Previously unknown particle increases ocean acidity

Until recently, nobody knew tiny calcium carbonate particles are prolifically found in the open sea. Their origin is a mystery but climate change models will need to take them into account.

Denne artikkelen er over ti år gammel og kan inneholde utdatert informasjon.

The amount of calcium carbonate in the sea is crucial. A higher production of it increases the acidity of the water and levels of CO2.

“The atmosphere is affected when oceans contain higher concentrations of this greenhouse gas because less additional CO2 can then be absorbed by the sea,” explains Gunnar Bratbak, professor of microbiology at the University of Bergen (UiB) in Norway.

He thinks the newly discovered particles can fill an important vacuum in today’s climate models, because without these particles oceans would be less acidic and could sequester more atmospheric CO2.

Like other scientists, Bratbak fears that as the oceans grow more acidic the world’s coral reefs will be increasingly imperilled.

“A simultaneous consequence of mounting ocean acidification is its impact on shell production, for instance oysters,” says Bratbak.

Specks take shape

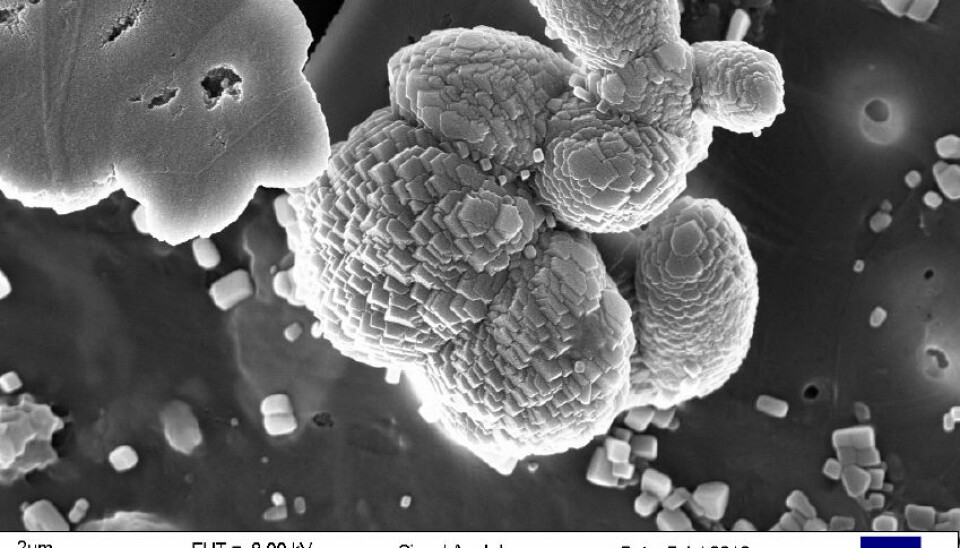

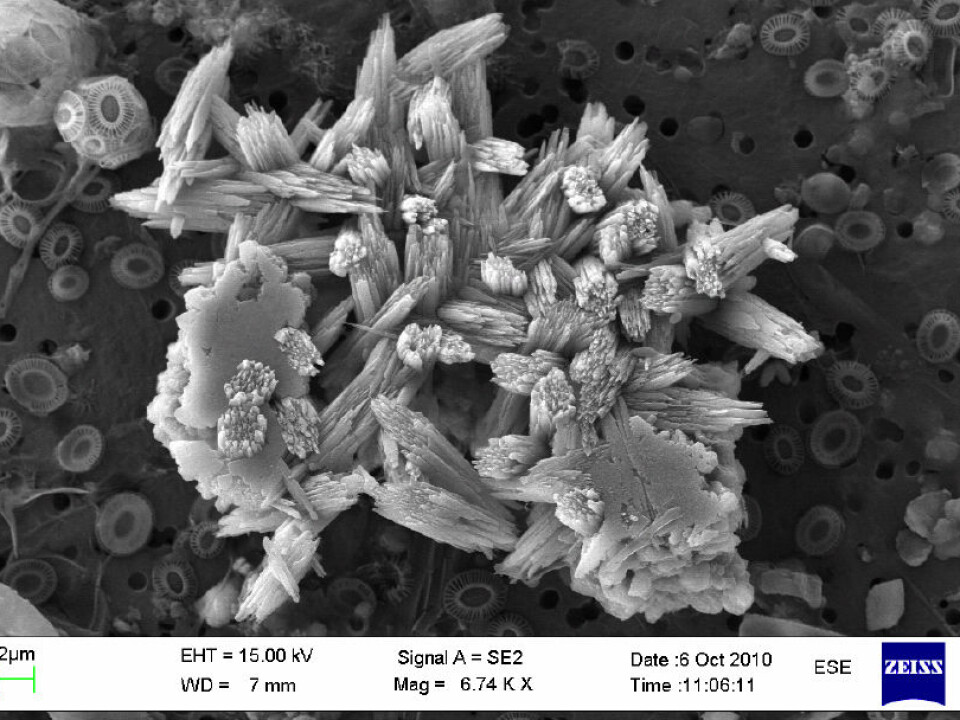

An electron microscope enabled the researchers to reveal these particles in the Norwegian Sea and elsewhere.

Co-authors Mikal Heldal and Egil S. Erichsen used it to reveal contexts, variations and new discoveries where you and I might only see large specks in an ordinary microscope.

“The discovery of these particles in the open sea by no means represents a quick fix to the climate problem,” says Bratbak.

Nevertheless, knowledge of the existence of these particles can fill in some holes in today’s climate models.

“Such models are significant for predictions of developments of the Earth’s climate. By including the new particles we can more accurately determine the effects that higher amounts of CO2 will have on the oceans − and in turn on global climate,” says Bratbak.

“One of the major uncertainty factors in the models used to describe the relationship between the climate, developments in the sea and the atmosphere involves the natural production of calcium carbonate in the ocean,” he explains.

In Norwegian fjords and the Mediterranean

The newly discovered particles contribute to the creation of more calcium carbonate over a longer timespan than do other processes which produce CaCO3, according to the study which was recently published in the journal PLOS ONE.

The shapes, quantities and sizes of these particles vary, but most are from 0.001 to 0.1 millimetres in size and they number from 10,000 to 100,000 per litre of seawater.

“We’ve found the particles in the Norwegian Sea, in the fjord outside Bergen, the coast of Svalbard, in the Mediterranean and in North Sea sediments. We find them on the surface and down at depths of 1,000 metres.”

“Until now we thought the most important producers of calcium carbonate in the oceans were coralline algae, protozoa and sea butterflies,” adds Bratbak.

Protozoa are unicellular organisms and thousands of species are found around the planet.

Seeking knowledge about production

X-ray analyses were made of the newly discovered particles to reveal their content, which is mainly CaCO3 – in other words calcium, carbon and oxygen.

The next step for Bratbak and his colleagues will be to try and find out how the production of these particles occurs.

“Right now we don’t know where or how this process takes place.”

“It probably occurs in the upper metres of the sea, perhaps at the very surface, and we think the production is largely attributable to bacteria,” says Bratbak.

Which bacteria?

So one challenge will be to find out which bacteria are in action and determine the environmental conditions that are involved in influencing the process.

“We figure this is a wholly natural process. There isn’t anything we humans are doing which contributes to the formation of these particles,” says Bratbak.

If the scientists can find an answer to why, how and under which conditions the particles are formed, they might be able to improve our understanding of the consequences of increased CO2 and acidification of the oceans.

“We can certainly say that if these calcium carbonate particles were not being produced, the ocean would be less acidic and it could absorb more CO2 from the atmosphere,” says the professor.

In addition to researching the processes involved in the formation of these particles, the scientists will also investigate factors impacting their production rate.

----------------------------

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no

Translated by: Glenn Ostling