The passive housing revolution

Seventy percent cuts in carbon emissions and 75 percent cuts in energy consumption by 2050? Passive house technology could make it happen.

Denne artikkelen er over ti år gammel og kan inneholde utdatert informasjon.

Despite a projected increase in Norway's population to seven million by 2050, it will be possible to drastically reduce the country's energy consumption compared to current levels, claims Stefan Pauliuk at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU).

Analysing the industry, transport and housing sectors, his doctoral thesis uses complex calculations to compute the state of energy consumption and emissions by 2050 under different scenarios.

A third of Norway's electricity consumption

Using 35 out of 112 terawatt hours, the housing sector accounts for almost a third of Norway's total electricity consumption and is one one of the largest sources of carbon emissions.

“Housing is the easiest sector to tackle if we are to reach climate targets,” he points out.

“The so-called 'green' electricity we produce should ideally be used on other things than heating homes – such as electric cars, or the metal or oil industries. Overall, it could replace much of current fossil fuel consumption. If we are to meet our own and the UN's environmental targets and show that we take this seriously, it's the obvious place to start.”

Norway has pledged to become 'carbon neutral' by 2030, and UN targets demand a 80-percent reduction in global emissions by 2050.

Calculating gains from passive houses

Working with Karin Sjöstrand and supervisor Daniel Müller, Pauliuk has calculated how much energy could be saved by building or adapting the entire Norwegian building stock to so-called 'passive standard'.

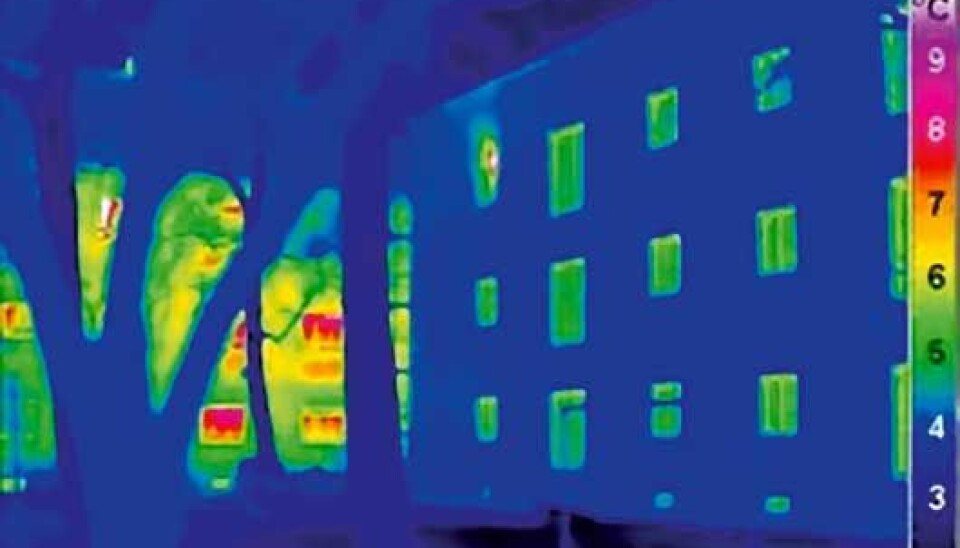

A 'passive house' gets nearly all its energy from solar energy, electrical appliances and the residents themselves, through 'passive' measures such as heat insulation, high-density building materials, solar panels, well-fitted windows and a heat exchange system extracting heat from the circulated air. Of the entire housing stock, only around 100 houses are currently built to meet this standard.

The model includes a range of parameters such as population growth, energy demand, different ways of living, and CO2 emissions and other environmental impact from construction, demolishing and retrofitting.

“No-one has ever developed models with all of these variables before,” says Pauliuk.

A variety of scenarios

The model calculates the effect of these variables under different scenarios ranging from continuing as today, through a combination of passive new build and retrofitting of older houses, to a complete rebuild of the entire housing stock. A reduced living area per person or investing in more effective water heating and electrical appliances are also included in the variables.

The calculations show that the last two measures, along with passive new build and retrofitting of older stock, would give the greatest savings. In this scenario, the current energy consumption of 34 terawatt hours would be reduced to 10 terawatt hours by 2050 – even with a larger population and the environmental impact from construction and adaptation taken into consideration.

Pauiliuk argues that a complete upgrading of the building stock to a passive standard is feasible.

“It would obviously entail some difficulties and require a 40-year-long commitment as well as major investments," he says. "But considering the future costs of carbon emissions and the increased demands on the energy market, these measures are likely to prove cost effective.”

------------------------------

Read the full story in Norwegian at forskning.no