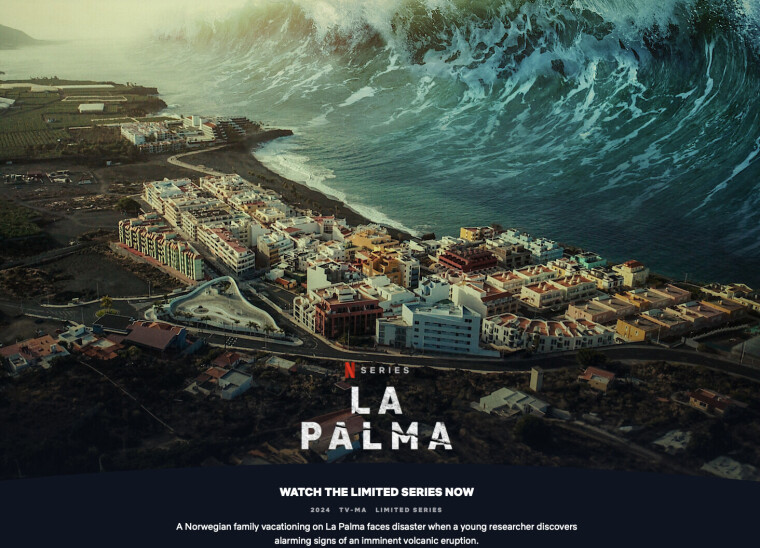

What's real and fictional in Netflix's disaster series La Palma

The Norwegian series La Palma has become one of the most popular series on the streaming service Netflix. But how realistic are the volcanic disaster and tsunami?

First, the volcano erupts.

Then, large parts of the island collapse into the sea.

This creates a giant tidal wave. In La Palma, the tsunami destroys much of the Canary Islands and the city of New York on the other side of the Atlantic Ocean.

Volcanologists Marie from Norway and Haukur from Iceland have tried to warn the authorities in Spain and Norway about what is going to happen.

They are not listened to.

Less than a month after La Palma premiered on Netflix on December 12, the series had been viewed 58 million times. This makes it one of Netflix's most popular non-English language series ever.

2,600 houses destroyed

The volcanic eruption on La Palma is real enough.

It occurred in 2021. More than 2,600 houses were destroyed. Only one death was indirectly linked to the eruption.

La Palma is the northwesternmost of the Canary Islands.

The fairly densely populated island has about 85,000 inhabitants. The lava from the 2021 volcanic eruption flowed over the island's largest city.

La Palma is the most volcanically active of the Canary Islands.

The island began forming out in the Atlantic Ocean less than two million years ago. In 2022, Spanish researchers discovered a large chamber filled with magma – molten rock – about ten kilometres beneath the island. When magma breaks through the Earth's crust and reaches the surface during a volcanic eruption, it is called lava.

The steepest place on Earth

Lava from deep within the Earth has caused La Palma to rise nearly 7,000 metres from the ocean floor.

The highest edge of the enormous volcanic crater Caldera de Taburiente rises 2,426 metres above sea level.

Measured from the ocean floor, the large and now dormant main volcano on La Palma is even taller. It is approaching the height of Mount Everest.

At the top of the volcanic crater are some of the world's leading astronomical observatories.

The lava masses have made La Palma one of the steepest places on Earth when considering its height relative to its small land area. It's not surprising that something could collapse into the ocean.

The hypothesis of the giant tsunami

The hypothesis that a large part of La Palma might collapse and trigger a giant tsunami in the Atlantic Ocean first appeared in a study published by tsunami researchers Steven Ward and Simon Day in the journal Geophysical Research Letters in 2001.

The study warns that between 150 and 500 cubic kilometres of lava rock could collapse into the sea on the island's western side.

The researchers created a model showing that such a landslide could generate a tsunami up to 900 metres high.

By the time it reaches North and South America on the other side of the Atlantic, the wave could be between 10 and 25 metres high. Perhaps even higher.

This aligns closely with the catastrophic tsunami portrayed in the popular Norwegian Netflix series.

Norwegian researchers have calculated the tsunami

Finn Løvholt is a researcher at the Norwegian Geotechnical Institute (NGI).

In 2008, he worked on his PhD in hydrodynamics.

Løvholt examined the model proposed by tsunami researchers Ward and Day. He did this in collaboration with physicist Galen Gisler and mathematician Geir K. Pedersen at the University of Oslo.

"We found that a landslide of 375 cubic kilometres would not create a 900-metre-high wave as the 2001 study warned. The maximum wave height would be 300 metres in the immediate ocean areas surrounding La Palma," Løvholt tells sciencenorway.no.

"However, this would still be enough to cause catastrophic waves along coastlines in Africa, the Americas, and parts of Europe. The resulting wave heights and destruction could far exceed those of the Indian Ocean tsunami during the Christmas holidays of 2004," he says.

A 9-10 metre wave towards the USA

Løvholt is today one of Norway's leading tsunami researchers.

"When Gisler, Pedersen, and I revisited the model in 2008, our goal was to create a more accurate simulation than what Ward and Day achieved in their 2001 study," he says.

"We aimed to perform a more detailed numerical analysis of wave dynamics," he says.

Løvholt and his colleagues concluded that tsunami heights near coastal regions could reach:

- Approximately 40 metres when hitting the island of Madeira.

- Approximately 33 metres towards the Cape Verde islands.

- 14-15 metres towards South America.

- 9-10 metres towards the southern and central parts of the USA.

- Waves towards Morocco and Portugal could be 'only 5-7 metres high.

Here you can watch the trailer for La Palma.

"However, because the waves become shorter and taller in shallower water, the run-up heights on land can be significantly higher than this," says Løvholt.

"We also cannot rule out that the waves could be lower, primarily due to wave breaking," he says.

Calculating the run-up heights of the waves requires more detailed analyses, which the researchers at the University of Oslo did not explore further, explains Løvholt.

A new mathematical model

In 2008, Professor Geir K. Pedersen at the University of Oslo developed a new mathematical model for how waves spread over large distances in the Atlantic Ocean.

The researchers also focused heavily on understanding the distribution of complex wave patterns.

"This made our calculations more accurate than those of Ward and Day a few years earlier," Løvholt tells sciencenorway.no.

Løvholt, Gisler, and Pedersen also discovered that tsunamis caused by landslides behave differently from those triggered by earthquakes. The 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami was caused by an earthquake.

The wave that struck Thailand and several other countries in Southeast and South Asia was dominated by a limited number of wave peaks.

In contrast, a landslide on La Palma could generate a longer series of large waves spreading across the Atlantic Ocean. These waves would take five to six hours to traverse the ocean and could strike the coasts of North and South America over a period of several hours.

Additionally, the researchers found that the first wave in a series does not necessarily have to be the largest, challenging common perceptions of tsunamis.

14 large landslides in the Canary Islands

Over the course of a million years, Spanish and British researchers have documented 14 major landslides on the Canary Islands. Some of these have been as large as 375 or 500 cubic kilometres.

A Spanish study from 2022 identified five megatsunamis originating from the Canary Islands. Researchers found numerous traces of these tsunamis.

Most viewed

Other studies have concluded that landslides on the Canary Islands often occur gradually, breaking into smaller landslides over several days or weeks.

This gradual process would naturally reduce the size of a potential tsunami.

Another argument against Ward and Day's hypothesis is that no evidence of previous large tsunamis originating from the Canary Islands has been found along the coast of North and South America.

"However, there are significant traces of tsunamis on the Canary Islands and Cape Verde islands. So locally, we know that landslides can create significant waves," says Løvholt.

He also references a study showing that a landslide from the volcanic island of Fogo in Cape Verde 73,000 years ago caused a tsunami with a wave height of over 270 metres to strike the neighbouring island of Santiago.

A La Palma tsunami could still be tall

Even if the waves are not as tall as depicted in the disaster series La Palma, the tsunami researcher at NGI notes that multiple large landslides from the unstable southwest side of La Palma could still generate tall waves.

The wave height would depend on the volume of each landslide.

"Even a landslide just one-tenth the size of what Ward and Day warned about would still be massive and capable of producing tall waves. We’re still talking about catastrophic landslides," Løvholt concludes.

———

Translated by Alette Bjordal Gjellesvik

Read the Norwegian version of this article on forskning.no

References:

Løvholt et al. Oceanic propagation of a potential tsunami from the La Palma Island, Journal of Geophysical Research Oceans, vol. 113, 2008. DOI: 10.1029/2007JC004603

Ramalho et al. Hazard potential of volcanic flank collapses raised by new megatsunami evidence, Science Advances, vol. 1, 2015. DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.1500456

Ward, S.N. & Day, S. Cumbre Vieja Volcano—Potential collapse and tsunami at La Palma, Canary Islands, Geophysical Research Letters, 2001. DOI: 10.1029/2001GL013110

Related content:

Subscribe to our newsletter

The latest news from Science Norway, sent twice a week and completely free.