Popular children's books from the 1950s contribute to Norway's special view of crime, study says

Thorbjørn Egner's stories about Cardamom town and Huckbucky forest are not just light entertainment for children. The narratives reinforce Norway’s ideals of crime and punishment, forgiveness and change, according to a study.

Professor of criminology Thomas Ugelvik recently won a prize for an academic article about Cardamom Town and Huckybucky Forest, two of Norwegian playwright Thorbjørn Egner's most famous books.

Huckbucky forest was published in 1953, and Cardamom town in 1955. But you'd be hard pressed to find a child in present-day Norway that does not know these stories and their songs by heart. Both stories have also in recent years been adapted to very successful feature length children's movies.

The two stories show the importance of being part of society and that not everyone has to be the same or behave the same, Ugelvik wrote in the article.

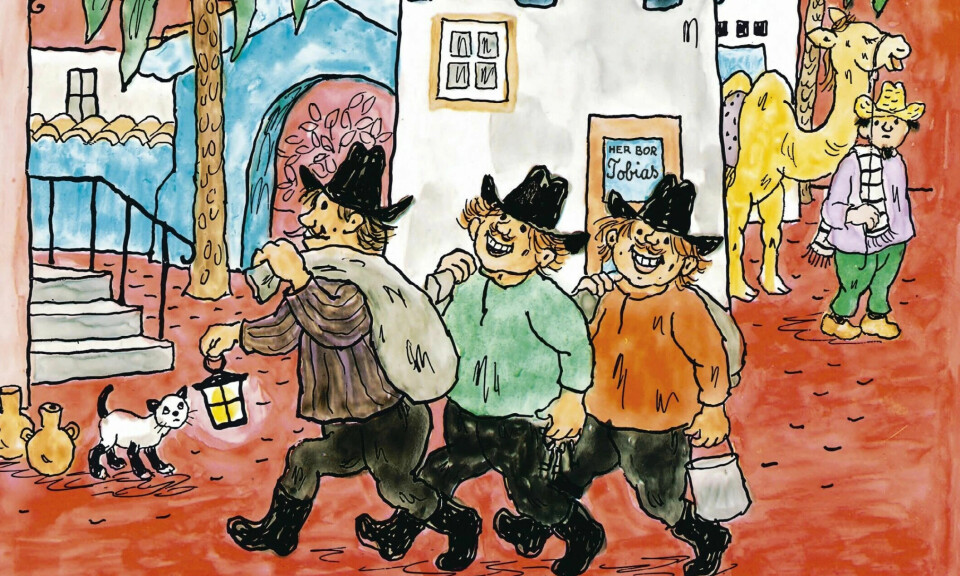

Three robbers, Casper, Jesper and Jonathan, live outside the town of Cardamom. They steal food, threaten people with their lion and kidnap a woman. Eventually they are caught.

Police chief Bastian immediately sets about rehabilitating them. The robbers are bathed and given a haircut, so that they look like "proper people". They get to hold a concert in the square with the town band. And in the end, each of them gets a job that suits their wishes and skills.

Punishment in a completely different way

This corresponds nicely with what international criminologists refer to as Scandinavian penal exceptionalism.

“The idea is that up here in the north we handle punishment in a completely different way than other countries. We are more humane,” Ugelvik said to sciencenorway.no.

Ugelvik is professor of criminology at the University of Oslo.

The three robbers in Cardamom Town are well looked after in prison. Police chief Bastian provides comfy beds and fine furniture. Mrs Bastian decorates their cell and cooks tasty food. It’s important that the robbers live well in prison.

“In Norway we have shorter sentences, better sentencing conditions and an equal relationship between those who work in and are jailed in our prisons,” Ugelvik said.

Return to the community

“We believe that it is possible for people to return to society after serving time,” Ugelvik said.

Marvin Fox in Huckybucky Forest is a violent criminal that the other animals are terrified of. He steals food and tries to kill his victims in the event of a protest.

But the fox also finds his place in the forest community after a period as a forced vegetarian. He first finds a loophole in the law, by stealing from a farm outside the forest. When this all ends in disaster for a bear cub, the fox uses his fox skills to save the cub.

The fox is included in the celebration and makes friends with everyone. He provides and cooks the food for the party.

Inspired by reading to his own children

The background for the scientific article about punishment, sentencing and rehabilitation in Cardamom Town and Huckybucky Forest grew out of Ugelvik’s own experience, reading the books to his children.

“I read the books over and over again. I wondered why these books are so popular 70 years after they were first published,” he says.

One possibility is that the parents know the stories so well. Another that the drawings and songs are so nice.

“I thought there had to be something more. Children today have so much on offer, yet these books live on, and new films are made. I wanted to understand the appeal they have for both children and adults,” he said.

Bad sometimes, but not always

The stories in the two books are quite similar. Some individuals behave badly, but eventually become part of the community.

“That is an important part of the appeal. It's a morality that works for the parents, but which the children also appreciate and can use in their own lives. Even if you behave badly sometimes, you don't always behave badly,” Ugelvik said.

This fits well with how Norwegians think about punishment and rehabilitation. Once criminals have finished their sentence, they can become part of society again.

Kristin Ørjasæter is a professor at the Norwegian Institute for Children's Books. She believes that Thorbjørn Egner struck a chord in our common humanity.

“He’s not clearly pointing a finger at morality, although there is plenty of morality in his books. If the moral is too clear in children's literature, then it doesn’t work so well. Children must be allowed to think for themselves. If I had been one of the robbers, what would I have done?” Ørjasæter said.

Who are the heroes?

Children seek recognition in children's literature. They build self-understanding and develop their identity through reading, Ørjasæter said.

“Children's literature sees things from the underside. The stories elevate characters who are at the bottom or outside of society, as with the animals and the robbers in Egner’s stories. The ideal of the hero is strong in children's literature, but who are the heroes in these two stories?” she asks.

It’s the robbers who perform the greatest heroic deeds. The petty thief Claus Climbermouse is the great charmer. Decent Sofie is scary, and the police chief doesn't arrest anyone.

Aunt Sofie did not get a place in Ugelvik's scientific article, but he also thought of her in his criminological analysis of Cardamom Town.

“Sofie marries one of the robbers. The research clearly shows that stable relationships and a better half are some of the clearest success factors in keeping offenders from committing new crimes,” says Ugelvik.

More offers today, greater diversity

Much has changed today, from the time when several generations read the same books.

“The media landscape is completely different. Children can choose what they want to read and watch in a completely different way than previously, not only with books, but also computer games and a multitude of other offers. Furthermore, children in Norway are also far more diverse than in Egner's time,” Ørjasæter said.

Thorbjørn Egner's influence on children must be seen in the light of the media landscape of the time and the Norwegian Broadcasting Corporation’s monopoly, she believes.

“Egner broke through on the radio's ‘Barnetimen for de minste’ (Children’s hour for the youngest), which the adults also listened to. Back then there was just one media channel. This made him very influential. His distinctive voice and all the songs made him particularly suitable for the audio medium,” Ørjasæter said.

From Barnetimen, the songs and stories moved to cassettes, animated films and theatre.

“The Riksteateret, a national traveling theatre group, has travelled far and wide with Egner's plays. And he set strict requirements for the scenography. This has led to us all having the same images in our heads,” Ørjasæter said.

Punishment and literature

For his day job, Ugelvik studies prisons and sentences, meaning, how criminals really experience prison.

“Children's culture is not seen as serious and important, but none of my colleagues have wrinkled their noses over this topic. I have been inspired to write further about how punishment, forgiveness and reintegration into society are described in other cultural expressions, such as novels and computer games,” Ugelvik said.

Ørjasæter says the view of children's literature has been divided, both among researchers and authors. Is it an artistic experience or pedagogy where children are supposed to learn from books?

“Today we say both. There is a close connection between positive values in society and children's literature,” she said.

Translated by Nancy Bazilchuk

Reference:

Thomas Ugelvik: Three burglars, a friendly police inspector, and a vegetarian fox: Scandinavian exceptionalism, children's literature, and desistance-conducive cultures. Nordic Journal of Criminology, 2022.

———