Chefs recreated 200-year-old dishes: “Surprisingly good”

In Norway, women from wealthy families prepared their own meals. This was not the case in other countries in the 19th century.

65 people sit eagerly, waiting for food from the 1800s.

The occasion is the launch of a cookbook containing 200-year-old recipes. This evening, some of these dishes have been recreated by chef Heidi Bjerkan from Credo, the café at the National Library in Oslo.

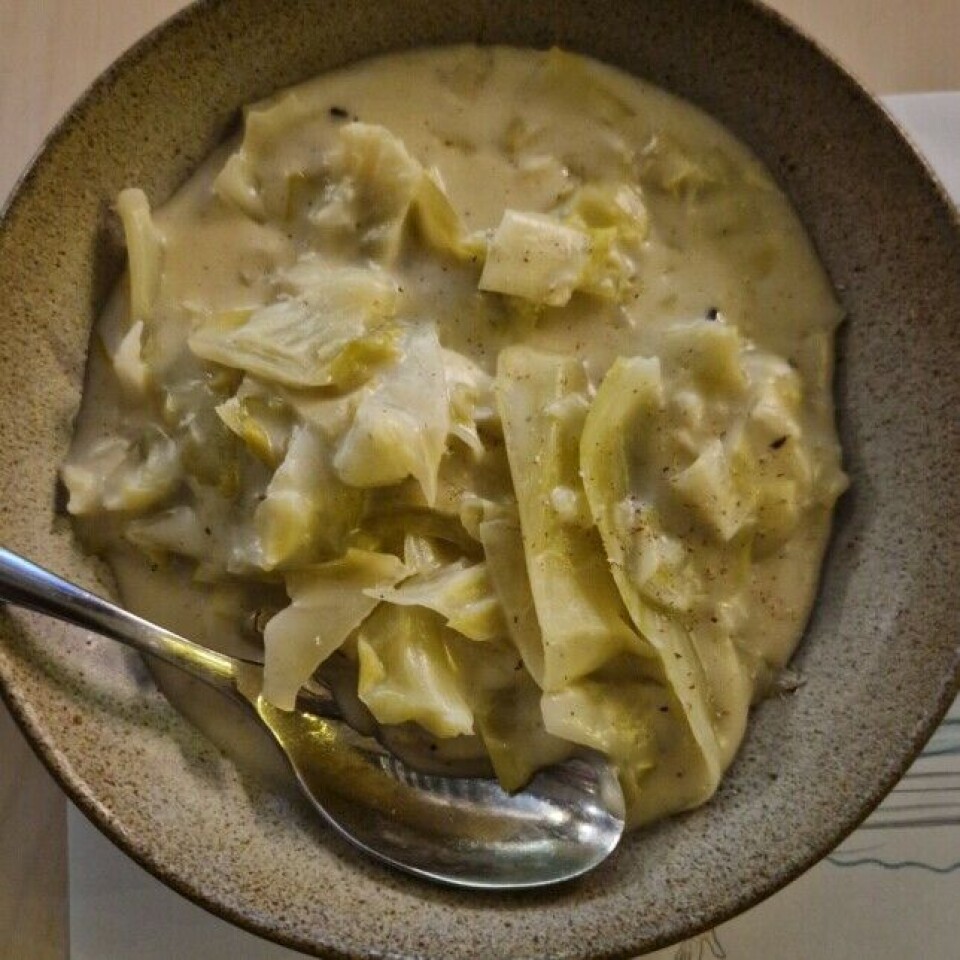

First up is the soup.

“Soup was always served first. They made broth from leftovers, because all food had to be used,” says Ragnhild Hutchison.

She is a historian and the author of the cookbook På borgerskapets bord. Mat, kultur og oppskrifter 1790-1830 (At the bourgeois table. Food, culture, and recipes 1790-1830).

“We have followed the old recipes but had to make some interpretations. The recipes state which spices to use but not how much,” Bjerkan tells sciencenorway.no.

“Recipes from the past are the closest we get to a time machine. We can’t experience the past, but by cooking the food they ate, we can taste it,” says Hutchinson.

In 1801, the population of Norway was around 880,000 people. There were only about 10,000 residents in the capital, Christiania. Most were poor. Only a few families belonged to the bourgeoisie.

These were families where the men were involved in trade both at home and abroad.

Hutchinson’s cookbook contains recipes from three women of the bourgeoisie. She also provides insight into the society surrounding food.

Patriotic food

Today, we talk about local food, bit back then, it was called patriotic food, according to the historian.

“Leading public debaters at the time strongly advocated for supporting Norwegian farmers and businesses by using Norwegian products,” says Hutchison.

That did not stop trade with foreign countries, nor did high tariffs on imported goods.

From the mid-18th century, there was great growth in foreign trade. Exports of Norwegian timber, fish, and metals increased sharply, while prices for many foreign goods fell.

The bourgeoisie were at the centre of this trade.

“New goods were constantly arriving in Norway, and they first reached the merchants' wives, who experimented with dishes from Paris, Amsterdam, and London,” says Hutchison.

“Wealthy farmers also brought home lemons, almonds, and coffee when they visited the cities, but these foods were primarily for the rich. Most people who lived in the cities were poor and had little opportunity to buy imported goods for a long time,” she says.

Focus on pure flavours

“New ingredients and dishes first became trendy among the bourgeoisie before slowly spreading across the country and becoming part of Norwegian food culture,” says Hutchison.

She compares it to the arrival of sushi in Norway.

Most viewed

“You had to be quite a hipster to enjoy sushi at first, but taste is just as much in your head as it is on your tongue. Trying new things gives you social status,” she explains.

Hutchison reminds us that taste changes over time.

“Good taste in the 16th and 17th centuries meant piling on the food to show wealth. But when more people gained access to sugar and spices, this changed. By the 19th century, status came from knowing how to use new ingredients correctly,” she says.

This shift made moderation in spice use fashionable, with a greater emphasis on pure flavours.

Additionally, frugality became a valued virtue.

“There was a deep concern for farmers, and excessive consumption was discouraged as part of a moral upbringing,” says Hutchison.

The king introduced restrictions: farmers were not allowed to serve more than four courses, and both wine and coffee were forbidden for them. Those who broke the rules faced fines.

“The bourgeoisie were allowed eight-course meals with four desserts. For the nobility and the royal court, there were no restrictions,” says Hutchison.

Mothers helped their daughters marry well

“Working on this cookbook made it clear to me how actively women participated in all parts of society. The women of the bourgeoisie weren’t just sitting at home twiddling their thumbs,” says Hutchison.

The Scottish journalist and travel writer Henry David Inglis visited Norway in the early 1600s. He was surprised that Norwegian women in the bourgeoisie cooked their own meals. Back home in Scotland, women from wealthy families would never work in the kitchen.

It was important for these families that their daughters married well. Their mothers taught them how to cook, shop for ingredients, and manage a household. This gave them a great advantage in the marriage market.

“It was demanding. Fruit and vegetables arrived in the summer and autumn and had to be pickled. Livestock was slaughtered in late autumn, with the meat dried and salted to last through the winter. Supplies from abroad were unreliable and could be stopped by weather, war, and pirates,” says Hutchison.

Inglis also noted that Norwegian bourgeois women lagged behind their French and English counterparts when it came to education, music, and literature. hey could not hold interesting conversations about anything other than food, he wrote.

Dinner at 1 pm

In the 19th century, dinner was served at 1 pm and lasted for many hours.

At 9 pm, people ate a late supper, with a variation of the same dishes from dinner.

The women of the bourgeoisie ran the kitchen, while maids cleaned and tidied the house.

“The maids often came from small farms and homesteads, where the food was completely different from what was served in bourgeois homes. They were not familiar with the dishes, ingredients, or the kitchen equipment,” says Hutchison.

Housewives also feared that their servants might steal from them.

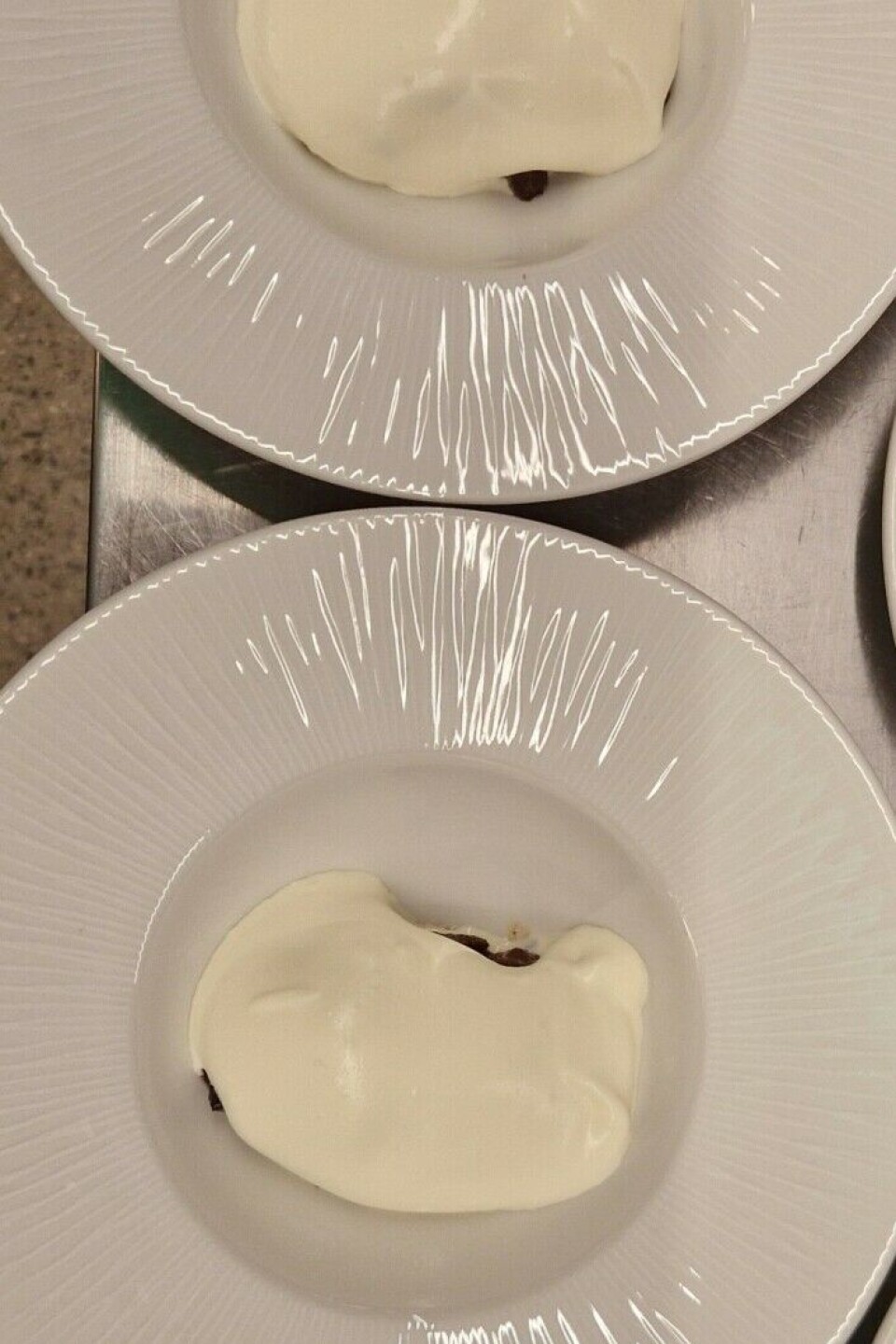

For dessert, guests enjoyed boiled pears, prune compote, whipped cream, and brown macaroons.

“The pears were lovely, and prunes are good at the end of a heavy meal. They speed up digestion,” says Hutchison.

“In the 19th century, many people complained of digestive problems, from constipation to diarrhoea. Prunes were believed to help,” she says.

———

Translated by Nancy Bazilchuk

Read the Norwegian version of this article on forskning.no

Subscribe to our newsletter

The latest news from Science Norway, sent twice a week and completely free.