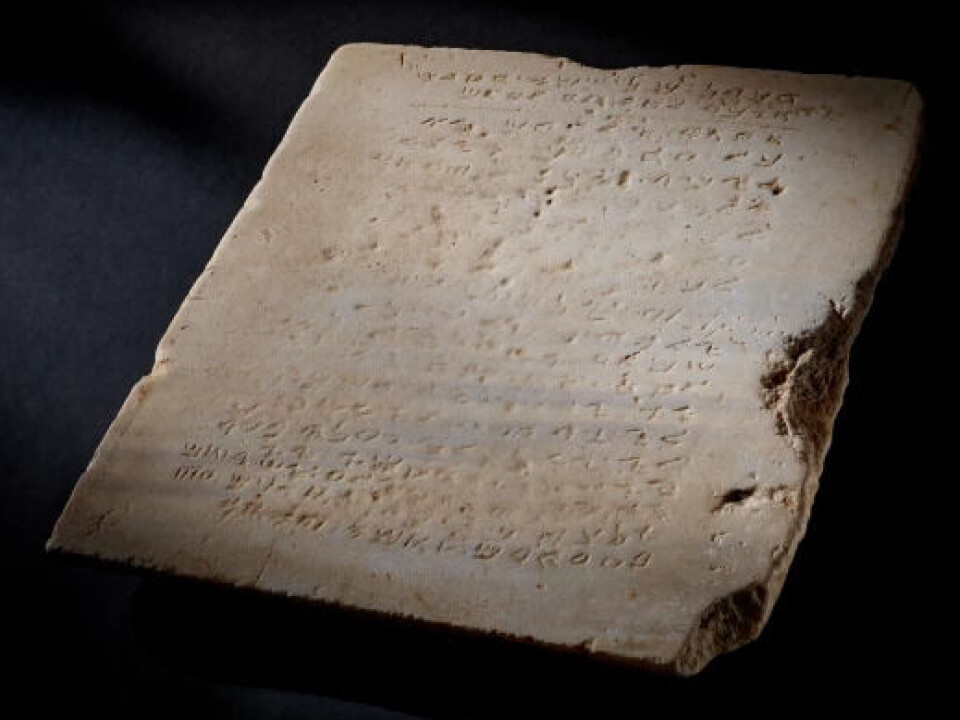

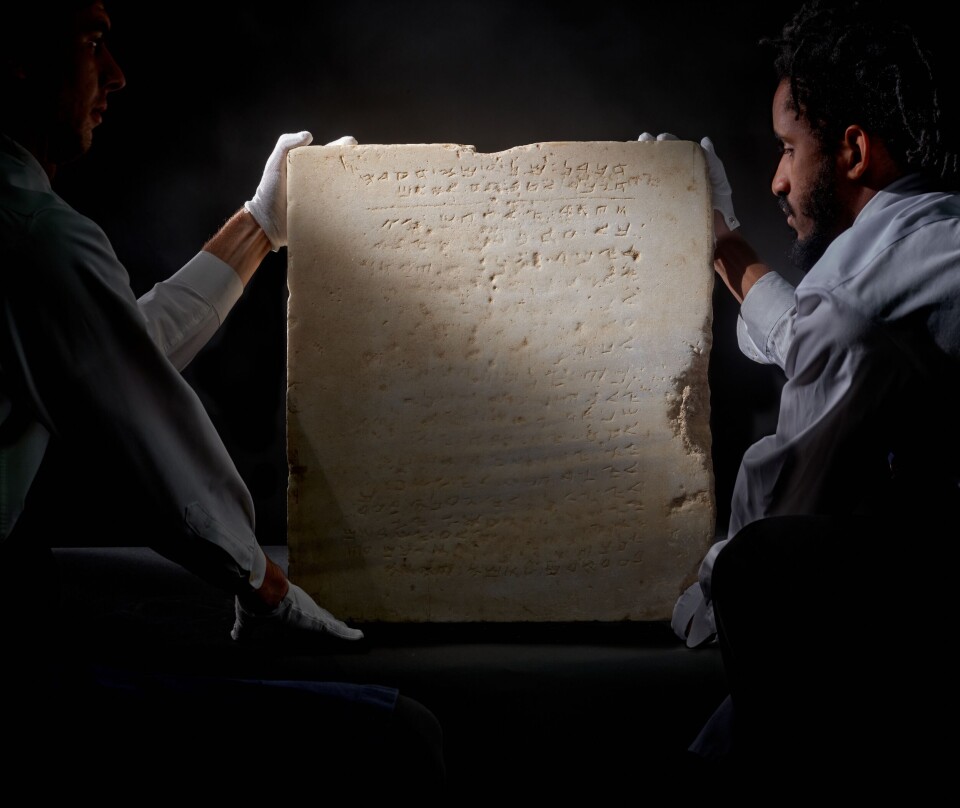

This stone tablet with the Ten Commandments was sold for $5 million, but is it authentic?

According to the auction house, it dates from sometime between 300 and 800 CE.

A stone tablet with the Ten Commandments was sold at an auction in New York on December 18. The final price was just over 5 million USD, according to the auction house Sotheby's.

The tablet is said to display a version of the Samaritan Ten Commandments: A version very similar to the one we know, but with an additional commandment about building a temple on Mount Gerizim. The stone tablet is believed to date from sometime between 300 and 800 CE, according to Sotheby's.

It was reportedly found in 1913 in what is now Israel. However, several experts, including a Norwegian professor, have raised doubts about both its age and origin.

Sotheby's initially estimated it would sell for between 1-2 million USD , but the final bid – including fees – was 5.04 million USD.

Red flags

American professor Chris Rollston has written a detailed piece for the Times of Israel about what he considers potential red flags. He uses the Latin phrase caveat emptor, meaning let the buyer beware.

“The origin story seems suspicious,” Torleif Elgvin tells sciencenorway.no. He is professor emeritus of theology, religion, and philosophy at NLA University College.

Confirming or disproving the authenticity of a stone inscription is extremely challenging.

Torleif Elgvin

Elgvin has previously worked on exposing fake Dead Sea Scrolls, which are early Jewish texts found in caves by the Dead Sea.

So what aspects of the tablet lead experts to question its authenticity?

No archaeological context

Both Elgvin and Rollston point out that this tablet was neither found nor documented in an archaeological context. As a result, nothing is known about the stone tablet before it was purchased by an archaeologist in the 1940s.

According to Sotheby's, the original seller of the tablet in the 1940s claimed it was discovered in 1913 during railway construction. After that, it was reportedly used as a door threshold.

“There were few Samaritans left in the area in 1913, but people knew that old inscriptions could be valuable,” says Elgvin.

If the stone tablet and its inscription were visible as a threshold stone, Elgvin finds it strange that no one had heard of it until the 1940s.

Rollston highlights the lack of photos or other evidence of the stone before the 1940s.

He also notes that the tablet is missing a commandment. He believes this makes the stone suspect, as such deviations can make copies more intriguing.

Elgvin believes there is a greater chance that this is a forgery rather than an authentic artefact, but he acknowledges that it is nearly impossible to confirm either way.

“Confirming or disproving the authenticity of a stone inscription is extremely challenging,” he says.

Forgeries?

The area that makes up modern-day Israel and Palestine has very long and deep historical roots. It has been of strategic and religious importance for thousands of years.

Ancient artefacts from this region are highly sought after. Elgvin explains that researchers in his field are often sceptical of artefacts that come from the open market, a suspicion that has grown stronger in recent decades.

“For example, you can find supposedly authentic jars from antiquity on the antiquities market in Jerusalem, but 99.5 per cent are fakes,” Elgvin estimates.

The New York Times has also reported on possible uncertainties surrounding the stone tablet. Brian Daniels, director of research at the Penn Cultural Heritage Center in Philadelphia, USA, points out that there are many forgeries from this part of the world. However, he acknowledges the possibility of the stone tablet being authentic.

“Maybe it's absolutely authentic, and this truly is a historic find,” he told the New York Times.

Torleif Elgvin states that there are many authentic artefacts from antiquity that have been dug up by grave robbers, but such finds lack archaeological context.

Dating

Elgvin also raises concerns about the dating of the tablet and its script.

Based on the kind of script, which Sotheby’s describes as paleo-Hebrew, the stone is dated to between 300 to 800 CE.

However, Elgvin argues that the text should instead be described as medieval Samaritan.

“This is an evolution of the ancient Hebrew script, which was used until the second century BCE,” he says.

Elgvin believes the script on the stone tablet dates from a later period.

“This places the tablet closer to 800 CE than 300 CE. Perhaps closer to 1000 CE,” he says.

If it is a modern copy, the script could have been replicated from other known Samaritan inscriptions, Elgvin suggests. Chris Rollston reviews several such inscriptions on his blog.

Sotheby's: Full support of its authenticity

A Sotheby's spokesperson responded to sciencenorway.no in an email addressing the criticism from Elgvin and Rollston. The full response can be found in the box below.

According to the auction house, they regularly conduct investigations and due diligence on the background of items before agreeing to sell them, and this was also done in this case.

———

Translated by Nancy Bazilchuk

Read the Norwegian version of this article on forskning.no

Subscribe to our newsletter

The latest news from Science Norway, sent twice a week and completely free.