Does Norway need a new legal definition of rape?

In Norway and Europe, activists are fighting to change rape laws so that rape is defined as sex without consent. Researchers say this won’t help much to change or solve the problem.

Two things have happened over the last 40 years in terms of rape and justice:

More and more cases are being investigated.

And a lot of changes have been made to the relevant legislation.

But the prosecuted cases are few relative to how many cases get investigated. And of the cases that go to court, fewer still are convicted of rape than other types of criminal acts.

Outdated and dangerous?

This year Professor May-Len Skilbrei welcomed her crop of new criminology students to the start of their studies with the seminar Rape in the courts: Is a new definition what’s needed?

Current Norwegian legislation defines rape as obtaining sexual activity by means of violence or threats, or with someone who is unconscious or for other reasons unable to resist. Using violence or threatening behaviour to make a person engage in sexual activity with another person- or perform acts corresponding to sexual activity on himself/herself is also considered rape. The actual wording of the law translated into English is sexual assault, which according to Skilbrei is used as a synonym to rape.

Amnesty International is among the organizations that have called for a further change in the legislation in recent years – specifically, that rape be defined as sex without consent. In 2018, the organization claimed that several countries in Europe, including Norway, have dangerous and outdated rape laws because they do not include such a clause.

Amnesty believes that the law’s definition must explicitly state that sexual intercourse without consent is rape. The United Nations Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) has also criticized Norway because a consent requirement is not part of the Norwegian rape provision. Consent is a requirement of the Istanbul Convention, the Council of Europe Convention on preventing and combating violence against women and domestic violence. Norway ratified this convention in 2017, and must therefore comply with it.

The Norwegian non-profit Legal Aid for Women (JURK), is another organization that wants to see a consent clause in the Norwegian legislation. Representatives from JURK who spoke at the seminar claimed that a requirement for consent is present implicitly in the Norwegian legislation, but that there is a need for consent to be explicitly addressed.

Sweden introduced a consent clause in 2018. In Norway, the Socialist Left Party (SV) suggested that Norway should do the same but did not receive sufficient support in the Parliament.

The law can't do magic

“The closer you get to the law, the less you’ll believe that legislation can magically change the world,” says Ragnhild Hennum.

Hennum is a professor of public law in the University of Oslo’s Faculty of Law and has researched and written extensively on sexual violence.

“We all agree on the goal, these are undesirable actions that we would like to eliminate. But opinion differs on whether people think that the law is the best tool for changing people's behaviour. Those who argue for a change in the law say that it should send a signal, which I agree it should do. But is a provision in the penal code really the best way to send a signal to young people?

Hennum doesn't believe that a new definition will cause any great changes.

But she states that she’s not strongly against it either.

“I don't think it will do any harm, and maybe we could avoid critique from GREVIO, the body that oversees the implementation of the Istanbul Convention, when they come and monitor us. But I'd rather talk about other things that I think are more effective,” she says.

Law Professor Hennum and Criminology Professor Skilbrei are both involved in the newly launched research project Evidently Rape, which will research the medical, legal and lay understandings of physical evidence in rape cases. The project will follow the physical evidence from the point of collection to when this evidence is submitted to the court.

Dramatic increase in investigated cases, but not prosecution

According to figures from a large survey conducted by the Norwegian Centre for Violence and Traumatic Stress Studies launched in 2014, one in ten Norwegian women and one in 100 Norwegian men have been raped during their lifetimes. Only eleven per cent reported the incident.

However, the number of reported rapes has increased significantly over the last 40 years.

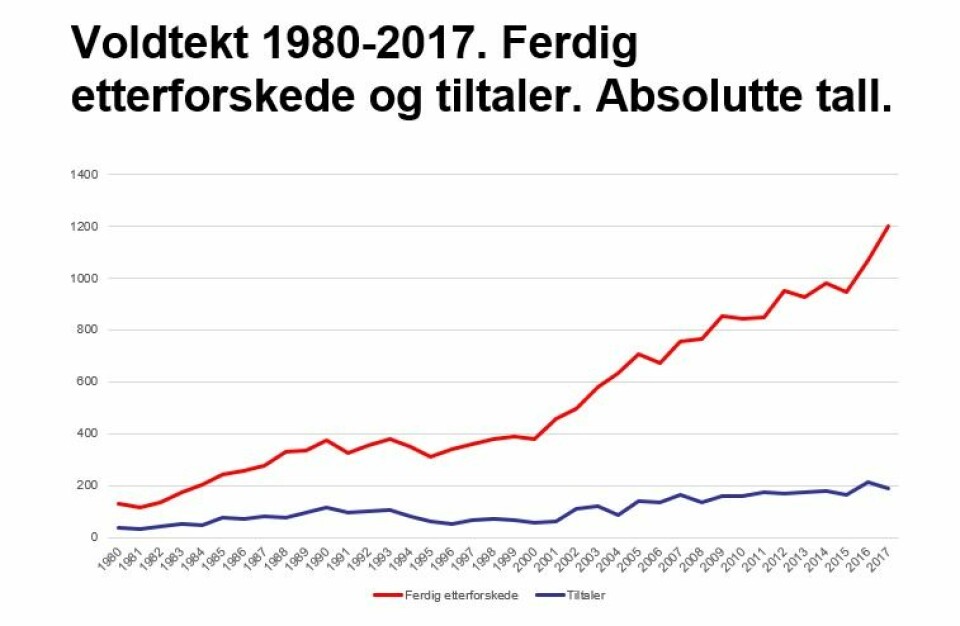

Hennum has compiled figures from 1980 to 2017, showing the number of cases investigated and the number of charges brought. Researchers in the field prefer to use the measure of the number of completed investigations rather than reported incidents, because those records extend farther back in time.

A charge is brought when the police believe that they can prove a rape has taken place and the prosecuting authority decides to bring the case to court.

The number of completed investigations has increased exponentially from 1980 to the present. The number of prosecutions has increased somewhat in actual figures, but has remained almost unchanged compared to the number of investigated cases.

“A large gap has opened up from 1980 to the present. The discrepancy between the two numbers is huge,” says Hennum.

The last year included in the graph, 2017, shows that 1201 cases were investigated. Only 186 of them ended up being prosecuted.

Changes in legislation and public conversation

The fact that so few charges are being brought relative to the investigated cases is part of an international trend, says Hennum. The number of reported cases is going up, but the charges aren’t following suit.

The increase in reported rapes can perhaps be explained by the fact that legislation has changed.

In 2000, a provision about engaging in sexual activity with someone who is unconscious or unable to resist was moved from one paragraph to another in the Norwegian Penal Code, so that these situations are now defined as rape. These rapes are difficult cases for the police, according to Hennum. Nearly 45 per cent of reported rapes in 2017 were what police call party-related rapes, according to figures from Kripos, the Norwegian Criminal Investigation Service.

“It’s difficult to determine exactly what’s happened when the perpetrator, the victim, and all the witnesses were drunk and no one remembers things clearly. Figuring out that sexual activity took place isn’t hard, but was it voluntary or not? The normal situation is that two people who enter a room at a party and have sex with each other do it voluntarily. Then the police have to pick out the cases where it wasn’t voluntary, and often they have no good evidence,” says Hennum.

Hennum also believes that we talk about rape in a different way today than we did 40 years ago. It doesn’t change the kind of evidence you can find in cases, but it can change the number of reported incidents.

Kripos likewise says that the increase in reporting may be due to greater openness about rape in society, but also the expectation that police are giving higher priority to rape cases.

Resources for police and talk to the youth

So what do you do with a problem like this, in the eyes of a seasoned law professor?

“A lot of work is done in vain in life,” says Hennum, pointing to the Official Norwegian Report NOU 2008: 4, Fra ord til handling: Bekjempelse av voldtekt krever handling (From words to action: Combating rape requires action).

“I sat on the committee that wrote that report,” she says. “The issue of consent wasn’t up for discussion then, but we discussed numerous measures that could be implemented. This report has been lying in a drawer, which I think has been locked, for 11 years.”

There’s little point in blaming the police, according to Hennum. “They’re doing the best they can with the resources they have. Those resources should be increased, and more prestige should be attached to dealing with rape cases.”

And then we need to talk more about rape.

“Criminology students may talk more about this, but I know how little we talk about rape in law school. It's not a big topic for us, just a paragraph among many that students have to learn,” she says.

And we need to be talking with adolescents, but this is only done to a small extent, and not systematically, according to Hennum.

Sexual legislation is constantly changing

“For criminologists and forensic sociologists, it’s particularly interesting to look at sexual legislation,” says Professor May-Len Skilbrei, who is herself a criminologist and sociologist.

“Historically, this is legislation that has changed a lot, and the section on sexual offences in the Penal Code is constantly changing. This has to do with how our views on sexuality and gender evolve and that the boundary between what is private and public is changing."

The last 40 years have seen dramatic changes in what is regulated by the Penal Code, according to the professor.

“Sexual legislation isn’t written in stone, because it’s an area of major societal change,” she says.

This kind of legislation is also interesting to study, because people often have high expectations to the law and the problems it should solve. And high expectations to sexuality.

“Sexuality is an area that is becoming more and more important for personal development and integrity. So the laws concerning it are also growing in importance,” says Skilbrei.

“The last 40 years have seen regular discussions of what should be included in this law. Lawyers have been discussing what to count as rape – anal penetration, artefacts – should they be included? So this whole chapter sort of clarifies what we understand as sex societally, and what society considers abusive when it comes to sex.

The law doesn’t reflect experience and feelings

Skilbrei does not believe that a consent clause will bring about the desired change, either.

“Will a new way of defining rape change the way police work? The way judges judge? Probably not. You are a lot of things we can do besides changing the Penal Code. It isn’t uncommon, once you start discussing changes to the law, for this to become the big solution instead of talking about all the other preventive possibilities that exist,” she says.

At the same time, it is true that law and justice are expressions of culture.

“The law can express a norm and can influence action in the long term. It might make it easier to communicate more clearly with youth. Laws can change society, not just because someone does or doesn’t do something, but because they change the way we as a society understand ourselves and others.”

But Skilbrei warns against tying the rape conversation to what is contained in the Penal Code.

“The law is technical, it is supposed to be distinct and to be used in court by lawyers and judges. It's not strange that it doesn't match people's experiences and emotional lives. The conversation about sexuality shouldn’t be limited to what is inside and outside the law,” she says.

Consent laws in other countries

Skilbrei followed the Swedish debate on the consent clause closely.

“In the debates leading up to the decision, you would have thought no other countries in the world had a consent law. Some people said how important it was for the world that Sweden adopt this, as if Sweden invented the consent law,” says Skilbrei.

She thinks it’s important to look at countries that have had consent-based legislation for a long time to learn from their experiences, and to adjust our expectations of such a law.

“England had a consent law 200 years ago, which doesn’t have us believing that rape was handled well then. And today, countries like India and many other former English colonies have consent laws, yet they have many examples of victims not being believed and of consent being considered difficult or impossible to prove. South Africa, for instance, has high rape figures despite having consent legislation. So it would seem that this legislative clause is not as directly preventive as some debaters want to assume,” Skilbrei says.

In addition, a lot of people believe that consent is part of the Norwegian rape legislation, even though it is not actually stated in the paragraph itself.

“Lawyers use interpretations provided in the preparatory work and in previous judgments to apply the law, so they explicitly look for signs of lack of consent to determine whether coercion has taken place. This is the case in many jurisdictions. The question is whether that is a problem or not,” she says.

Should everyone report?

Despite the low rate of prosecution and the fact that many rape cases do not win in court, activists have felt that it is important for rapes to be reported so that society understands the extent of the problem.

“We don't discuss this enough,” says Skilbrei. “We hear a lot of talk that everyone should report, and it can give the impression that reporting is what one should do and what is best for all parties. But what happens for the vast majority is that the case is just dropped. That may not be good for everyone to experience.”

Skilbrei notes the example of large Internet cases that police have uncovered in recent years, where a single case has often resulted in hundreds of potential victims being identified. In Kripos' latest report from 2017, these cases led to the introduction of a new statistical category, rape over the Internet.

“Here we have examples of people who initially didn’t feel offended, who were being contacted by the police and told that they’d been raped. What do you gain from seeing yourself as having been raped, or for others to see you as having been raped?” she asks.

Available surveys where victims and offenders were asked about how they experienced the trial provide very divergent answers. A trial is basically a conflict between society and a person who has committed a criminal offense, say both Hennum and Skilbrei.

“In light of this it's important to discuss the effect of more and more people considering themselves to have been raped. Do the interests of the state and the individual always coincide here? If we want to do something for the victims, it needs to be something other than going to court, which has a completely different purpose,” says Skilbrei.

Consent clause mirrors peoples understanding of rape

One of the organisations that think Norway needs a consent clause is JURK, Legal counselling for women.

During 2019, JURK has been on a nation wide tour to talk about rape in high schools.

"When we are out there at the schools and we ask the youth what they think rape is, they answer that is is involuntary sex. It's hard to go from this simple answer, to then explain what the law says", says Assia Chelagma from JURK.

"Implicitly, sex without consent is punishable by Norwegian law. But the law doesn't state this explicitly. This makes the law very difficult to use when you're giving information. A consent clause would much better mirror peoples' understanding of what constitutes rape."

JURK also believes a change in the legal definition will make it easier to prosecute cases, and that it will be easier for both victims and perpetrators to understand that what happened was rape.

"We don't make the Penal Code based on what we can investigate or not. The Penal Code should be about what we consider to be punishable by law", says Chelagma.

A decent argument

In case there should be any doubt, Ragnhild Hennum repeats that she and professor Skilbrei and the activists who want to change the law agree on the basics.

"You are easily interpreted as someone who thinks it's ok for rape to occur, if you ask questions about these sorts of things. Well we don't think rape is ok. What we are discussing here is what society should or shouldn't do about it."

JURKs argument about the law making it difficult for them to communicate with youth about rape is one of the best arguments for changing the law that Hennum has heard so far, she says.

The preparatory work for consent legislation in Iceland has supposedly only focussed on changing norms and attitudes toward rape - no hopes of more perpetrators being prosecuted. Hennum thinks this is the way to go about it, if the law is to be changed.

"I do not believe that a consent clause will lead to more prepetrators being convicted, the problems with evidence remain even if you change the law. So this does not solve the basic existing problems already present. But increasing our opportunities of explaining to people what is and is not legal, is important", says the law professor.

"But then I think, how many of you have actually read the Penal Code? The Penal Code is perhaps not the best mode of communication for this."

———

Read the Norwegian version of this article on forskning.no