In the forest in Løten, just east of the city of Hamar in Norway, these researchers will listen for earthquakes using common internet cables.

Can this technology help us store CO2 under the seabed?

Tremors in the pine forest

Fibre cables bring the internet to thousands of homes. But did you know that the cables can also be used to measure movement in the ground? The equipment is sensitive enough to pick up a cyclist passing by along a road.

Hidden among tall trees, and well into a pine forest in the little town of Løten, is one of the NORSAR research foundation's stations for monitoring earthquakes and explosions.

A small, white building sits at the centre of hyper-accurate seismometers. The instruments are placed in the forest in circles around the station.

The data coming from here and from NORSAR's other stations are analysed in Kjeller, northeast of Oslo. The most important task for these sensors is to monitor for nuclear tests.

When, for example, North Korea fires nuclear weapons, the explosion sends shock waves through the Earth, and an alarm goes off.

The station also picks up earthquakes in Norway and around the world, as well as explosions, or even just a slightly fat capercaillie that plumps down on the ground in the area.

NORSAR is now testing a new way of monitoring tremors in the ground.

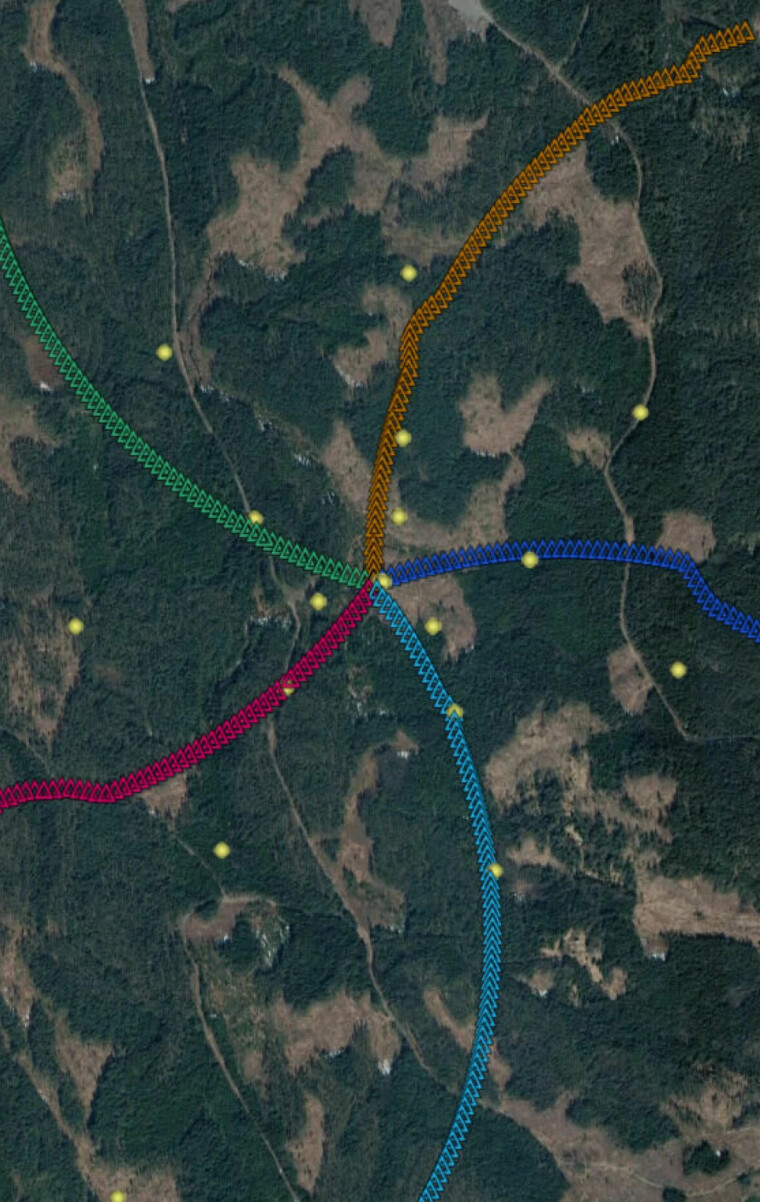

In addition to seismometers, the researchers have buried fibre cables. They extend like five long arms out from the station.

Opened this week

Work on burying the cables began in September last year. Now the test facility is ready, and was opened at the end of April.

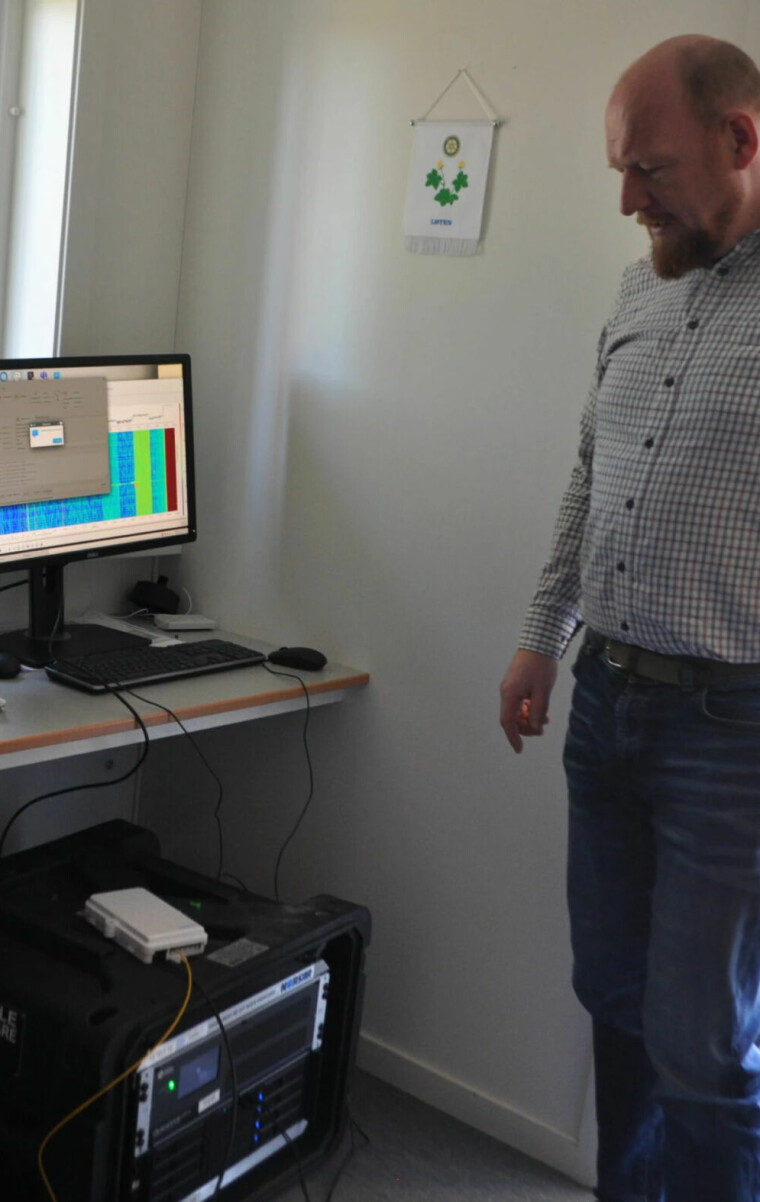

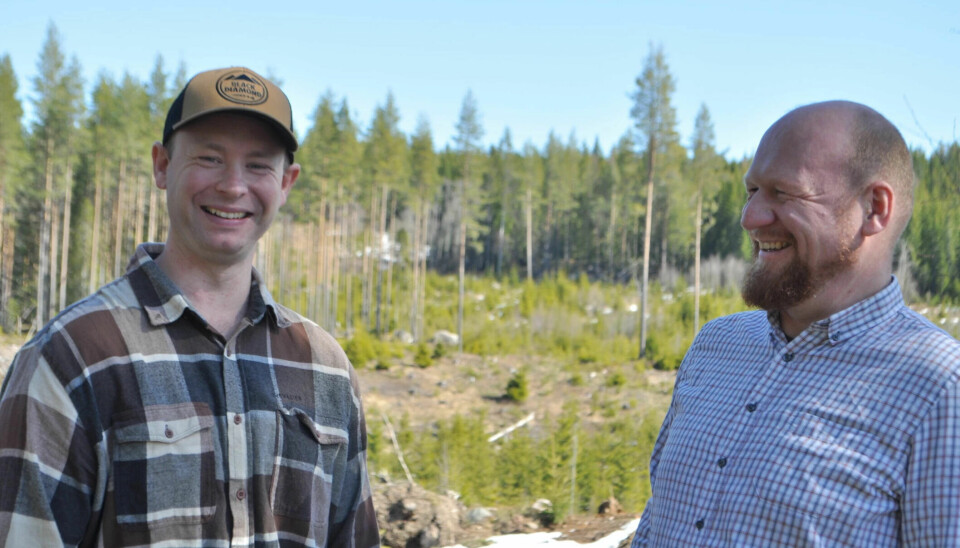

The leader of the project, Andreas Wuestefeld, and station manager Bjørn Christian Freitag meet sciencenorway.no at NORSAR's station at Stendammen in Løten.

Freitag has been in charge of the installation and points out where the cables are buried.

The trace of the buried fibre arm extends into the terrain.

Signs of forest clearing and truck tracks can be seen on the hill.

The fibre is buried half-a-metre deep, and stretches 1.5 kilometres to each side. The five arms meet in a covered drain outside the station building.

“This is actually exactly the same infrastructure that is used in internet cables,” says Andreas Wuestefeld, technology manager for fibre optics at NORSAR.

Laser pulses are sent into the cables, at a rate of thousands of light pulses per second.

Just inside the door of the building is the instrument that makes it possible to measure earthquakes with internet cables. On the floor is a square box called an interrogator.

The fibre cables measure earthquakes in a completely different way than seismometers.

A simple seismometer has a weight hanging from a spring. When the ground shakes, the frame around the weight will move, but not the weight itself. The seismometer measures the difference.

Fibre cables, on the other hand, use light to detect vibrations.

Extremely sensitive

When the light pulses travel through the cables, some of the light is disturbed by small irregularities that are spread randomly throughout the cable. A little light is then sent back to the interrogator.

“If there is a slight displacement of the cable, then the path will be a little longer for the light that is reflected back than otherwise,” says Volker Oye, head of research at NORSAR.

“We can see where along the cable there is a deformation, which means a stretching of the cable or a contraction,” he said.

The researchers can measure whether the cable is stretched just a tiny bit.

“If we have a kilometre-long cable, and it stretches by ten micrometres, then we can measure this,” Wuestefeld said.

A micrometre is one thousandth of a millimetre.

A signal appears

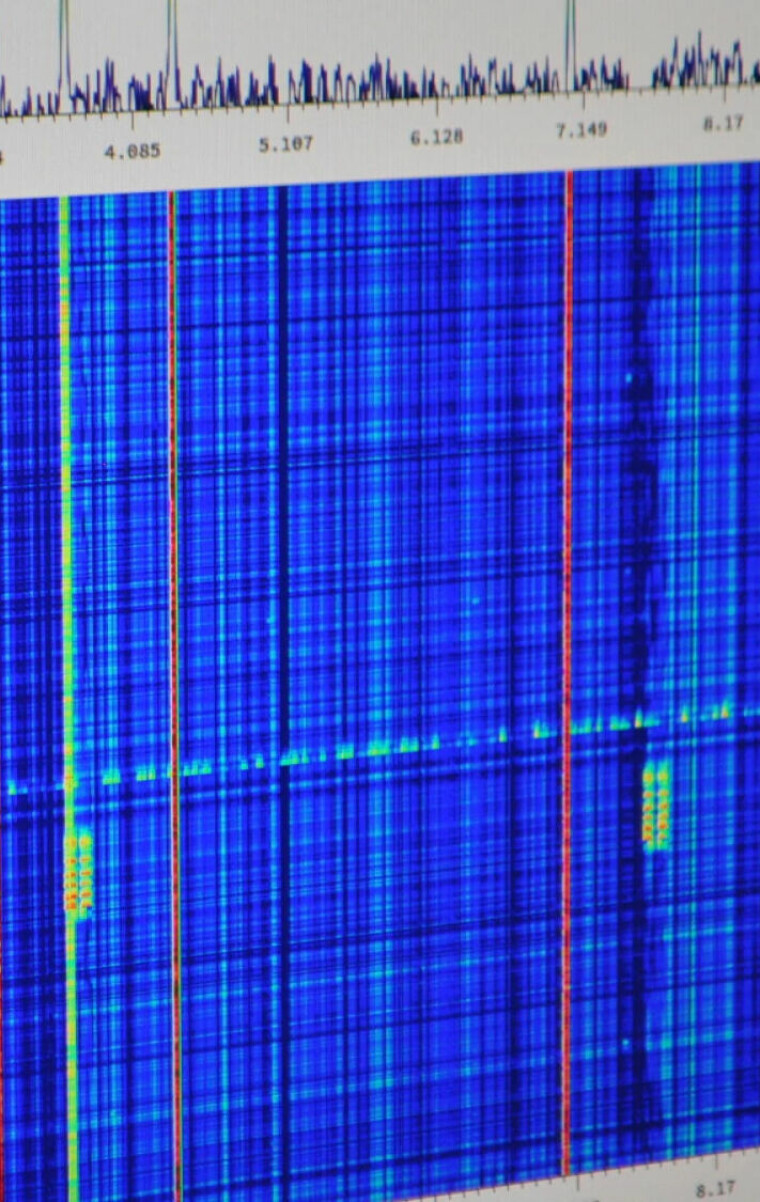

Ground movements are recorded in real time on a screen inside the station.

Right now it's quiet.

Bjørn Christian Freitag goes out and stomps five times on the manhole cover over the drain where the cables all meet. Suddenly, five spots appear on the screen.

Then a signal is picked up by only one of the arms.

“Something happened out in the forest,” Wuestefeld says.

Snow falling from trees or water in ditches after heavy rain can have an impact.

“Maybe it was a big capercaillie that sat down,” Freitag suggests.

A proper tremor will affect all arms.

Wuestefeld soon discovers a signal that appeared a short time ago.

“This isn't you, is it?” he asks Freitag.

It wasn't. Spots on the screen can be seen along the entire line at 12:00 noon

Was it an earthquake? Wuestefeld concludes that the movement probably originates from blasting in a quarry not too far away.

Can be connected to the fibre network

Wuestefeld and colleagues will analyse data that has thus far been received via the fibre structure.

The fibre cables have already detected earthquakes. They picked up on the earthquake in Turkey in February, says Freitag.

The fibre technology is slightly less sensitive to vibrations than the seismometers. But one advantage is that they can measure along the entire length of the cable.

Fibre cables are already buried in many places in Norway. It’s possible to connect instruments directly to these cable networks to measure ground movements.

“This is an idea for the future, to use Norway's internet fibre infrastructure to have more monitoring stations, particularly in areas where we don't have much monitoring now,” Wuestefeld says.

Detects landslides

At Stendammen in Løten, researchers will learn more about this way of measuring earthquakes and other tremors.

“Here you can compare good, proven seismometer technology with the new fibre technology,” says Freitag.

The researchers will test how well the fibre technology works, how sensitive it is and what kind of cable geometry is best, Wuestefeld says.

They can also test different interrogators and types of cables.

This is how the fibre cables are arranged underground at the station in Løten. This shape, with its slightly curved five arms, was rated as the best.

NORSAR is already working on a project in Norway’s northernmost counties of Troms and Finnmark, where fibre along roads is being tested to monitor avalanches.

The fibre cables allow the detection of landslides so officials can close the road if necessary. The technology is also sensitive enough to detect whether there are cars in the area, and even cyclists.

Fibre is already in use elsewhere to measure ground movements, Wuestefeld and Freitag said.

It is used in oil and gas fields and as security at airports to detect if someone goes where they shouldn't.

Aimed at CO2 storage

The test facility at Løten is specially designed to learn more about using fibre in connection with CO2 storage.

One possibility that is being seriously scrutinized as a place for CO2 storage is old oil and gas fields under the seabed.

“You want to be sure that the CO2 gas does not escape as a result of tremors or geologic faults in the seabed. You have to have good monitoring of the storage zone with seismic monitoring,” Wuestefeld said.

But placing seismometers or geophones on the seabed is expensive, Oye said.

With fibre cables on the seabed, it’s possible to monitor what happens to the gas and detect small leaks.

It is also possible to monitor the storage zone using fibre on land along the coast, Wuestefeld said.

Satisfied

Will the fibre facility at Løten be able to detect nuclear test explosions?

“We’ll probably be able to determine this as a result of the test phase we are in now. Fortunately, there are very few test explosions. But we have to see how good the resolution is in the fibre cables,” Oye said.

It takes a long time before a new technology is eventually approved for use in the international monitoring programme for nuclear test explosions, he says. There are strict requirements.

He is very satisfied with the new installation.

“It’s very exciting that we have managed to do this, and that it works so well. We are now in a phase of the project where we can allow guest researchers and others to test their equipment with us and make comparisons, both in Norway and internationally,” Oye said.

The overview picture of the five fibre cable arms was taken by NORSAR’s Andreas Wuestefeld.

Translated by Nancy Bazilchuk

———

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no