How Norwegians became ocean bathers

Holidays on the coast are now the most popular vacation form in Norway. But Norwegians were late among Europeans to adopt a liking for saltwater, the cries of seagulls and tanned skin.

Denne artikkelen er over ti år gammel og kan inneholde utdatert informasjon.

Norwegians have navigated and fished in the ocean for millennia before they built the first Viking ships. They were at home on the water, not in the water.

The sea was considered frightening and mysterious, linked to deaths and accidents. In the course of the 19th century saltwater and fresh ocean breezes became associated with good health and disease prevention.

Coastal sanatoriums and spas were established.

Started in England

The history of coastal tourism began with the English aristocracy and upper class, as they started flocking to ocean spas. Boarding houses and hotels thrived in holiday towns like Blackpool and Brighton. Eventually bathing opportunities became available and popular with the middle and working classes too.

The notion of vacationing on the beach gradually spread across the Canal to the Continent – to France, the Netherlands and Germany.

“We didn’t have much nobility or a sizeable upper class in Scandinavia. That, along with our peripheral position on the map, contributed to a later start here for the combination of bathing and tourism than in England and the Continent,” says Historian Berit Eide Johnsen at Agder University College.

She has studied research on tourism in Scandinavia – carried out in the form of anthologies, magazine articles and monographs from 1980 to 2010.

A refreshing bath

The upper classes in Sweden and Denmark were much wealthier and larger than their Norwegian counterpart. They were also more strongly influenced by European culture.

The proximity to Germany probably explains why what was probably the first Scandinavian bathing spa hotel was opened in 1819 on the North Frisian island of Føhr, which is now German, but was then Danish, explains Eide Johnsen.

As time passed, boarding houses also appeared on Denmark’s Zealand and Jutland. Artists and the urban bourgeoisie started frequenting these spots later in the 1800s.

They were inspired by the big change in attitude toward the sea that occurred in Europe, as it started to be viewed as a cure for various ailments and a general booster of health, for body and mind.

“But people were still not shedding clothes and sunning their bodies. After a refreshing bath the guests would get dressed and retreat back to the boarding house,” says the historian.

Sweden already had a bathing spa tradition, for instance at Varberg in Halland County and Gustafsberg in Bohuslän County.

Vacation started in Moss

Coastal tourism came later in Norway.

Moss Badeindretning [Bathing Facilities] and Sandefjord Kurbad [Spa] were both established in the 1830s.

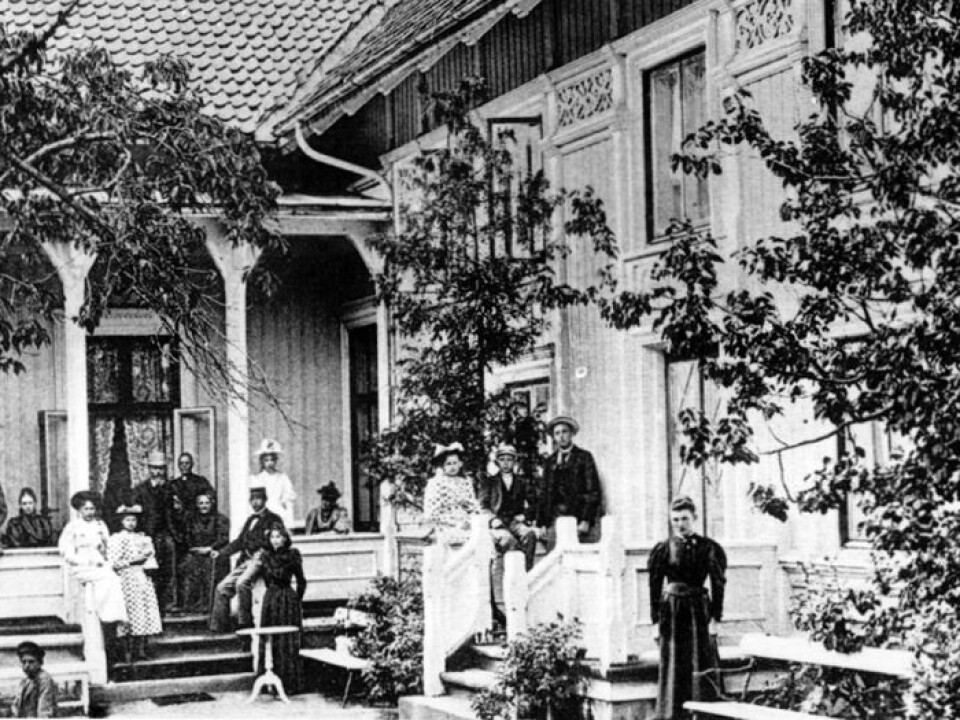

The first bathers came to Norway’s Hvaler Islands by Norwegian-Swedish coastal border in the 1860s. After a while the well-heeled started building summer homes by the sea and the first bath houses were opened.

Southern Norway discovered in mid-war years

Much later, in the years between WWI and WWII, bathers started to head for the southwest part of Norway – in Norwegian called Sørlandet. This is now the most popular vacation region in Norway for anyone seeking to swim and bask in the domestic sunshine.

The maritime trade, which had trafficked Sørlandet with sloops and schooners in the 1800s, stopped being a small town affair and became one of Norway’s major international businesses. This cleared the coast and picturesque coastal villages for an onslaught of tourists.

This was also the time when suntans became sexy. Tanned flesh came to Norway and Scandinavia via glossy magazine photos from the USA and the French Riviera.

This is was the golden age for boarding houses.

“Tourism became an important second income for many. Families often moved out of their homes in the summer and rented them to paying guests, who would return year after year.

Mothers and children often spent several weeks of the summer at boarding houses while their husbands, often with job titles like general manager, doctor or lawyer, would visit on weekends.

Boarding house culture disappears

But in the 1960s and 1970s such guest houses started to lose business and fold.

“There were a number of reasons. Some boarding houses had to close because of new, stricter fire regulations. But another factor was that people were becoming better off and demanded more comfort. Many of the boarding houses lacked indoor plumbing and toilets,” says Eide Johnsen.

She adds that vacations started having destinations further south, than Southern Norway – like other Scandinavians they started to head to Syden [The South], their general term for holiday destinations such as the Mediterranean countries and the Canary Islands.

People also started building their own cabins by the sea.

Vacations for the few

Coastal tourism became popular in England much earlier than in Scandinavia not only because Great Britain had a larger wealthy population. The industrial revolution created quite early a division between working hours and leisure time.

The burgeoning British middle and working classes got shorter working hours and more leisure time in the 1800s than their contemporaries elsewhere in Europe. In the 1900s a mounting number started to receive paid vacations.

Just a century ago – in 1914 – only about 20 percent of union member workers in Norway had vacation agreements.

The Civil Service Act was passed in 1918. It gave public servants a minimum of 14 days of holiday per year. But in most factories workers only received four days of vacation. A year later they got a whole week. By 1937 most workers in Norwegian industry had earned the right to 12 days of holiday per year. This amounted to two weeks then because Saturdays were also workdays.

Now quite a few Norwegians have cabins in the mountains as well as on the coast, even though they also fly to warmer countries to ensure hot sun and warm beaches. With so many places to cover, they need five weeks of vacation – which all are now guaranteed by law.

Translated by: Glenn Ostling