No gifts, no society: “It's strange how little people know about why we give each other gifts.”

“The exchange of gifts is the glue that holds society together,” one researcher says.

Giving Christmas presents is a long tradition, but how aware are we of what’s going on when we give each other presents?

Why do we give each other gifts?

“This is what we call a community,” says Runar Døving, a social anthropologist and professor at Kristiania University College.

He has no doubts about the importance of gifts for society.

“Without gifts, no society. Gifts are relationships. They are absolutely necessary. The exchange of gifts is the glue that holds society together,” Døving said.

“The whole family unit is based on gifts. That’s the natural human form of economics,” he said.

The difficult deferred exchange

One of the things that separates the gift economy from the market economy is that a gift exchange is a deferred exchange.

In the market economy, the exchanges are direct. The supermarket gives you milk and you give the supermarket money. An equal exchange. Finished, done, no contact.

“But if I give you 50 dollars, now you have a problem,” Døving said.

That’s because when you accept a gift, you incur a duty to give the other person something in return.

“But if you shop in the store, you put the goods on the belt, pay and put them in a bag, and then the relationship is over. You don't have to relate to the person behind the till,” Døving said.

While an exchange of goods is direct, anonymous and legal, a gift exchange on the other hand is relational, deferred and reciprocity-oriented, according to the professor.

Logically speaking, we have no obligation to give someone a gift, but it can damage the relationship between you and the person who gave you the gift if you don't give something back.

“When you accept, you incur an indirect debt. You feel that you have to give something back,” Døving said.

That’s how you build connections.

“It’s the debt that creates the relationship,” Døving said.

And if you want nothing to do with the relationship, you either don't give back or you refuse to accept the gift, he said.

“Then the relationship disappears,” Døving said.

I (still) like you

According to what is called gift theory, the function of the gift is to connect or establish social ties.

In other words, the gift serves either as a reminder that the friendship, or the relationship between you and your relatives or partner is still close and good. The gift can also serve as a proposal to a person with whom you would like to have a closer relationship.

“Gifts always, everywhere, imply a confirmation or establishment of social cohesion,” says Svenn Torgersen, a professor emeritus of psychology at the University of Oslo.

We use Christmas presents to show that we belong to a group, according to Torgersen. In this context, this would be a group that gives gifts to each other, such as a family or circles of friends, Torgersen said.

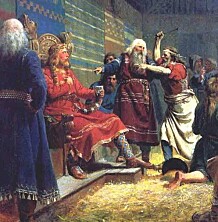

“We use gifts to confirm or establish some kind of contact. It’s always been that way. People used to bring gifts with them when they met the chief from the neighbouring tribe, as a way to confirm or establish ties,” he said.

And in many ways we haven't changed that much since.

“If a foreign leader comes to Norway for a royal visit, they always bring gifts. The castle is full of gifts that they don't know what to do with,” he says.

The soul of the gift

If you receive a gift that you absolutely do not want, then the best thing you can do is give the gift to someone else, sell it, or throw the gift away. But very few people are comfortable doing that.

“When you give the gift, you come along as part of the gift. This makes it difficult to give the gift away or throw it away. Norwegian cupboards are full of objects that you cannot give away because you have received them as a gift,” Døving said.

The French sociologist and anthropologist Marcel Mauss is often referred to as the father of gift research. Døving explains how he used the New Zealand Maori term ‘hau’ to explain what he calls the soul of the gift 100 years ago.

An object that is given from one person to another as a gift carries with it ‘hau’, meaning the soul of the gift. If the gift is passed on from the second person to a third person, the ‘hau’ follows, according to Mauss's theory.

Awareness of the gift's function

A study on Christmas gift trends from 2012 by the Norwegian National Institute for Consumer Research (link in Norwegian) showed that only between 20 and 30 per cent of the population believe that a gift strengthens or weakens social ties. But if we are to believe the theory of gift giving, this is the entire function of the gift.

Is it possible that we are simply not aware of why we buy each other gifts?

“It’s strange how little people know about why we give each other gifts. Learning about gift exchange is one of the first real aha experiences anthropologists have, because everyone recognizes themselves in the practice. The fact that we don’t teach this during the 12 years that children are in school in Norway is a bit odd,” Døving said.

Translated by Nancy Bazilchuk

———

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no