Opinion:

The coronavirus pandemic has taught us something important: Technocrats are no longer precautionary

OPINION: In present-day Sweden, an expert – state epidemiologist Anders Tegnell – is de facto head of state. Tegnell has based his strategy on model projections rather than testing and tracing, and the venture is proving a spectacular failure, writes Emil Flatø

In present-day Sweden, an expert – state epidemiologist Anders Tegnell – is de facto head of state. At least when it comes to managing the coronavirus pandemic. The venture is proving a spectacular failure: Cumulative deaths per capita in Sweden are more than ten times higher than in Norway, and among the highest in the world. Reaching the top of the contagion curve has taken considerably longer. The economy is still suffering nonetheless. Swedes have also had to limit their freedom of movement, albeit more haphazardly.

The woeful irony is that it is not even likely that Sweden is that much more prepared for a second contagion. In Stockholm, the hardest-hit region, immunity in the population was recently estimated to 7.3 %. The proportion is significantly larger than in Oslo, but a far cry from the critical mass that can act as a natural buffer from a second viral outbreak.

Tegnell has stuck to his guns to the point of ridiculousness, but recently made a concession. “Had we encountered the same disease today, knowing what we do now, I think we would have landed on something between the Swedish approach and what the rest of the world has done,” he told the national broadcaster SVT’s flagship newshour, Eko. Mea minima culpa.

There is a lesson to be gleaned here, which should be elevated to the status of established truth, carved into the stone façades of powerful institutions, and enshrined in the constitution of any truly democratic nation: Politics needs to be deliberated by the plurality of actors that comprise a democracy, never by experts alone.

Computer simulation is at the heart of modern epidemiology, as is the case in many applied scientific fields. Models abstract reality into a system expressed in numbers, be it the global climate system or the networks enabling a local contagion to become a global pandemic. Scientists are often the first to point out the fallibility of models; at the same time, their use value is enticing. To paraphrase an article in the Norwegian Medical Association’s Journal, co-authored by the head of modeling at the Norwegian Institute of Public Health (NIPH), Birgitte de Blasio: Models are tools which allow us to calculate more consequences of pandemic measures than our mortal brains can compute themselves. In this crisis, they have not merely been used to gauge the consequences of measures, but also to estimate the severity of the virus and likely paths of contagion, often before empirical data were available.

Yet, in the running evaluation of the covid-19 response, some voices in the epidemiological community itself have begun to warn against the dangers and blind spots of relying too much on modeled information.

A quick comparison of the responses in different countries in the British Medical Journal revealed that the countries leaning too heavily on models, had less control over the spread. According to the authors, Devi Sridhar and Maimuna S. Majumder, a critical blind spot was the way that early models underestimated the need for testing and tracing. The countries which are currently being praised for their response – say, Germany, Norway and New-Zealand (which until recently had seen no cases for weeks) – share certain features in their crisis governance: Politicians make final decisions, and their leaders based their thinking on several sources of knowledge and advice. Where Sweden has a single Public Health Authority, the Norwegian public had to sift through the divergent advice of the Institute of Public Health and the Directorate of Health. In Germany, Angela Merkel could reap the rewards of a well-financed public university and research sector – she could seek advice from a far larger plurality of expert opinions.

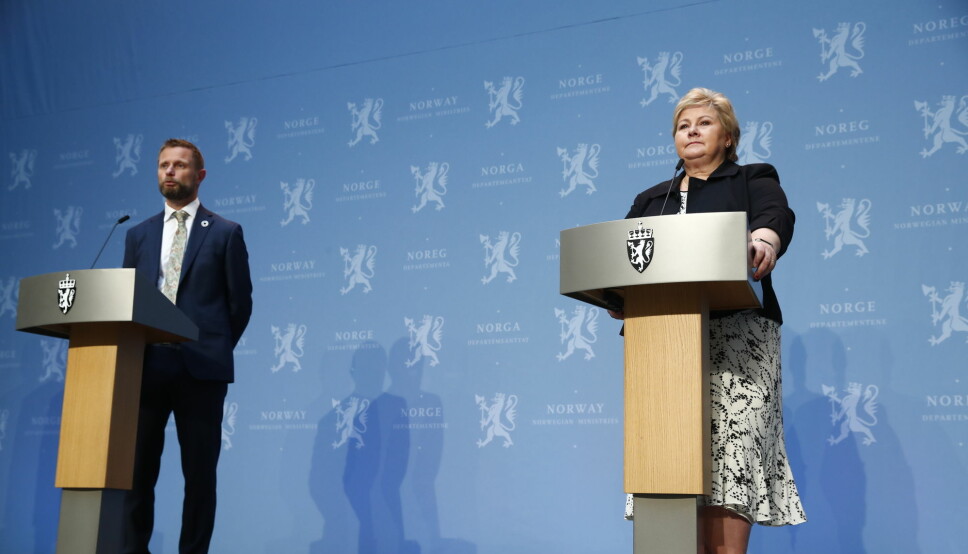

Throughout the spring, Camilla Stoltenberg, director of the Norwegian National Institute of Public Health, NIPH, has repeatedly critized the Norwegian government’s decision to close down schools, in direct contradiction of NIPH’s expert advice. It has felt like a breath-taking reckoning between the executive and advisory branch of government. Even if Norway sports a large research community for such a small population, a handful of research institutions with formal ties to government and critical advisory responsibilities – NIPH, Statistics Norway – tend to speak for whole fields of inquiry in the Norwegian public debate. In the press, Stoltenberg’s criticisms, and the discrepancy between the advice of two official expert institutions, has been treated as a weighty conflict. Erna Solberg, the prime minister, had to show up for an interview with the state broadcaster, NRK, insisting on her right to make final decisions:

“In certain areas, the government and the Directorate of Health have to make overall considerations that are not only about epidemiology, but about how the connections in our society work”, she said.

It seems that some of the same awe of the expert which has voices in the Swedish public accuse Tegnell’s critics as “disloyal” is in operation here. Yet, the Norwegian debate has been fundamentally contingent on the fact that decisions were made by the government. Stoltenberg’s criticisms have basically been about whether the lockdown was “nuanced” enough, especially the closure of schools and kindergartens. Had NIPH had similar decision-making powers to their sister organization in Sweden, they might have been defending what they recommended in March right about now: A more nimble mitigation strategy, more in line with the Swedes. If the Norwegian government had not had two expert reports on their hands, it is unlikely they would have had the necessary cover to act resolutely.

Back in NRK’s news studio, the prime minister shared a different, more conceptual, reflection. She emphasized how the government had been forced to act in due time. What conclusions were offered “in retrospect” was inessential to her. The remark gets at a matter which has become truly tricky in the encounter between elected officials and experts: Different perceptions of time in politics and science.

- Related: Norwegian health official: "We don’t think it's possible to stop the COVID-19 epidemic"

- Related: Norwegian government: "The goal is to beat the coronavirus epidemic as much as possible"

Science studies have repeatedly shown a tendency for scientists to neglect the epistemological implications of their methods – either for a lack of ability or interest. This problem has been exacerbated with the rise of computerized, big science.

One significant consequence is that technocratic rhetorics tend to be out of date with respect to the actual daily practice of scientists. “What’s the evidence?”, the technocrat asks, but model simulations are not evidence in a traditional sense. Models simulate reality –sometimes they even simulate futures, possible realities that are not yet. As such, they cannot produce “facts” or “data” either – those words build on past tenses of latin verbs, referring to what is done or what is given. In other words, they belong to the issue’s established “realities”, where models aim to capture the issue’s simulated and possible “virtualities”.

Don’t get me wrong, some findings from the unreal world of models have proven indispensable. A greenhouse effect caused by human emissions was a possibility in the numbers at least a hundred years before anthropogenic climate change materialized as serious disruptions. However, the most important simulated insights are usually either fairly general, or about the imminent future of predictable systems. Tomorrow’s weather report is a point in case.

The tricky issue, as prime minister Erna Solberg intimated, is what difference your knowledge makes when it matters. For the prime minister, there was little doubt about when it was time to act: Around those days in March. The question for her is what was known then. What was done. What advice was given. In the interview with NRK, Solberg made it clear that the government prioritized the immediate time horizon. The cabinet agreed to apply the precautionary principle, which to them meant to prepare for the worst-case scenario. They took an activist approach to the uncertainty about whether it was possible to suppress the contagion, and whether the spread could be managed through testing and tracing: It was worth a shot.

By contrast, the relationship between time in the physical world and time in the models is fundamentally ambiguous. When, exactly, is the time to act in the models? To even produce a simulation, you need to presuppose what time measures are introduced, before you can begin to calculate their plausible effects. Simply performing the analysis takes time. The model simulation from Imperial College published on March 16th – the study that made the rounds in several countries, informed a turnaround of the British strategy and deeply influenced Norwegian expert reasoning – only became possible a few days before publication, when the team got access to empirical data from China and Italy which they could use to calibrate. They simulated the effects of measures introduced in “late March”. Two weeks is a long time when a virus is spreading exponentially. Between March 13th and 27th, the number of cases in the United Kingdom grew from 798 to 14 543. More recently, the professor leading the study, Neil Ferguson, told the British Parliament’s Committee on Science that 20 000 lives would have been spared, if the country had locked down a week earlier.

That form of argument seems like a modeler’s trademark. It pops up in public remarks by Anders Tegnell and Camilla Stoltenberg as well: If we had known what we do today, if our advice had been listened to, et cetera. The arguments add a layer of temporal confusion, because they seek to build hindsight on what is actually counterfactual reasoning.

Politicians hurl counterfactuals at each other all the time, but they also know it rarely sticks, because counterfactuals cannot really be proven nor disproven. In the conversation informed by models, however, realities and possibilities live side by side in the constant search for valuable insight. One of the reasons there is so much retrospection and reflection in the epidemiological field at this point, even in countries where the epidemic is under control, is that the models are being calibrated for a possible second wave, or for different epidemics in the future. Until empirical data was available about SARS-Cov-II, observations of former epidemics, especially the swine flu outbreak in 2009, informed the modelled view.

The result is a veritable hodgepodge of past experience, future horizons and presence.

Try to keep all those thoughts in your head at once, when a phone call arrives from above, informing you that you have an hour to conclude about what measures to take.

A key concern when the epidemic broke out in Scandinavia in March, was how to deal with the uncertainties about the key statistical features of the new virus: How deadly was it? How contagious? How widely had it already spread? On this issue, it made a significant difference whether experts based themselves on modelled projections based on key indicators and former experience, or whether they recommended testing and tracing as much as humanly possible, in order to acquire concrete, empirical data.

The countries that are doing best today, chose the latter. Tegnell, on the other hand, seemed almost obsessed with what stage Sweden was at “on the curve”, arguing that testing was futile in the phase he believed they had entered, based on the contagion he thought he saw. Consequently, few efforts were made to map out where the virus was spreading as clearly as possible.

The question is not whether Tegnell’s conviction was right or wrong at the time. The question is when he had enough certainty in his indications and simulated insight to make fateful decisions.

After all, what was the harm in trying?

It appears something has changed in technocratic political culture.

Climate science was one of the first fields where long-term model runs were presented as basis for political advice, as a leap in the sophistication of climate modeling occurred in the course of the 1970s. It was a time when there was still serious debates about global cooling, and the estimates about the severity of anthropogenic climate change varied wildly. The uncertainty was overwhelming, but at the same time, it was recognized how much was at stake politically. The young climate modeler Stephen Schneider dedicated a whole book to the dilemma. He concluded that it might prove catastrophic to wait for perfect knowledge before cutting emissions. There were also more stoic voices, but the approach Schneider adopted became central to climate governance. It is currently known as the precautionary principle.

Climate change was a distant, if catastrophic possibility in 1976. The analogies only go so far as we are dealing with a pandemic requiring immediate action in 2020. A striking difference, nonetheless, is that this time, politicians – or the successful ones at least – were the ones to prepare for the worst and do all they could to suppress the contagion. On the other hands, respected experts advocated giving priority to uncertain, long-term possibilities. Early models advised against suppression, because of the danger of a more severe second outbreak. What is more, epidemiological models were the foundation for the conclusions of other experts: In Norway, the first governmental expert report about the economic consequences of the corona measures, led by Steinar Holden, was based on NIPH’s simulations of how a mitigation and suppress strategy would play out in Norway. This left the impression that there was a real choice between saving lives and limiting the economic cost for society. Subsequently, this estimation has been walked back considerably.

The guiding philosophy, it seems, is that our science has become so sophisticated that it is able to weigh immediate threats to people’s lives against more potential threats, without being overwhelmed by uncertainty.

In Sweden, a natural experiment is being conducted where that idea is in power.

———

Share your science or have an opinion in the Researchers' zone

The ScienceNorway Researchers' zone consists of opinions, blogs and popular science pieces written by researchers and scientists from or based in Norway. Want to contribute? Send us an email!