the future of voting,” she says.

-------------------------------------

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no