Teaching children to think critically about health

Norwegian researchers have helped teach children in Uganda to be sceptical of purported health cures and treatments. It turns out that Norwegian children could use the same kind of training.

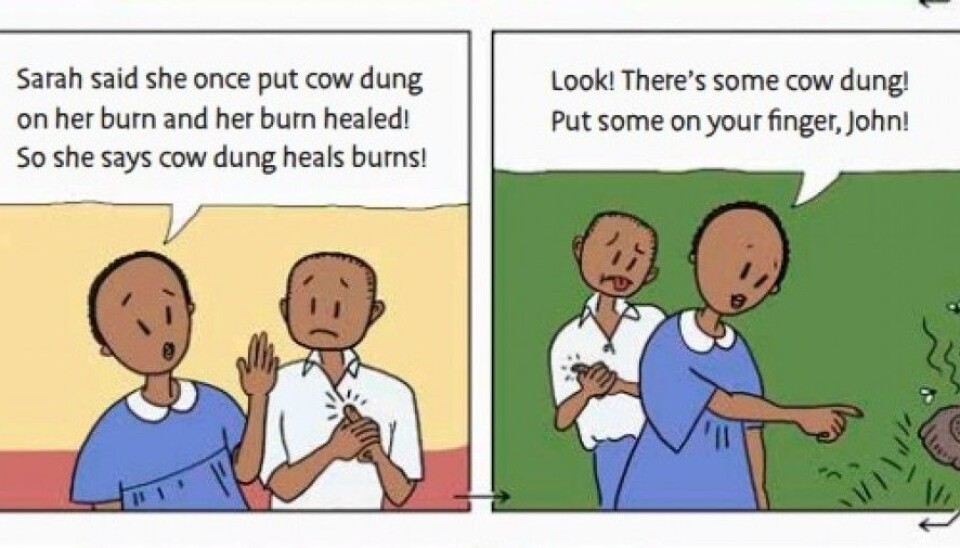

Cow dung is probably not the first thing that comes to mind when you are looking to treat a burn. But what about eating chilli peppers to treat gastric ulcers? Or using pesticides to treat self-diagnosed syphilis?

These may not be the first lines of treatment that you would choose, but things are different in Uganda.

“Many people use cow dung because it's so available. They think it can’t be harmful because it's natural,” says Allen Nsangi, a PhD candidate at the University of Oslo and Makerere University in Uganda.

Nsangi says these kinds of myths are a major problem in her home country. They are rooted in daily life and reasonably persistent. Many of the treatments have been used for generations. Others can be dangerous, she says.

Sometimes “people are advised to say no to cancer treatments and HIV medicines and use herbs instead,” Nsangi says.

Children first

One of the biggest problems relates to vaccines. Some Ugandans claim the HPV vaccine can lead to infertility. Some even think that the government's vaccination programme is a cover for population control. Therefore, many parents believe they are protecting their children when they say “no” to vaccines.

None of these claims is true, of course, but as myths they can be difficult to eradicate, especially in a society where people are not that well educated and their belief in authority is strong.

Nsangi believes the way to combat this problem is to start with children.

In association with researchers at the Norwegian Institute of Public Health, she has developed a teaching plan for young people to learn to think critically about health treatments.

And it works. As described in an article just published in online in the Lancet, children who have followed the study programme have become much better at sorting out the difference between myths and facts.

Lack of proof

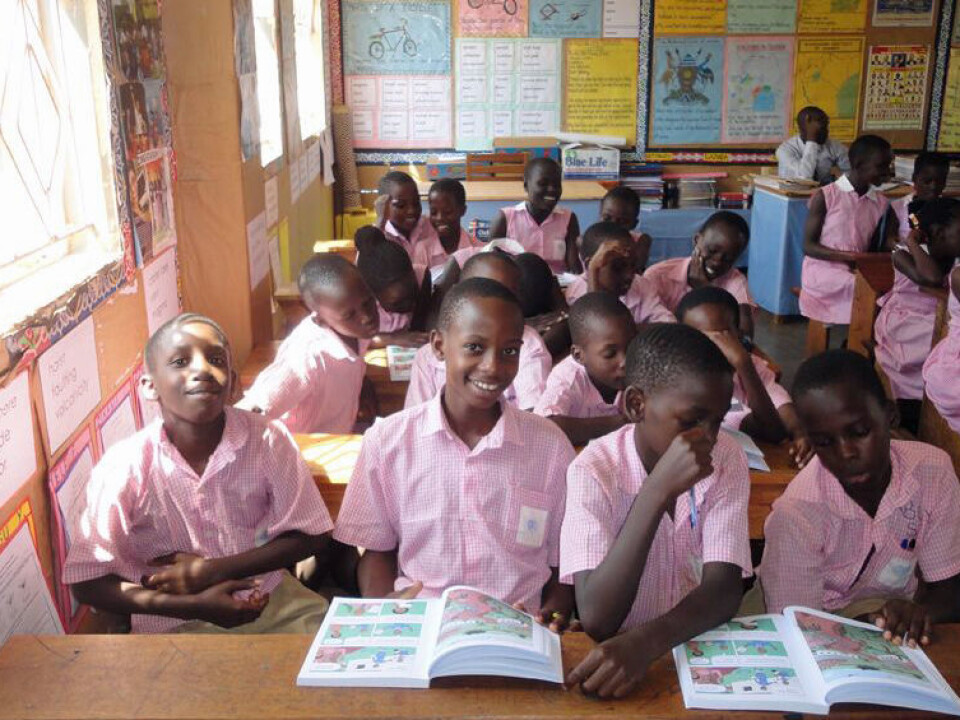

The researchers worked with 10,000 Ugandan schoolchildren from 120 schools, who were broken into two groups. One group received two hours of teaching a week over nine weeks with the designed programme, while the second group continued with their normal school programme.

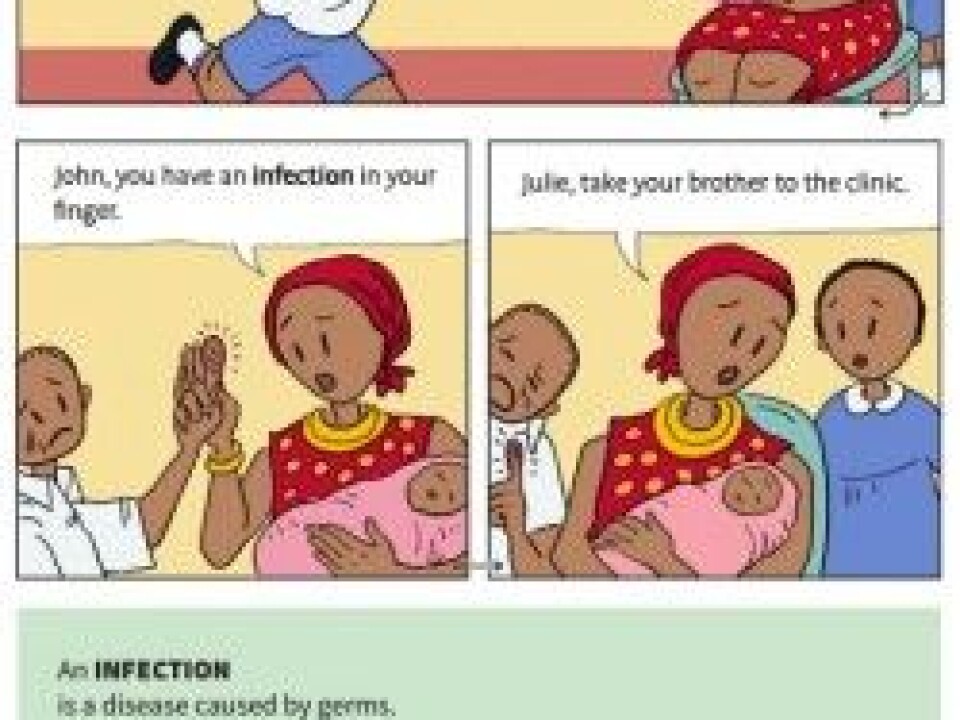

The 10-12 year-olds learned everything from the fact that all medicines can have side effects to the fact that you cannot trust one single individual’s experience with a treatment.

Afterwards, the researchers tested the extent to which the children responded correctly to 26 health-related assertions.

In the group that received training, seven out of ten (69 percent) students answered more than half of the questions correctly, while the group that continued in the normal educational programme got less than three out of ten (27 percent) of the answers correct.

In many cases, the correct answer was that it is impossible to know if a treatment works, because it had not been properly tested.

Norwegian students could also benefit

The researchers used comic books, conventional books and posters to teach schoolchildren to think independently.

The researchers worked with Ugandan schoolteachers to ensure that the children would understand 12 concepts that would help them be more critical about the statements they hear about health.

Norwegian students could also benefit from this kind of training, says Andrew Oxman at the Centre for Informed Health Choices, which is part of the Norwegian Institute of Public Health.

He helped create the teaching plan for the Ugandan students. He and his colleagues have spent ten years developing the plan and testing it in several countries, including Norway.

“Students are not taught to think critically about health in Norwegian schools,” Oxman said. “In many countries, schools focus too much on learning facts and too little on critical thinking and problem solving.”

Norwegian students are poor at evaluating statements critically, Oxman’s colleagues have discovered.

Only one-third of tenth grade students managed to summarize a statement about health practices from a news article and decide if it was reliable.

Oxman believes the knowledge the Ugandan students have gained is relevant in Norway, too.

“We have access to ever more information, through the internet and other media,” Oxman said. “There are a lot of old wives tales out there. Anecdotal evidence does not tell us what actually helps.”

Training teachers, too

Daniel Semakula is also from Uganda and was trained as a medical doctor. He worked on the project with Nsangi.

The researchers had convinced Ugandan teachers to let them into classrooms. It helped when they were able to point out old wives tales that teachers knew.

“They themselves had been victims of false health claims. One of the teachers had stomach ulcers and had been told to drink coal mixed in water every day for two years,” Semakula said. “He had bought a huge bag of coal. When he realized that this was a just a myth, he began to ask questions. Then he said to us, ‘There are so many people who believe in this craziness, how can we help you?’”

Health authority employees also believe these unsubstantiated myths, the two researchers said.

However, the researchers have managed to pique the interest of the health authorities and those in charge of the national school curriculum.

When the scientists return to Uganda to present their results, they hope they can encourage authorities to ensure that all schoolchildren are taught to think critically about health-related claims.

-------------------------------------

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no