Non-citizens punished by deportation

Norwegian police use deportation and punishment interchangeably to avoid spending resources on foreigners in prisons

Denne artikkelen er over ti år gammel og kan inneholde utdatert informasjon.

When immigrants in Norway commit petty crimes, they might face deportation rather than criminal charges, a new study shows.

University of Oslo criminology professor and project leader Katja Franko says research shows how “crimmigration, ” the mixing of criminal penalties and deportation, is increasingly becoming everyday practice in the police force.

In essence: Criminals are deported, and unwanted immigrants are treated as criminals.

Fewer legal rights

Deportation is not defined as punishment in the Norwegian legal system but is used that way in practice.

“This practice can have serious consequences. In criminal cases, you have the right to counsel and to remain silent. Deportees have no such rights. We are conscious of human rights when it comes to punishment, but much less so with deportation,” says Franko.

Cheaper to deport than to imprison

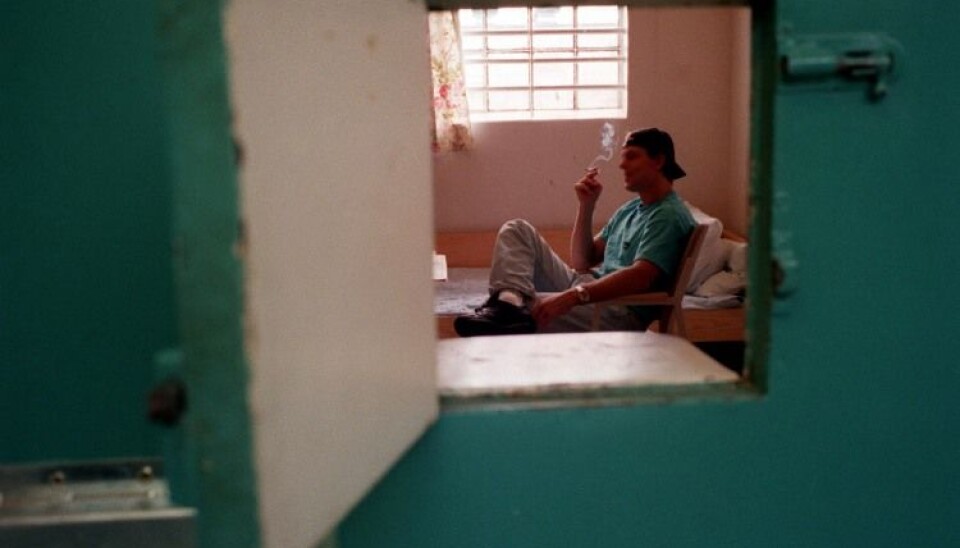

Norwegian jails are filling up with foreigners. One third of inmates and six of ten people held on remand were non-citizens in 2013. That costs money.

Researchers interviewed 64 Norwegian National Police Directorate (POD) and Ministry of Justice officers and employees.

Those who work with immigrants take a pragmatic approach. “The criminal justice route is a much lengthier process and cases can end up being very expensive,” says one Police Directorate employee. By using immigration law, foreigners can be deported for not having proper papers, rather than being tried for their suspected criminal activity.

Criminals cost billions

In a 2014 report, the POD looked closely at the crimes of 24 foreigners, finding that the average cost for criminal proceedings was over NOK 800 000 each. Extending this to the thousands of deported criminals comes to several billion kroner.

“There are good reasons to intensify efforts to return foreign criminals faster than we do today. It can save society huge sums, and it has a deterrent effect because these individuals are prevented from committing new crimes in Norway when they are deported,” POD Technical Director Atle Roll-Matthiesen told the Norwegian Broadcasting Corporation.

Deportation seen as extra punishment

Deportation cases have doubled in the last five years, from about 2500 cases in 2009 to more than 5000 in 2013.

Criminal proceedings were brought against only nine individuals of 500 arrested in an action against the open drug environment in Oslo. Most were deported. Expulsion can sting more than a conviction, and is often felt to be extra punishment after having served a sentence, according to Franko.

Authorities are using punishment to be able to deport EU citizens, especially Romanians, she says.

Pickpockets expelled

Foreign nationals made up over 95 per cent of pickpockets arrested in a police operation in Oslo. While people were previously fined and let go for this and other petty crimes, now they may be deported. The threshold for deportation has been lowered, Franko says.

The prescribed penalty for returning to Norway after being deported recently increased from six months to two years, which police see as an important tool to prevent the return of deportees.

Lacking high-level control

Practical considerations seem to carry more weight than judicial principles when deportation and punishment get mixed up.

“It surprised me that people working higher up in the system often aren’t aware of the scope of the issue. This development is primarily happening on the ground,” says Franko.

Still, politicians are noticing. “We are moving in the direction of using deportation as a means of preventing repeat offenders from coming back and committing serious crimes. I see police using this tool whenever they can, and I think we can expect it to happen more,” said Minister of Justice and Public Security Anders Anundsen in the Norwegian Parliament in December 2013.

Two legal systems

Franko is concerned that the choice between deportation and criminal justice has been a discretionary one, without a more fundamental discussion about the changes.

Franco believes that beyond the issue of individual legal rights, it’s important to apply the law the way it was intended: criminal law for crimes, and immigration law to control migration.

“As it is now, we’re creating a two-tiered criminal justice system, one for Norwegians and one for non-citizens,” she says.

The Ministry of Justice and Public Security had no comments to the research results when contacted by Norwegian science magazine forskning.no.

--------------------

Based on an article by Ida Kvittingen, which can be read in Norwegian at forskning.no

Translated by: Ingrid P. Nuse