In some parts of the world, the ground has been frozen for thousands of years

Deep in the frozen ground, there may be both mammoths and saber-toothed tigers.

Some places in the world, including here in Norway, the ground is completely frozen.

Deep in what experts call permafrost, we can find prehistoric animals, often from the Ice Age.

But what exactly is permafrost, and how does it form?

Requires cold temperatures

It has to be really cold for permafrost to form.

"Permafrost is frozen ground that stays below 0 degrees Celsius for at least two years," explains researcher Line Rouyet from the research institute NORCE.

She explains that permafrost can form when a glacier sits on top of the ground for a very long time and then melts and retreats. The ground can remain frozen long after the glacier is gone.

And in some places, the ground never thaws, even after thousands of years.

"In some places, we find permafrost that's several hundred thousand years old," says Rouyet.

On Dovrefjell, a mountain range in Central Norway, there is permafrost that is 100,000 years old, according to Norwegian Broadcasting Corporation NRK (link in Norwegian).

Deep beneath the ground

Above the permafrost, there is always a layer of soil or rock that thaws in the summer.

The thickness of this layer varies. Some layers are only a few millimetres or centimetres thick, while others can be several metres deep.

This means that the permafrost can be located quite far beneath the surface.

"At Juvvasshøe in the Jotunheimen mountains, we have a borehole that is 120-130 metres deep. Temperature measurements have been taken there since 1999," says researcher Karianne Staalesen Lilleøren.

Researchers use these boreholes to monitor temperatures over time. This helps determine if the permafrost is warming.

Covers large parts of the world

Although researchers do not know exactly how much permafrost there is in the world, they do know that it covers a vast area.

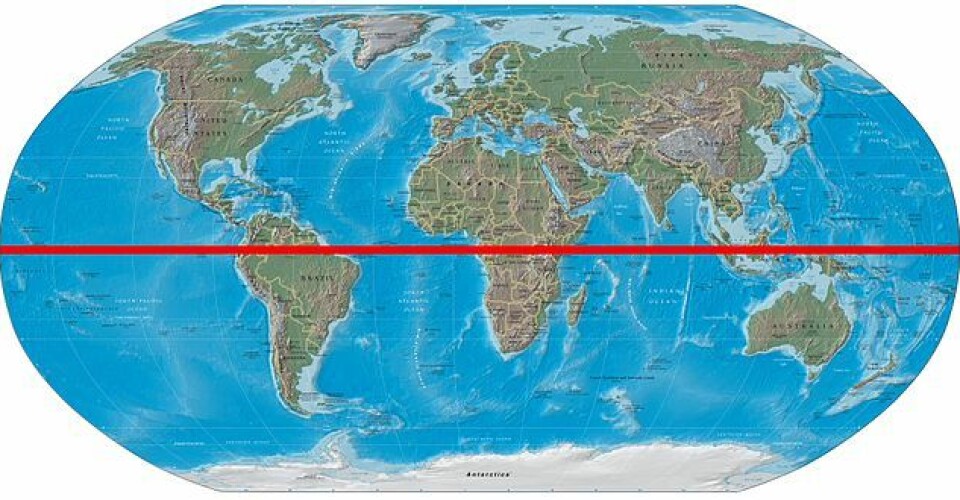

"About 15 per cent of the northern part of the world is covered by permafrost," says Rouyet.

The equator divides the Earth into two halves: the northern and southern hemispheres.

Norway is part of the northern hemisphere.

"Permafrost is mainly found in polar regions and high-altitude areas, with most of it located in the Arctic," she says.

Prehistoric animals

In 2024, researchers found a saber-toothed cub.

It was found in the permafrost.

The cub had been buried in the frozen ground for over 30,000 years but still had its fur, whiskers, and claws intact.

According to this research article, it is one of 16 Ice Age animals that have been found in permafrost.

Mammoths are the most commonly found prehistoric species.

———

Translated by Alette Bjordal Gjellesvik

Read the Norwegian version of this article on ung.forskning.no

Subscribe to our newsletter

The latest news from Science Norway, sent twice a week and completely free.