People who experienced war want reconciliation – but their children remain bitter

When the past is difficult, politicians use it to advance their cause. Now researchers have found that people who have not experienced a conflict are more bitter than those who have gone through it.

Kenneth Andresen was once a NATO press officer in Kosovo. Since then, he has continued to work on topics of war, crisis and the media and is now a lecturer at the University of Agder (UiA).

“There’s a focus on the past. The history of conflict is being actively used, and it’s happening more and more,” says Andresen.

Andresen and UiA colleague Abit Hoxha, along with researchers and mediators from ten EU countries, have been researching how European societies handle a difficult past. The project has been named Repast. Now Andresen is developing computer games and other digital solutions to convey Norway's difficult history.

Different versions

“Politicians play on historical memory a lot, and journalists often use it. They tend to refer to different versions of the story,” says Andresen.

He has conducted interviews in Bosnia and Kosovo and seen how the story versions vary, depending on which ethnic group the interviewees belong to.

“An important finding in the project is that history is being used more and more actively to promote various issues,” Andresen says.

He believes the most surprising result in the Repast project is how people who have been through a conflict approach reconciliation.

“People who have lived through conflict settle up with history and reconcile with it. They’re much more open to dialogue than people who’ve heard about the conflict after the fact. People who’ve only been told about historical events harbour more bitterness, are more critical and less inclined to reconcile themselves to them,” he says.

Awful and important

“I was surprised. I thought that people who had physically experienced a conflict might be the most bitter,” he says.

Part of the explanation may be that history is portrayed as worse than it was when parents tell their children about it.

“Parents tend to highlight the things that they believe were wrong and that should never be repeated. The awful events become important to share,” he says.

Andresen believes that a person who has lived through a conflict points out the difficult experiences because they want us to do everything we can to prevent the same thing from happening again.

‘Never again’ or bitterness

“People who’ve gone through such a traumatic experience think ‘never again,’ and they manage to let go of the bitterness. That’s why it’s important for these voices to be heard, so that the next generation doesn’t become too bitter,” he says.

Even people who originally came from a conflict area, but no longer live there, are bitter.

“They see things from the outside, get their information through the news and such, and they have a stronger tendency to only tell one side of the issue,” Andresen says.

He hopes that the research will lead to new tools that can help process difficult past events. He cites dark tourism as an example. People go to places where there has been conflict, like the Berlin Wall, Belfast or Auschwitz.

Digital hiking

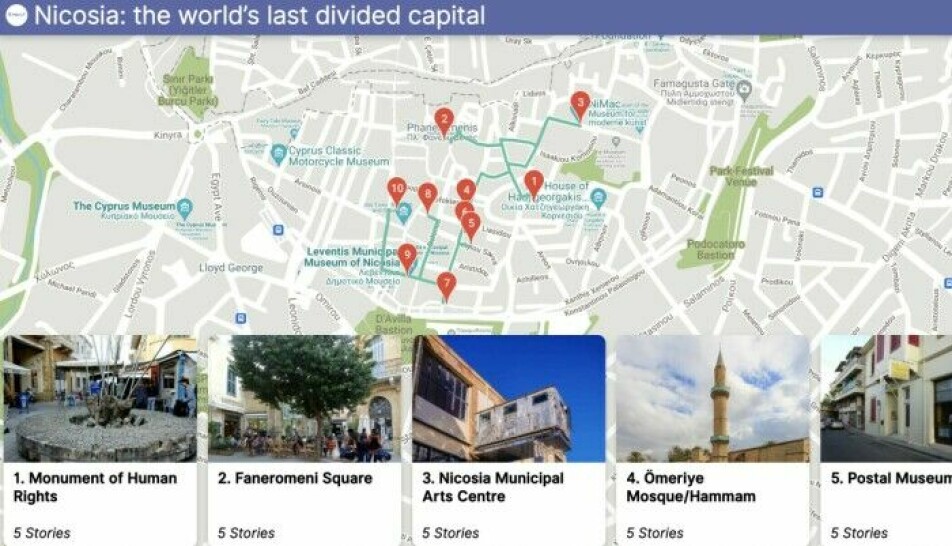

“What we’ve developed are concrete tools, like a digital hike. You can walk from memorial to memorial. You get quality-assured information through a location service, and then you’re quizzed at the end,” he says.

Currently, digital walks have been created that cover everything from women in the Spanish Civil War to the Jews in Thessaloniki. The University of Agder has now received money from the Research Council of Norway to use the same technology to tell about Norway's difficult historical periods.

“We’re planning to create a hike in Kristiansand, and maybe in Oslo, too. For example, we could go to a place where a Jewish family lived or where a deported Jewish family ran a shop. It doesn’t have to be about just World War II – we also want to do some newer things,” says Kenneth Andresen.

Recent past

Director Lena Fahre at the 22 July Centre – an exhibition that presents the terror attacks on that date in 2011 – has a sense for Norway’s more recent history.

“Traditionally there’s a lot of research on war and war events that are far back in time. We also need to try to understand our own recent past from both a local and international perspective,” she says.

Fahre looks forward to more research on how society has handled the terror of 22 July 2011 as the years go by.

“At this point, it’s difficult to say how the Repast project might be relevant to the situation since 22 July,” she says.

References:

Abit Hoxha and Kenneth Andresen: Violence, War, and Gender: Collective Memory and Politics of Remembrance in Kosovo. In Ana Milošević and Tamara Pavasović Trošt (editors): Europeanisation and Memory Politics in the Western Balkans, Palgrave Macmillan, Camden, 2021. ISBN: 978-3-030-54700-4. Summary.

Øyvind Bugge Solheim and Anders Ravik Jupskås: Consensus or Conflict? A Survey Analysis of How Norwegians Interpret the July 22, 2011 Attacks a Decade Later. Perspectives on Terrorism, June 2021, ISSN 2334-3745.

———

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no