Why do so many voters around the world vote for authoritarian men?

These voters voluntarily give their vote to politicians who are not particularly interested in democracy.

Donald Trump openly attempted to sabotage the results of the last democratic presidential election in the United States.

A majority in the country might nonetheless elect him as their president again on November 5th this year.

Trump off to Argentina?

If Donald Trump is inaugurated as the 47th president of the USA, one of the first things he plans to do is make a state visit to Argentina.

That plan is according to Trump-inspired ‘anarcho-capitalist’ Javier Milei, who in November was elected president of the South American country by a large majority.

"I am very proud of you. You will turn your country around and truly make Argentina great again," Trump said in a video on social media shortly after Milei was elected.

But Javier Milei is not the first politician Trump has inspired and been able to congratulate on an election victory in the almost ten years he has had an influence on global politics.

Argentina's new president is unlikely to be the last either.

Brazil, India, and Hungary

Jair Bolsonaro, often referred to as the Trump of the Tropics, was president of Brazil until 1 January 2023, imitating Trump both in style and politics.

Bolsonaro has been labelled a right-wing populist. In the 2022 presidential election, he received 49 per cent of the votes and thus narrowly lost to the popular former president Lula da Silva.

Bolsonaro was behind what many considered a disastrous handling of the Covid-19 pandemic in Brazil, a somewhat similar situation to what may have cost Trump the election victory against Joe Biden. Bolsonaro let his supporters storm the Congress in Brasilia, inspired by what Trump set in motion in Washington.

In India – regarded as the world's largest democracy – Prime Minister Narendra Modi has increasingly tightened his grip on power. This spring, he could become the election winner for the third time in a row.

Even though Modi came to power before Trump, many have observed parallels in their leadership style.

Viktor Orbán has been Hungary’s prime minister for 18 years. In the 2022 election, his party received support from 54 per cent of voters. Orbán has long been a leading figure in European right-wing populism and – like Trump – uses nationalism and anti-immigration to gather votes. Hungary is now an 'illiberal democracy', according to Orbán’s own description.

Most viewed

No content

Many believe Trump has inspired other politicians as well, such as former Prime Minister Boris Johnson in the UK, Rodrigo Duterte in the Philippines, and Matteo Salvini in Italy.

What can explain this trend?

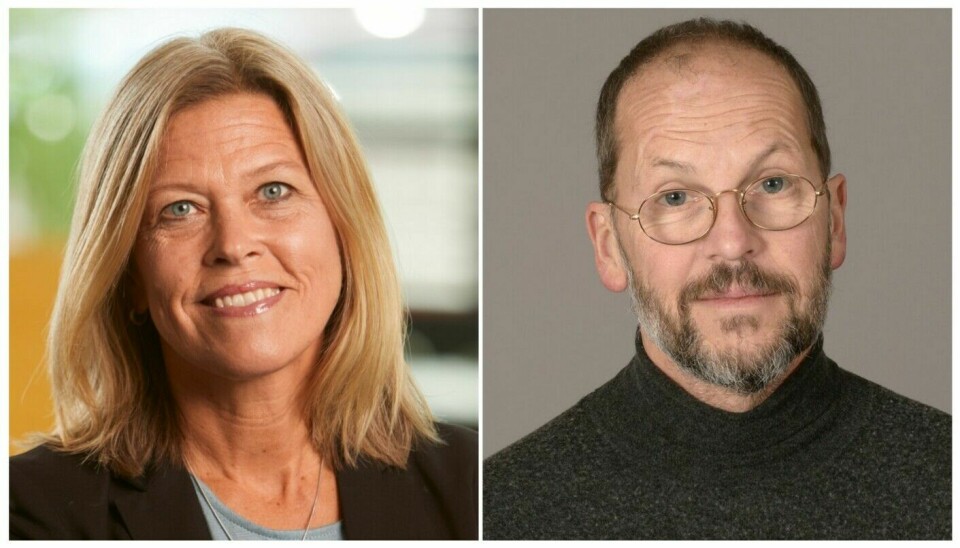

Populism is perhaps the most important keyword to try to understand what is happening, according to Benedicte Bull and Arild Engelsen Ruud, two professors at the University of Oslo.

On March 19th, they will participate in a free event entitled ‘Why do millions vote for authoritarian men?’ at Deichman Bjørvika, Oslo’s Public Library.

Anti-elitism is another important keyword.

Opposition to immigration also plays a role.

So do gender politics.

Many voters also want a strong leader who can ‘clean up’.

Populism as a political strategy

Political scientist Benedicte Bull views populism as a strategy primarily used to mobilise disaffected voters.

“Populism divides people into ‘good’ and ‘bad.’ It also promotes individual leaders as the people's salvation,” she says.

“Additionally, populism is used to undermine people's trust in institutions, including the judiciary, the bureaucracy, the national assembly and the electoral system.”

Left-wing populism

Bull points out that there is limited agreement on what the word populism really means.

"To some, populism can be seen positively, like mobilising poor people in a country with much social and economic inequality," she says.

If we look back a few years, it was mostly left-wing politicians who used populism as a strategy to mobilise dissatisfied voters.

“Venezuela was the first such example in Latin America. But we’ve also seen elements of populism in Bolivia, Ecuador, and Argentina,” she says.

Right-wing populism

Right-wing populism has now made the most significant gains around the world.

Two examples are Bolsonaro in Brazil and newly elected Milei in Argentina.

However, Bull points out that these two politicians are very different from one another and have different political agendas.

“But they both get a lot of their populist repertoire from the USA and Trump,” she says.

Milei's message about a corrupt elite neglecting their country is inspired by Trump and has resonated with many voters in Argentina.

He has also followed Trump in issues like gun rights, abortion, feminism, and gender issues. And like Trump, Milei has made allegations that political opponents engage in electoral fraud, without any substantial evidence.

Attacks on the society's elite

Like Bull, Arild Engelsen Ruud is a professor at the University of Oslo. His expertise is in the politics in Asia.

Ruud believes that anti-elitism is at the heart of a lot of populism, where people are mobilised to push back against a real or a fictional elite in society.

“In a lot of countries, a large part of the population feels that the liberal elite in society pushes values that they find foreign. This elite could, for example, be linked to universities or be public servants,” he says.

Gender politics provokes

"The idea that there can be more than two genders, that men and women should be equal in all areas – and a lot of other things – provokes people,” says Ruud.

In India, many perceive the elite's secular ideas as anti-Hindu.

The respect for minorities is seen as going too far.

Right-wing populists in several countries use such issues to mobilise voters.

But you can also find populists on the left in Asia, Ruud emphasises.

In Asian countries, it can be difficult to say whether a regime should be classified as right or left of the political spectrum.

In both Asia and Latin America, the two researchers also see how populist politicians use the fear of crime, especially organised criminal gangs, to secure support from large groups of voters.

Constantly critical of the media

Another important characteristic of populist leaders is their constant criticism of the media.

The media is often accused of being part of a large conspiracy in society.

“Behind this conspiracy is a liberal elite or a capitalist elite, depending on whether you're talking about right-wing populism or left-wing populism,” says Bull.

“A left-wing populist like Nicolás Maduro in Venezuela blames US imperialism and all its followers for most issues. While for Bolsonaro in Brazil and Milei in Argentina, the main enemies are left-wing elites. These are found in the Brazilian Workers' Party and the Argentine Peronist Party, respectively."

Authoritarian capitalism

Bull points out that authoritarian populism also has another feature: the countries' economic policies.

Because when societal institutions are constantly undermined by an authoritarian leader, the country's business and economy are instead more personally managed by the leader.

The business sector is still driven by the motive for profit.

But the authoritarian leader is the one who decides who receives investment opportunities, contracts, and privileges.

The authoritarian leader demands political loyalty from the recipients.

“But this isn’t inspired by Trump,” says Bull. “If we're talking about international inspiration here, it tends to come from leaders like Erdogan in Turkey, Orbán in Hungary, and Putin in Russia.”

Indian prime minister uses social media

A few years ago, many countries in South Asia and Southeast Asia were moving in an increasingly democratic direction.

Asia expert Arild Engelsen Ruud now observes how this trend has reversed.

He sees several possible reasons for the decline in democracy in Asia.

“India is holding an election in a few months. This is happening in a country that has clearly moved in a less democratic direction,” the researcher says.

“The ruling Hindu-nationalist party BJP now employs a wide range of methods to suppress the political opposition.”

Ruud also points to how Prime Minister Modi and the BJP use social media very actively to attack opponents, whether they be political rivals, Muslims, or Christians.

Popular to shoot drug dealers

“Matters have gone even further in the neighbouring country Bangladesh. It is now in reality an authoritarian ruled country where opposition politicians are imprisoned before elections are held,” Ruud says.

“The Philippines is also a very interesting country to follow.”

The controversial politician Rodrigo Duterte won the election in 2016 after stating that as president he would kill up to 100,000 criminals.

When Duterte retired from political life, Bongbong Marcos, the son of the country's former dictator Ferdinand Marcos, was elected as the new president last year.

“Allowing the police to shoot drug dealers in the streets turned out to be popular among the public. Police may have killed as many as 10,000 people in this way during Duterte's rule," Ruud says.

“Bongbong has actually proven to be less violent and less authoritarian than Duterte. To a certain extent, the Philippines has moved in a positive direction."

Social media is also actively used in the Philippines to promote populist messages.

Perceive themselves as the majority

Arild Engelsen Ruud observes another interesting commonality in countries with populist and authoritarian leaders.

"Whether people are storming the Capitol in the USA, supporting the oppression of minorities in India, or wanting the police to kill suspected drug dealers in the streets of the Philippines, these are people who think of themselves as a natural majority in the population," he says.

“I think this is an important factor in many authoritarian leaders’ support. People who support them want their country to be the country of the majority, not the country of minorities.”

Minorities encompasses everyone from homosexuals to Christians or criminals.

Ruud believes this can also explain why anti-elitism is such an important factor in global right-wing populism.

“In a country like India, this view can also explain why so many people in the population think it’s okay to oppress other groups, whether they’re Muslims, Christians, or casteless,” he says.

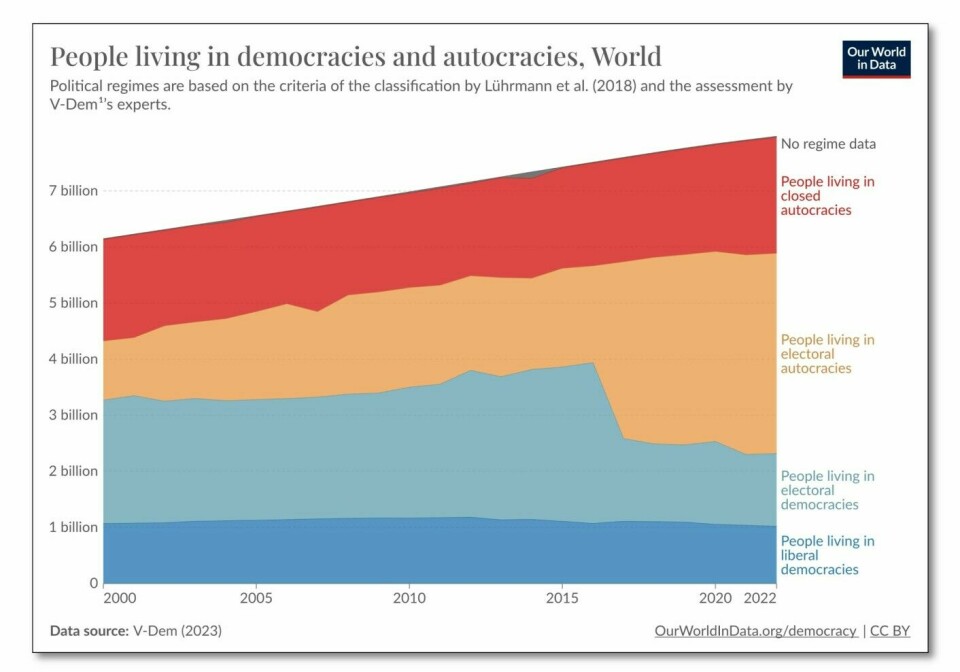

Most people in the world do not live in a democracy

Around the year 2000, well over half of all people in the world lived in a country that could be called democratic.

Today, about 2.3 billion people live in a democratic country.

A total of 5.5 billion people live in a country with an autocratic regime.

The graph below was created by the Our World in Data project at the University of Oxford in the UK. It is based on figures from the V-Dem research project at the University of Gothenburg.

- Liberal democracies: Well over a billion people in the world live in the most democratic countries – liberal democracies – such as Norway. This number has remained fairly stable since 2000.

- Electoral democracies: However, the number of people living in so-called electoral democracies has more than halved in recent years. In electoral democracies, people get to participate in free and fair elections. But the citizens do not have the same democratic protection as in Norway and other liberal democracies. Argentina and Mexico are two such examples.

- Electoral Autocracies: Instead, the number of people living in what are called electoral autocracies has doubled. Here, citizens can participate in elections. But they do not have the freedom to organise and express themselves, which is necessary if political elections are to be considered free and fair. It therefore does not make sense to call these countries democratic. India and Turkey are examples.

- Closed autocracies (dictatorships): The proportion of people in the world who live in pure dictatorships – called closed autocracies by researchers – has increased somewhat in recent years. China and North Korea are such examples.

Reference:

Our World in Data: 'How Many People Live in a Political Democracy Today?', 11 April 2022.

———

Translated by Ingrid P. Nuse

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no