People are deceived by Internet fraud daily. Police are often unable to help

“As long as 1 in 10,000 falls for the scam, it pays off for the criminal,” professor Petter Gottschalk says.

“There is a scale from the completely spontaneous and clumsy to the thoroughly planned that lasts for a long time before going on the attack,” Petter Gottschalk, professor at Norwegian Business School (BI), tells sciencenorway.no.

There are various methods of fraud used online. He tells us about business e-mail compromise, which is the scammers' most advanced method so far. They commit data breaches in order to keep up with e-mail exchanges over time.

“When you gradually understand the format a person uses in their communication, you can go in and adopt their role,” Gottschalk continues.

Essentially, the scammers pretend to be someone else.

“That was how Norfund was swindled out of 9 million NOK. It requires about a year of work from the criminals before they have the chance to strike,” he says.

The Norwegian state-owned development aid company Norfund was defrauded in 2020 (link in Norwegian).

“Not very professional”

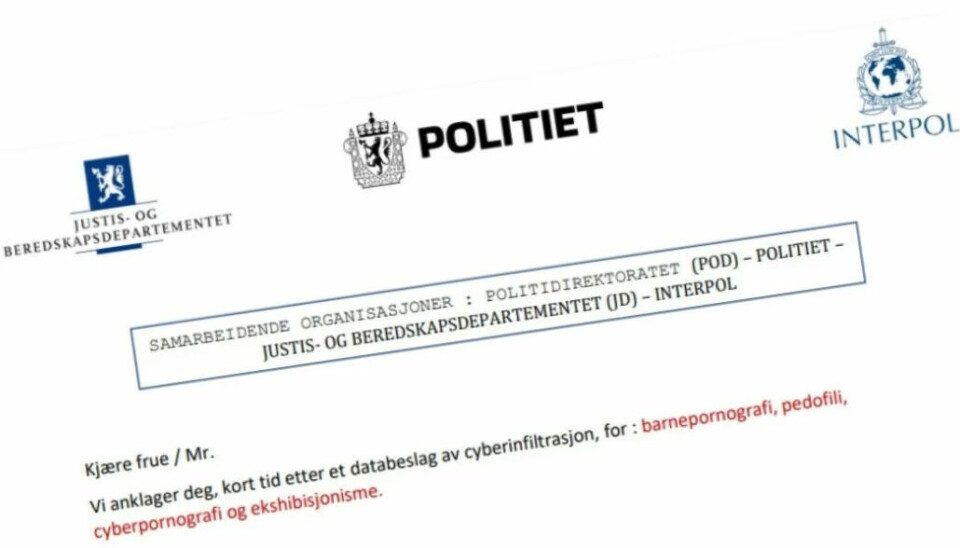

Lately, many have received the e-mail displayed at the top of this article. It may look like it’s from the police and accuses the recipient of being in possession of child pornography. However, there are a lot of aspects of the e-mail that don’t look quite right.

“My first impression is that this does not look very professional,” Andreas Lunde tells sciencenorway.no. He works as a communications adviser at the National Authority for Investigation and Prosecution of Economic and Environmental Crime (Økokrim).

This fake e-mail from the police has deficient language, as in this excerpt:

"For your information: The legislature has declared that the crimes and offenses provided for in the penal code, when committed through a telecommunications network, carry heavier penalties."

Gmail address

It is also somewhat suspicious that National Police Commissioner Benedicte Bjørnland operates with a Gmail address. But in other cases, such fraud attempts can look like completely genuine e-mails, he says.

“A serious problem is that when criminals sign their e-mails off with names of leaders in the police or use police symbols, it helps to undermine the trust afforded to police in society,” Lunde says.

In other cases, it may affect the Norwegian Tax Administration, Posten Norge (the Norwegian postal service) or banks. Some fraud attempts look fairly homemade. Others are tailored to the victim.

Organised crime

There may be major criminal activity behind the fake e-mail or phone call you receive.

“In these kinds of scams, you will commonly receive either e-mails or telephone calls where they pretend to be calling from the police or other public agencies, and we assume that it is often organised criminals who are behind,” Lunde says.

“They can make these calls from large call centres around the world. Their job is to raise as much money as possible by tricking people on the other end of the line. Whether the victims have to leave home as a result of the crime is rarely something that worries them,” he says.

Often, there are mass e-mail fraud campaigns. Some people can also be exposed to what is known as phishing.

“These are targeted campaigns where the swindlers have gathered information about the victim and put this in a context so that the e-mail appears credible to the recipient,” Lunde continues.

The information can be used to make the fraud attempt look more credible. Maybe your friend has sent you an e-mail asking for money because he's in trouble.

Nigerian inheritance

The Nordfund scam is of the type that Gottschalk calls tailor-made. The scam is tailored to a person, bank or company. On the other end you get more primitive mass mailings.

You might receive an e-mail from someone who has inherited money from his deceased cousin in Nigeria. It’s a hefty sum of 12 million US dollars, and the person in question needs help moving the money.

“As long as 1 in 10,000 falls for the scam, it pays off for the criminal. This type of fraud does not require any preparation,” Lunde says.

Gottschalk places the fake police letter at the same end of the scale as the Nigerian inheritance.

Impersonal and transparent

“The scam has been broadcast and they hope someone will take the bait. When you read it, you see that it is not adapted to the person at all,” says Gottschalk.

“Even though it seems quite brutal to be accused of paying for sex, partaking in fraud or other illegal activities, the language used is so bad that you should be able to deduce that this definitely does not apply to you,” he says.

The general population are not often exposed to any tailoring techniques. These are instead used where there are large amounts to be collected.

“Like in the Norfund case, who finance development projects in developing countries,” he says.

The fraudsters paid attention and waited until it was time for a transaction to Cambodia of NOK 9 million.

“And then they hijacked the transaction,” he says.

Swiss fraud?

Nigerian fraud is often talked about when suspicious e-mails arrive. Maybe Swiss fraud can work just as well and be just as justified.

“Switzerland is a strange country,” says Gottschalk.

By this he means that it is a democratic and regulated country, but that in business there is little control.

“This allows them to safely operate this type of fraud from Switzerland. The company might be registered as a computer company but they engage in fraud as a secret side business,” he says.

Those who only engage in fraud may live in more corrupt countries around the world.

Be sceptical!

Lunde encourages people to sceptical. But what should you do if you receive a questionable e-mail or phone call?

“If you can tell it’s a scam, just delete the e-mail. You have to be vigilant and sceptical of anyone who asks for money or personal information,” he says. “If you have been in contact with a scammer and they have succeeded in defrauding you, you must report it to the police.”

Too late when the money has left the country

Many have shared stories of how they were scammed. Even so, there are still many who fall for it.

“Økokrim is called daily by people who have lost their money,” Lunde says.

We are not always talking about large sums. They take what they can get.

And when the money is in the hands of the fraudster, it is often too late.

“The moment you have sent the money abroad it is unfortunately unlikely that you will see it again,” he says.

Investigating cyber fraud requires a vast amount of resources.

Prevention is key

“How do the police treat fake e-mails in which someone pretends to be the police?”

“The volume is so large that we cannot stop everyone. Those behind the scam could be sitting in call centres in Eastern Europe, India or Nigeria. Therefore the most important thing we can do is carry out preventative work,” Lunde answers.

He urges everyone to remind friends and family that online fraud is rampant.

“The police cannot reach everyone, so children and grandchildren can play an important role here. They can do this by telling their parents and grandparents that fraud actually happens – and that it can happen to anyone,” he says.

Lunde encourages everyone to end any conversations if personal information, passwords or PIN codes become a topic.

“Maybe it is also possible to practice this. The scammers are professional and cynical and will use every opportunity to turn the conversation into something that takes them one step closer to the information they are looking for,” he says.

“Not difficult to track”

“They are not difficult to track. But the Oslo police lack competency in this area. Some expertise can be found in the National Criminal Investigation Service (Kripos),” Gottschalk says.

He further explains that it is fairly easy to find out which machine the scammers have used.

“But you cannot prosecute a machine. So that's where it stops,” he says.

Gottschalk does not agree with Økokrim that preventive work is what works best.

“That’s just nonsense. The only preventative measure is to catch the criminals. The only reason for me not to drive too fast on the road is that I think there might be speed traps. The police send out some threat assessments and such, but they’re not helpful,” he believes.

Different methods in other countries

Gottschalk says that the system for catching criminals is different in other countries.

In the United States they have what is known as asset recovery, which will ensure that it does not pay to be a criminal – and that the victim gets their money back. You can read more about asset recovery on the EU's website.

“How will the police work in the future if the methods of fraud become more advanced?”

“Økokrim says that the criminals have become very advanced, but they actually haven’t. In the case of Norfund, it was human error. That the criminals have become ‘so advanced’ is something the police say to get more resources,” Petter Gottschalk believes.

———

Translated by Alette Bjordal Gjellesvik.

Read the Norwegian version of this article on forskning.no