This is how climate change is impacting our nature right now

“This is a very strong signal to take better care of nature,” says one researcher.

On the 28th of February, the UN Climate Panel launched part two of the sixth assessment report on climate change. This report addresses the impacts of climate change, vulnerability and how we can adapt.

One of the report's main messages is that human- and ecosystem-vulnerability are intertwined. If we don't change course in a more sustainable direction, both the planet's people and nature will become even more vulnerable.

The report provides an updated picture of how nature is changing and what we can expect going forward.

According to the report, 3.3 to 3.6 billion people are vulnerable in the face of climate change. Many species are also endangered.

Shocked by scope of changes

“I’m struck by the extent of the changes we see in nature, but of course also how many people actually are feeling this in their bodies. The two are very closely linked,” says Mette Skern-Mauritzen.

She studies marine ecosystems at the Norwegian Institute of Marine Research and is one of the researchers who has been involved in writing the report.

“As bigger changes happen in our ecosystems, they have consequences for us as well,” says Skern-Mauritzen.

She recently presented results on the impacts of climate change in the oceans and on land at the Norwegian Environment Agency's recent press conference (link in Norwegian).

Species on the move

Researchers are already seeing impacts everywhere in nature, according to Skern-Mauritzen.

“That’s probably the main message. There aren’t any places that are unchanged,” she says.

“Species are on the move. This means that within a geographical area, the biological diversity is changing.”

The seasons are also shifting. Spring is starting earlier.

Of the 4000 species studied, half are already modifying their ranges. They have moved north, south, up slopes or spread out from their traditional distributions. This means that new compositions of species are gradually emerging in the ecosystems.

Marine species are moving an average of 60 kilometres per decade. Terrestrial movement is somewhat slower.

Two-thirds of the species have also changed when they start their spring activities, including everything from when flowers bloom to when animals breed.

Mixed biodiversity trends

Skern-Mauritzen explains how these shifts are reflected in Norwegian marine habitats. Fish and other marine animals are moving.

“We’re seeing these shifts here too. We’re finding increasing biological diversity and we’re catching more species than we did before.”

In the North Sea, climate change has had a negative effect on fish stocks.

“There we see that the cod fish stocks are declining. It's getting too warm for them,” says Skern-Mauritzen.

Other species may benefit from warming temperatures.

“We believe that the population we’re harvesting from in the Norwegian Sea and the Barents Sea is relatively robust, given the climate change that is taking place.

Everything should fall into place in the spring

The climate controls a lot of marine activity,” says Skern-Mauritzen.

“What happens in the spring is incredibly important, both on land and in water. After a long dark winter, spring is when everything happens.”

Off the Norwegian coast, algae and zooplankton undergo a spring bloom. The fish spawns are timed for this, so that the fry will have plenty to eat. And the seabirds' egg-laying period is in turn timed to intercept the abundance of fish fry in the ocean,” says Skern-Mauritzen.

“If some species start earlier in the spring than others, it can lead to a break in the food chain. We really know very little about the impact of this type of indirect effect that happens through the food web.

Wood-eating bugs

Plants and animals aren’t the only ones on the march. Pests on land are also moving.

Harmful insects in forests have become more widespread and caused more serious damage in North America and Northern Europe due to warmer winters, according to the summary in Chapter 2 of the report.

Large forest areas in Germany have been destroyed, partly due to drought and insect infestation, according to The Guardian.

The researchers also write that several diseases in nature have changed their distribution area and are emerging in new regions, such as illnesses caused by ticks, parasitic worms and chytrid fungi (which are dangerous for amphibians).

Mass mortality events

The new report gives more attention to extreme events in nature.

“This is a topic that hasn’t received such a strong focus before,” says Skern-Mauritzen.

Climate change is causing more frequent and more severe extreme events to occur, such as droughts, heat waves, fires and flooding.

At the recent launch of the report under the auspices of the Norwegian Environment Agency, Skern-Mauritzen referred to the large heat wave in the Pacific Ocean that peaked in 2014 and 2015 and was nicknamed “The Blob.” In parts of the affected area, the temperature was six degrees higher than normal.

“This heat wave caused mass mortality among seabirds and marine mammals, as well as a fisheries collapse,” she said.

“The degree of warming and the ecological consequences we observed then are in a way what we expected around the year 2100, given the worst case scenarios for global warming. But with these extreme events, we’re already seeing that impact.”

Ocean heat waves have already bleached corals and destroyed kelp forests.

"Both corals and kelp forests are ecosystems that have major consequences for biological diversity," said Skern-Mauritzen.

Local extinctions

Heat waves also impact terrestrial life.

Heat waves in Australia, North America and South Africa have led to mass deaths and reduced health and fewer offspring of some species of bats and birds, and have affected their daily activity and geographical distribution, according to the new report.

For example, Australia has seen several cases of mass deaths among fruit bats. Thousands of bats dropped dead from trees in 2017, the Sydney Morning Herald reported.

Elsewhere, new maximum temperatures have caused species to disappear locally.

The UN Panel on Climate Change writes that local extinction caused by climate change has been widespread, and that it has been detected in 47 percent of the 976 species studied, according to this study in PLOS Biology.

When a species disappears or moves from an area, it can affect other parts of the ecosystem.

Fire and shifts in vegetation

Burned areas could potentially increase by 35 percent at two degrees of warming and 40 percent at four degrees of warming, the researchers write in the Chapter 2 summary.

Shifts in vegetation could occur in 15 percent of land areas with a warming of two degrees and 35 percent at four degrees.

These shifts might, for example, mean that forest areas turn into grasslands or vice versa.

In scenarios with high warming, models suggest that large parts of the Amazon rainforest will be drier and that the vegetation will decrease there. Coniferous forests will also creep northward and into what is presently a treeless tundra in the Arctic.

Species at high risk of extinction

According to the report, climate change will increase the risk of some species disappearing.

At 1.5 degrees of warming, 3 to 14 percent of the examined species are likely to be critically endangered and thus have a high chance of extinction. Critically endangered is defined here as the species losing at least 80 percent of climatically suitable habitats.

At 2 degrees, the researchers estimate that between 3 and 18 percent of the species will become extinct. The median is 12 percent. At four degrees the numbers are between 3 and 39 percent with a median of 13 percent.

Many species are already endangered today. The main cause is loss of habitat. How humans use land areas and climate change will determine how the species fare.

Biodiversity threatened

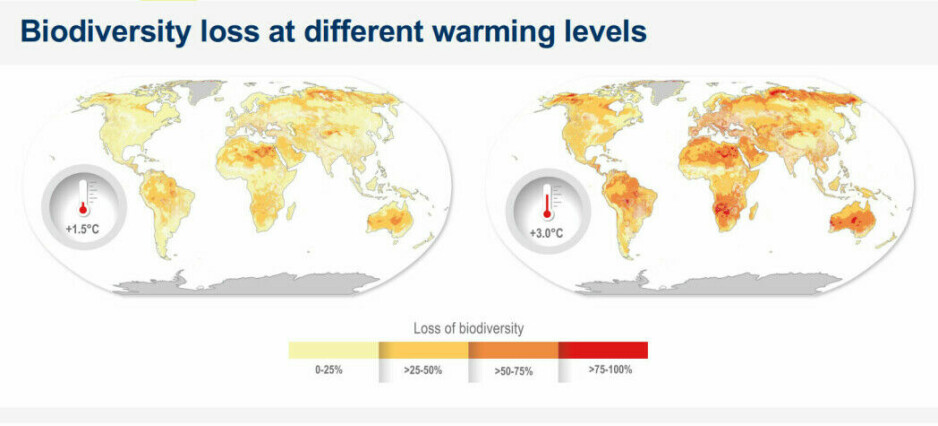

The calculated changes for biodiversity are dramatic.

Researchers have calculated the risk to biodiversity by looking at how many species lose at least half of their climatically suitable habitats. The species is then defined here as endangered.

"The percentage of species estimated to be endangered (or worse) was 49 percent for insects, 44 percent for plants and 26 percent for vertebrates if global warming rises by nearly three degrees," the report said.

The largest losses are expected in northern South America (including the Amazon), South Africa, most of Australia and in the far northern reaches.

The figure below shows what percentage of species in different areas are expected to become threatened or extinct. In large areas, between 50 and 70 percent of the species that live there now will struggle if temperatures rise by three degrees.

Emissions from nature could increase

In addition to fires and pests, forests can be damaged directly by drought. More than 100 cases of tree mortality due to drought have been detected in Africa, Asia, Australia, Europe and the Americas, according to the report.

Terrestrial vegetation still fixes more carbon than it emits. Continued climate change may cause more carbon to be released into the atmosphere due to fires, tree mortality, harmful insects, drying out of bogs and melting permafrost.

Large-scale protection of nature recommended

During the report's launch, Skern-Mauritzen said researchers are observing that ecosystems in a bad state are more vulnerable to climate change than areas in healthy ecological condition.

“We see that fragmented forest areas or drained wetlands combined with climate change are more susceptible to fires and droughts.”

Protecting and restoring nature will make ecosystems stronger in the face of climate change.

According to the climate panel, analyses indicate that we need to take care of 30 to 50 percent of terrestrial, freshwater and marine habitat.

“This is new information,” Skern-Mauritzen says.

This does not necessarily mean that 30 to 50 percent of nature should be protected from all human intervention, as she interprets it.

“These concepts can be a bit difficult. The report actually does not say protection, but conservation. So at the moment I think what all this means exactly is a bit unclear.”

Strong signal

“In any case, this is a very strong signal to take better care of our nature, and that we need to give nature the space and flexibility to adapt to climate change,” says Skern-Mauritzen.

“It’s been clear before now as well, but this was a very concrete indicator from the IPCC that hasn’t been given before.”

The Climate Panel believes it is important to ensure ecosystem robustness going forward. This could be important in fisheries management, for example,” says Skern-Mauritzen.

“In fisheries, we have a goal of optimal long-term yield – that we’ll harvest as much of the large stocks as possible. It’s assummed that the stocks are sustainable.”

“But now, with needing to pay more attention to nature and giving ecosystems more leeway, we have to begin to see how we can reap the benefits of nature that not only yields maximum benefits for us within a sustainable framework, but also builds nature’s inherent robustness,” Skern-Mauritzen says.

“We might end up with a slightly different answer than if we only focus on long-term yields,” she says.

———

Translated by Ingrid P. Nuse.

Read the Norwegian version of this article on forskning.no

References:

The Sixth Assessment Report from the IPCC, Part 2: Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability: Summary for Policymakers, 28 February 2022.

The Sixth Assessment Report from the IPCC, Part 2: Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability: Chapter 2 on Terrestrial and freshwater ecosystems and their services, 28 February 2022.