Massive snowfall and unusually freezing temperatures in Norway – why is this happening now?

Norway is experiencing extreme weather. A temperature of minus 43.5 degrees Celsius was recorded in Kautokeino. In other places in Norway, schools are closed due to large amounts of snow.

In Kautokeino, a temperature of minus 43.5 degrees Celsius was recorded on Thursday.

In Oslo, the forecast for Friday and Saturday was down to 30 degrees below zero, but this was later adjusted to just under 20 degrees below zero.

Residents of Kvikkjokk in Northern Sweden experienced minus 43.6 degrees on Wednesday. This is the coldest January day recorded in Sweden in 25 years.

A weather phenomenon that occurs about every other year increases the likelihood of even colder temperatures in the coming days.

The extreme cold spell could last for up to 40 days.

Tonnes of snow

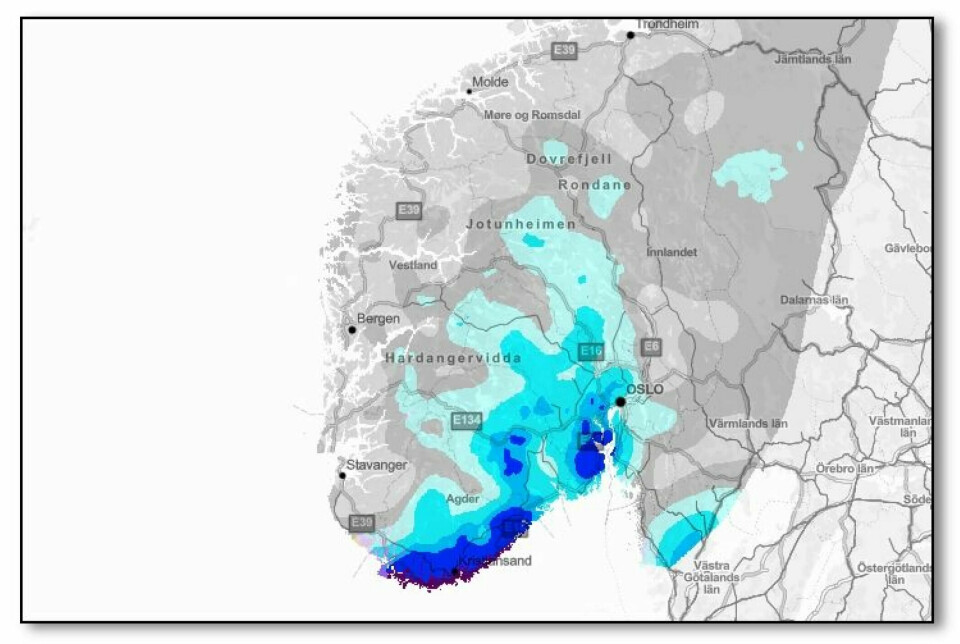

The snow has also caused chaos in Southern Norway. Cars and buses are stuck. Schools and after-school programmes remain closed, and people have lost power.

The climate on Earth is becoming warmer and wetter.

But when it's as cold as it is now, the increased precipitation falls as tonnes of snow.

Moist air from the west

But why is it snowing so much specifically in Southern Norway? Here's the explanation:

Moist air from the Atlantic Ocean is moving across Norway.

When this moist air from the west meets colder air masses over land, a lot of snow can fall in Southern Norway during the winter.

Extreme cold in Scandinavia

“Right now, there’s an ice-cold high-pressure area over the Gulf of Bothnia between Finland and Sweden. The cold air mass reaches as far south as Southern Norway,” Lillian Kalve, the on-duty meteorologist at the Norwegian Meteorological Institute, says.

Typically, this moist Atlantic air impacts the West Coast of Norway, which is further to the north.

“However, the cold high-pressure system is pushing the low-pressure area carrying moist air southwards towards Denmark, leading to Southern Norway receiving the precipitation instead,” she says.

Add to this the fact that the low-pressure system over Denmark is swirling counterclockwise. You can see how the wind direction carries the precipitation inland over Southern Norway.

Furthermore, the topography of Southern Norway, characterised by elevations and mountains, forces these moist air masses upwards into the air and cool down.

This results in the precipitation falling as snow in the region.

Wet winters in Southern Norway

Most viewed

In Southern Norway, it is noticeably becoming both warmer – and wetter.

The last 30 years have seen significantly more years with high precipitation in Southern Norway compared to most of the 20th century. The temperature has also risen by about one degree.

And the winters in Southern Norway have become more prone to heavy precipitation.

Comparing data from the Norwegian Meteorological Institute since the 1990s to earlier in the 20th century, there's a clear increase in the number of winters with significant rainfall.

Why is it so cold now?

Strong

vortex around the North Pole

“Above us, at an altitude of 20-30 kilometres in the stratosphere, a strong vortex typically circulates around the North Pole during winter,” Tore Furevik says. He is director of the Nansen Center in Bergen.

This polar vortex forms due to the dark and extremely cold conditions in the far north during winter.

Occasionally, something extraordinary happens: The vortex around the North Pole collapses.

This is likely what is happening now.

The cause is atmospheric disturbances.

Climate researchers suggest that large mountain ranges might be causing these disturbances, as they can send waves rippling up through the atmosphere, reaching the vortex in the stratosphere over the Arctic.

This winter, the stratosphere over the Arctic has been abnormally cold.

“However, in a matter of days, we could see a warming of up to 50 degrees in the stratosphere over parts of the Arctic, possibly even more,” Furevik says.

The whole of January might be cold

Such major changes and sudden warming in the stratosphere will in turn affect the lower layers of the atmosphere, potentially leading to colder conditions at ground level.

Based on previous similar events, Furevik and other climate researchers know that this cold spell can last a long time.

Sometimes up to 40 days.

“It’s not unlikely that the whole of January will be colder than what we are used to,” Furevik tells sciencenorway.no.

Not a yearly winter phenomenon

The phenomenon is called Sudden Stratospheric Warming (SSW).

On average, this phenomenon occurs roughly every other winter, sometimes even more frequently.

The current conditions in Norway are therefore not typical of an ordinary winter.

But some years, Norway experiences sudden atmospheric warming twice in the course of the same winter.

What about global warming?

In 2023, our planet has experienced record warmth.

So, how can there be such extreme cold in various regions during winter?

“Despite global warming, periods of cold temperatures are still possible,” Furevik says.

Climate researchers are yet to gather sufficient data to conclusively determine if global warming will increase the frequency of these sudden stratospheric warming events. And whether it will lead to colder conditions down here at ground level.

They are also unsure if the intensity of cold spells will increase alongside global warming.

Warm Arctic = cold Europe

Furevik and colleagues at the University of Bergen’s Geophysical Institute and the Nansen Center have conducted extensive research into how cold winters across much of Europe and Asia – Eurasia – are linked to warming in the Arctic, at the top of the globe.

- The Arctic has warmed at a rate more than twice the global average since the mid-20th century. Hardly any other place on Earth has experienced higher warming than Svalbard.

- Europe and Northern Asia have been experiencing an increase in the frequency of cold winters.

Several studies by climate researchers in recent years have examined this particular correlation.

There has been considerable debate among scientists in this area.

Furevik and colleagues have conducted a study that attempts to reconcile these differing viewpoints, concluding that both sides may be correct.

“We have demonstrated through observations and models that the likelihood of cold Eurasian winters is higher when there is unusually warm weather in the Arctic. This Arctic warming is a result of increased heat and moisture transfer from the North Atlantic,” Furevik says.

———

Translated by Alette Bjordal Gjellesvik

Read the Norwegian versions of these two articles here and here on forskning.no

References:

He et al. Eurasian Cooling Linked to the Vertical Distribution of Arctic Warming, Geophysical Research Letters, 2020. DOI: 10.1029/2020GL087212

Outten et al. Reconciling conflicting evidence for the cause of the observed early 21st century Eurasian cooling, European Geosciences Union, vol. 4, 2023. DOI: 10.5194/wcd-4-95-2023