This is where Neo-Nazi foreign fighters fought alongside communists

The foreign fighters came from extremist groups on the right and left. This didn’t stop them from working together.

During the 2010s, a number of people from the West travelled to conflict-ridden areas such as eastern Ukraine, Syria and Iraq to fight as foreign fighters.

These foreign fighters are often ideological radicals. They belong to extremes on the right or left. This doesn’t stop them from working together.

"We fought together, both Nazis and Communists, for the liberation of Russia," three anonymous convicted foreign fighters from Spain told the national newspaper El Pais.

Extreme right and left working hand-in-hand in Ukraine

“There are three colours you need to know about when talking about the ideological composition of the conflict in Ukraine: Brown, as in the far-right and fascism; red, as in the far left, Communists and the like; and white, represented by the Orthodox Russians who are fighting for a tsarist Russia,” said researcher Kacper Rekawek in a recent lecture at NUPI, the Norwegian Institute of International Affairs in Oslo.

“In one way or another, these different ‘colours’ managed to exist side by side, especially on the part of the separatists,” he said.

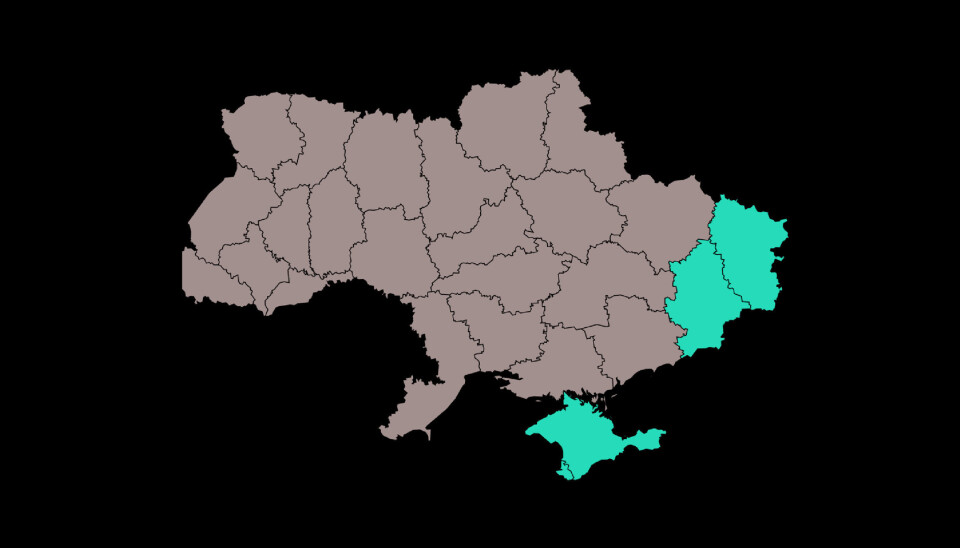

The separatists he refers to are the pro-Russian warriors in eastern Ukraine in the Donbass region, around the cities of Donetsk and Luhansk.

The conflict arose in the wake of political instability in Ukraine in 2013, and Russia's annexation of the Crimean Peninsula in 2014.

This "brown-red cocktail", as Rekawek calls it, can be explained by the fact that these extremists don’t feel that the people they’re fighting with don’t pose a danger to them.

Instead, what is crucial to them is what — or who — they perceive that they are fighting against.

“They tend to transfer their political and practical ideas to the conflict as an excuse to test themselves in war, because it is a masculine thing to do,” Rekawek says.

People who fought for the separatists sometimes said that they were ‘fighting against the Americans’, Rekawek said of the fighters he has talked to.

But Rekawek countered that there were no Americans in the region.

"People who fought on the Ukrainian side could also say they fought for a white Europe, but the separatists and Russia are predominantly white Europeans as well,” Rekawek said.

“The adrenaline often comes at the expense of politics, but politics is always present,” he said.

There were as many as 17,000 foreign fighters in Ukraine at one point. About 15,000 of these were Russians, while about 1,000 came from former Eastern bloc countries, such as Belarus. The rest came from land west of Ukraine.

One of these warriors was a Russian, Yan Petrovskiy. He had lived in Norway since 2004 and went to eastern Ukraine in 2014. There he fought on the side of the separatists.

In the time after he returned to Norway from the Ukraine, Petrovskiy was affiliated with "Odin's soldiers" in Tønsberg. He was arrested by the Norwegian authorities in Tønsberg in 2016 and sent back to Russia, after the Norwegian Directorate of Immigration (UDI) and the Norwegian Police Security Service (PST) determined he posed a threat to national security.

From Ukraine to Syria and Iraq

“The people who were involved in this conflict pop up in many interesting places —places where there is conflict, places for ‘the tough guys’", Rekawek said.

Researchers have seen former foreign fighters in Montenegro when there was a coup attempt there in 2016, and in Paris during the so-called Yellow Vest protest.

“Some people tried to be private military fighters in places like Syria. This is probably where Yan Petrovskiy ended up, where, according to an article on the NRK website, he was called “Norðmaður”, which is Old Norse for Norwegian,” Rekawek said.

Petrovskiy thus fought as a mercenary on behalf of the Syrian government.

“Some fighters also went to Iraq to join the Kurdish militias to fight IS,” he said.

“I have talked to several of them. I told them that these Kurds have pretty socialist views on things, and you're right-wing, so how does that work? They just answered that I was talking too much about politics — as long as they were fighting IS, it was fine,” he said.

Many foreign fighters saw the Kurdish militias in Iraq and Syria as a golden opportunity to fight IS and "Islamist terror".

“There are direct flights from Vienna to Erbil, and the Kurdish militias were mostly accommodating to foreign volunteers,” Nerina Weiss said to sciencenorway.no.

Erbil is the capital of Iraqi Kurdistan. Weiss is a social anthropologist at the research foundation Fafo and has studied the mobilization of foreign fighters who went to the Kurdish militias from 2014-2019.

Here, as in Ukraine, it turns out that the most important thing is that you be able to justify your actions ideologically, which means the ideology of the fighter you’re fighting next to is not so dangerous to you — as long as you all fight.

“They are basically fighting against something, not for something. What you fight for only comes when you are there,” Weiss said.

Through her studies of these foreign warriors, Weiss discovered that the conception that the fighters travelled on a so-called "purposeful" journey is probably not true.

She believes that the mobilization itself determines a lot.

“If, for example, you went to Syria with the aim of fighting against the Assad regime, it is absolutely crucial where you crossed the border into Syria and who controlled the area you entered,” she said.

Changed afterwards

“People tell stories in retrospect about purposeful journeys in a linear way, as in where I started and where I ended up, without describing all the choices along the way,” Weiss said.

“This story should make sense, but not all real stories do,” she said.

Sometimes it’s important that the story the person tells after the fact describes a warrior. Other times it’s important to tone down the person’s own involvement, such as when that person is questioned by authorities when he or she returns home.

“Many overplay their role and either say that ‘I didn’t fight much’ or ‘I was a professional soldier in a professional unit’,” Rekawek said, drawing a parallel to everyone who has excused their involvement with IS by saying that they were just cooks.

References:

Norwegian Institute of Foreign Policy NUPI, Foreign Fighters in the War in Ukraine, 22 March, 2021

Nerina Weiss, Good radicals? Trajectories of pro-Kurdish political and militant mobilization to the wars in Syria, Turkey and Iraq, Critical Studies on Terrorism, 27 April 2020, https://doi.org/10.1080/17539153.2020.1759955