The hunt for a shell with a left-hand twist

One summer long ago, two children found a naked hermit crab. They wanted to save it. But it would prove to be difficult. Decades later, sciencenorway.no is trying to figure out why the crab was in such dire straits.

“Hello, is this sciencenorway.no?”

The voice on the phone belongs to an older man. He introduces himself as Bjørn Skauge, and says he has a story we just have to hear.

The reason he has called is because of a recent article about the English snail Jeremy, who lived in a shell with a spiral that was anti-clockwise — or the opposite of virtually all other snails. The British scientists initiated a worldwide search to find a mate that had a shell with a spiral that twisted to the left, like Jeremy himself.

Skauge says he has a real story that is similar.

It is admittedly much older and a bit more local. But it touches on just as many deep questions in biology.

A poor naked hermit crab

Skauge says the whole incident was so special that he simply had to write a children's story about it. You can read the whole story in Norwegian here.

It began as a very ordinary summer day at the fishing village Myken in Nordland county, just above the Arctic Circle.

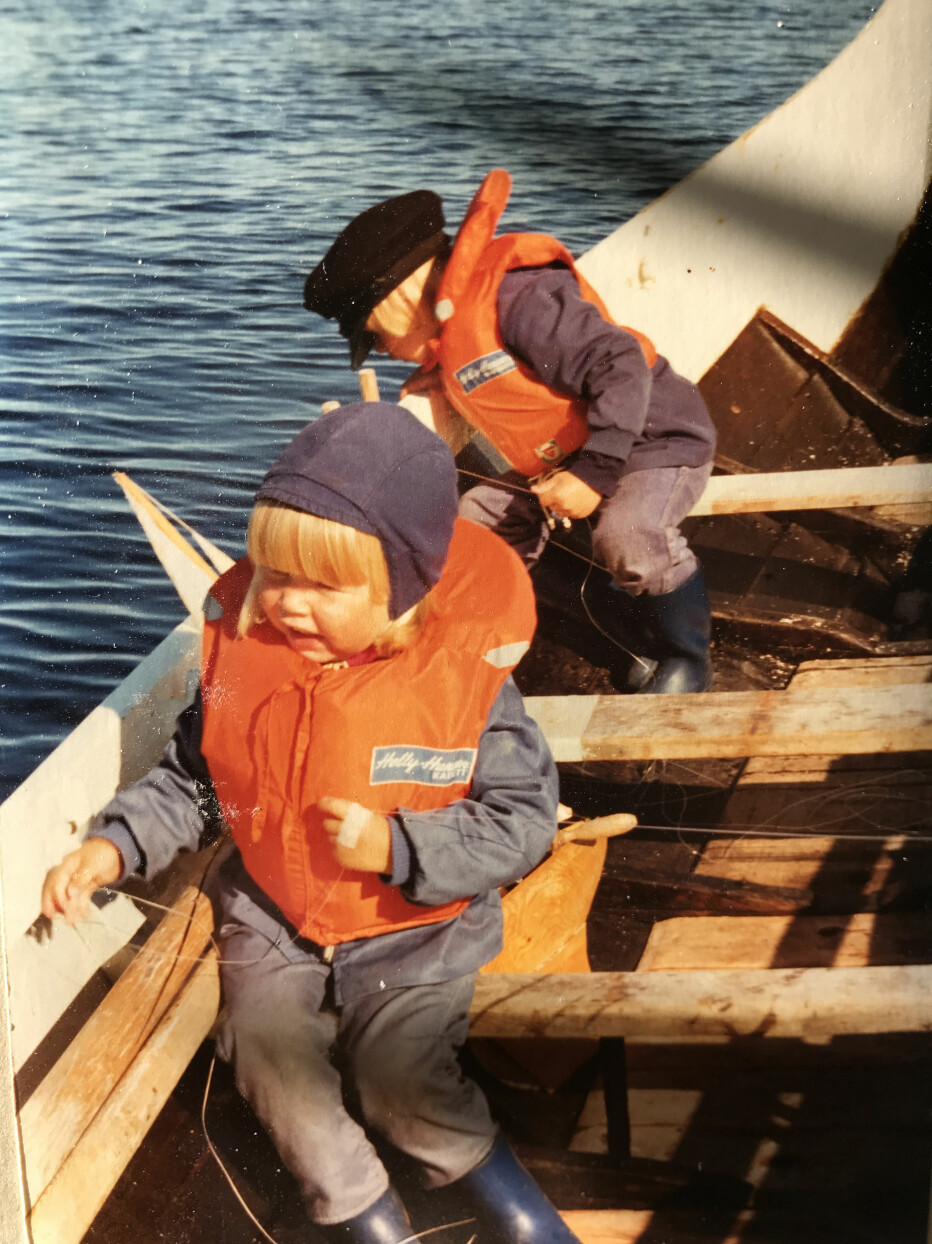

Skauge and his kids went for a swim. The ocean bottom buzzed with life. But then the children discovered that one of the little creatures on the bottom was a little different. It was a small hermit crab.

These small crustaceans usually use abandoned sea shells as homes. They don’t grow their own shell, but the abandoned sea shells offer them plenty of protection. As the hermit crab grows, it simply shifts to new, larger shells.

But this little guy had no shell. It was completely naked.

The kids were worried. Without a shell, a hermit crab can be easy prey for predatory fish. The children carefully caught it and took it to a tidepool on the shoreline. The plan was to find a nice new shell that the hermit crab could move into.

This would prove to be more difficult than expected.

Twisted the wrong way

The children gathered handfuls of shells. They offered the hermit crab one shell after another. And the little animal tried. It backed into the shells. But then it stopped and quickly rejected them.

That's when papa Skauge thought of something. He had been educated as a wooden boat builder and knew that the wood in tree trunks often twisted in a spiral. Interestingly, the spiral goes the same way in almost all species. But not always. Some trees twist the opposite way.

Could this be the case with the hermit crab as well?

After all, hermit crabs are lopsided. One claw is larger than the other, and the torso is twisted in a spiral to one side. Everything to fit perfectly in a shell.

But what if exactly this poor hermit crab was twisted the wrong way?

Most of the shells on the shoreline spiral to the right. Perhaps the hermit crab simply needed a shell that spiralled to the left?

A miracle

Now everyone, old and young, got involved in a large-scale hunt. Could they find a shell with a left-hand spiral, among all the sea shells on the beach?

It took a long time, but eventually they succeeded. Everyone was excited. The kids gently dropped the rare left-hand shell in the water with the naked hermit crab.

And a miracle happened!

The little critter moved in and walked away, happy with its new house.

Born like that or became like that?

Today those kids have long since become adults. But the questions from that summer day on Myken remain unanswered:

Why was the hermit crab twisted the wrong way?

Was it born that way? Or had it just accidentally chosen a rare, left-spiralled shell as its first residence, and consequently grew with a left-hand twist?

Is it common for hermit crabs to have a left-hand twist?

And not least: Did the kids save that little hermit crab long ago?

Sciencenorway.no contacted experts to find answers to these old questions.

The ocean’s lopsided creations

The first request went to Angus Davison, the researcher behind the studies of Jeremy, the snail with the left-hand spiral.

But Davison said that he didn’t know enough about hermit crabs to give us good answers.

However, Professor Henrik Glenner at the Department of Biosciences at the University of Bergen was willing to try.

“These are super exciting questions,” he wrote in an email to sciencenorway.no.

Glenner says that the hermit crab is not the only lopsided creature in the ocean.

For example, flounders lie with one side to the bottom, and the eye from that side wanders up over to the other side of the fish. That’s how a flounder ends up with both eyes facing up, even though one eye was once actually on the bottom side.

Lobsters and crabs are also asymmetrical. They often have a large crushing claw and a smaller cutting claw.

Glenner says researchers have conducted studies to figure out how this asymmetry happens.

Genes and environment

“Most flounder species have a species-specific side that is their ‘down’ side. For example, European flounders almost always have eyes on their right side,” he wrote.

But in a few species, there is an equal chance of ending up with the left or right side as the “down” side.

“Everything suggests that both asymmetry — eyes on one side — and whether the eyes are on the left or right side — are genetically determined in European flounder,” Glenner wrote.

In the case of the lobster's claws, however, the situation is different.

There is a fifty-fifty chance that the right or left claw will become the crushing claw.

“It is simply a question of which claw the lobster uses first, after it has settled on the ocean floor. That is, the question of which claw will be bigger is determined by factors in the environment — not by genes,” Glenner wrote.

But what about the hermit crab, then? Is it born that way or has it become that way?

The answer is probably: Both.

Inherited, with modifications

Several studies have been done on the rear part of the hermit crab's body, Glenner says.

“These studies suggest that a hermit crab already has an asymmetrical tail when it first lands on the bottom, and goes in search of a protective sea shell,” he said.

“Then the tail becomes more and more asymmetrical with each shell change, and the animal’s body increasingly fits better into a right-hand sea shell.”

If a hermit crab, on the other hand, doesn’t find a spiralled shell to adopt, it will constantly change its shell, but its hindquarters will become more and more symmetrical — which is different than hermit crabs that have found a spiralled mollusc shell.

“This means that an asymmetric tail is genetically determined, as in the flounder, but is modified by the environment, as in the lobster,” Glenner said.

Probably saved the hermit crab

“In Norway, almost all marine snail shells are right-handed. That's why most young hermit crabs have a right-spiralled hindquarters, which they can then modify,” Glenner says.

But there is no doubt that there are also young hermit crabs that basically have left-spiralled hindquarters.

They probably don’t have an easy life. Finding a suitable shell is more difficult. Some may be lucky and find a rare left-spiralled shell. But as soon as it grows out of this particular sea shell, it is in trouble again.

"That's why I definitely think those kids saved that hermit crab," Glenner wrote.

Spawned lifelong interest

People changed the life of the little left-spiralled hermit crab on that summer day on the Myken seashore.

But that little creature also changed people.

“That's where my interest in marine life was first piqued,” Christian Skauge said to sciencenorway.no. He is the son of Bjørn Skauge, and one of the children in the story.

“It occurred to me that there were so many strange and exciting things down there, and that there were still mysteries to solve,” he said.

His fascination for the sea never faded.

Today, Christian Skauge is a marine biology instructor with the Norwegian Diving Association and editor of the Norwegian magazine Dykking (Diving). He even printed his father's children's story in the magazine. And as an instructor, he occasionally brings up the story of the little naked hermit crab he found on the shoreline.

“It happens that I’ll tell people my story if they wonder how I got so interested in marine biology,” he says.

Translated by Nancy Bazilchuk

———