What did children really understand about the Covid-19 pandemic? Researchers examined children's drawings

We can learn a lot by studying how children draw, according to researcher.

Much of the research on Covid-19 has focused on masks, vaccines, and people moving from cities to rural areas. In a new study, researchers from Uppsala University in Sweden examined children's drawings from the pandemic.

The study was recently published in the journal Acta Paediatrica. The findings were also reported in a press release from Uppsala University.

The purpose? To understand how children perceived everything that happened during the Covid-19 pandemic.

But what can we really gather from a child's drawing?

“For children, drawing is a way of expressing emotions, dreams, and sorrow,” Bente Fønnebø says.

She is an associate professor at the Department of Early Childhood Education at OsloMet.

She has herself done research on children's drawings and published the book Å tegne sammen (Drawing together) in 2019. She thinks it is good to see new research in the field.

Covid-19 collection

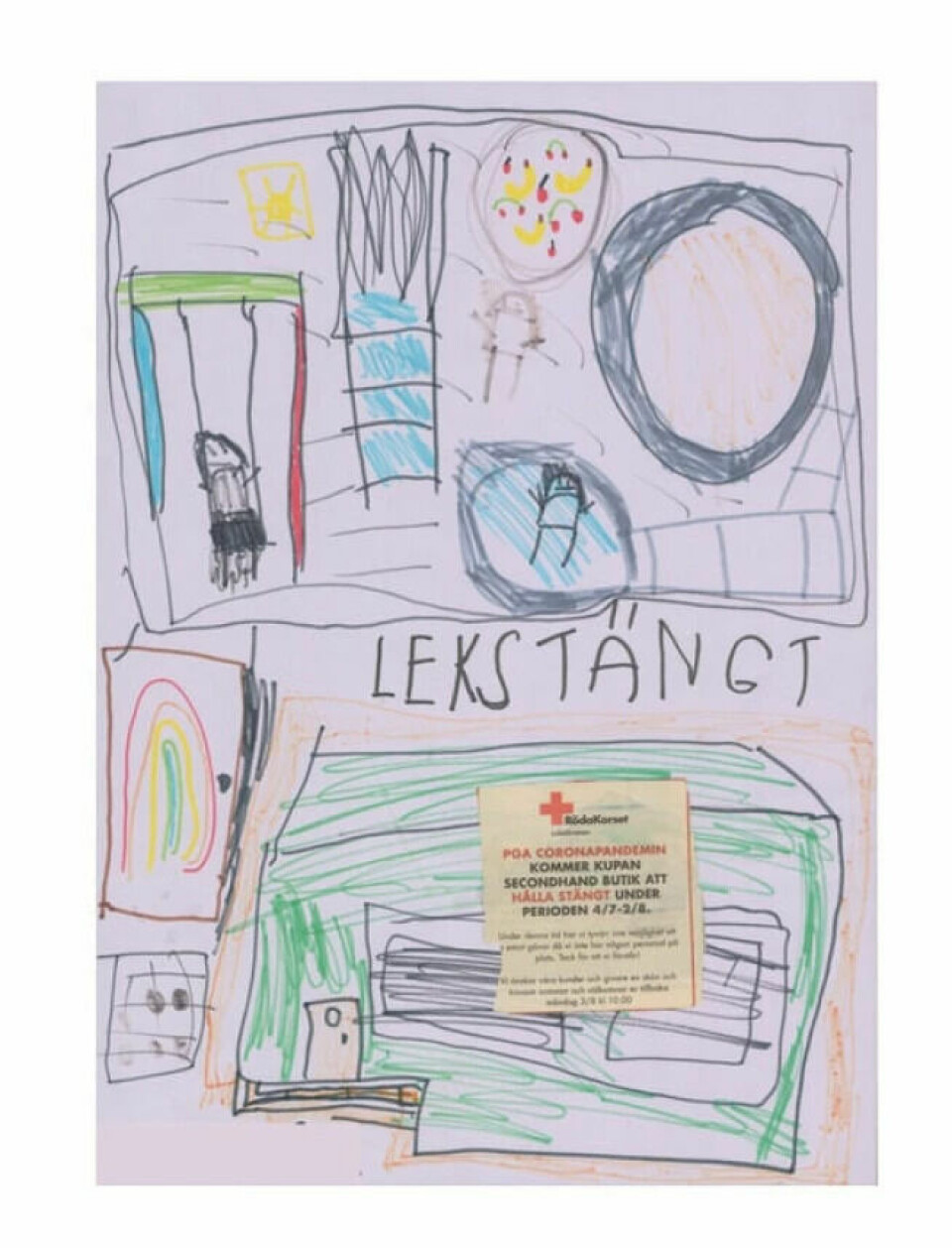

The drawings were borrowed from the Swedish Archive of Children's Art. They were drawn between April 2020 and February 2021. By that time, the archive had sent out a call to submit drawings to a separate Covid-19 collection.

They requested age, gender, location, and date. The children were also encouraged to describe their own pictures.

In total, nearly 1,300 drawings were submitted. Most were sent in by kindergartens, but there were also drawings that were submitted individually.

Around 100 of the drawings were made by children aged four to six. 91 of them had a description included, and these were analysed by researchers from Uppsala University.

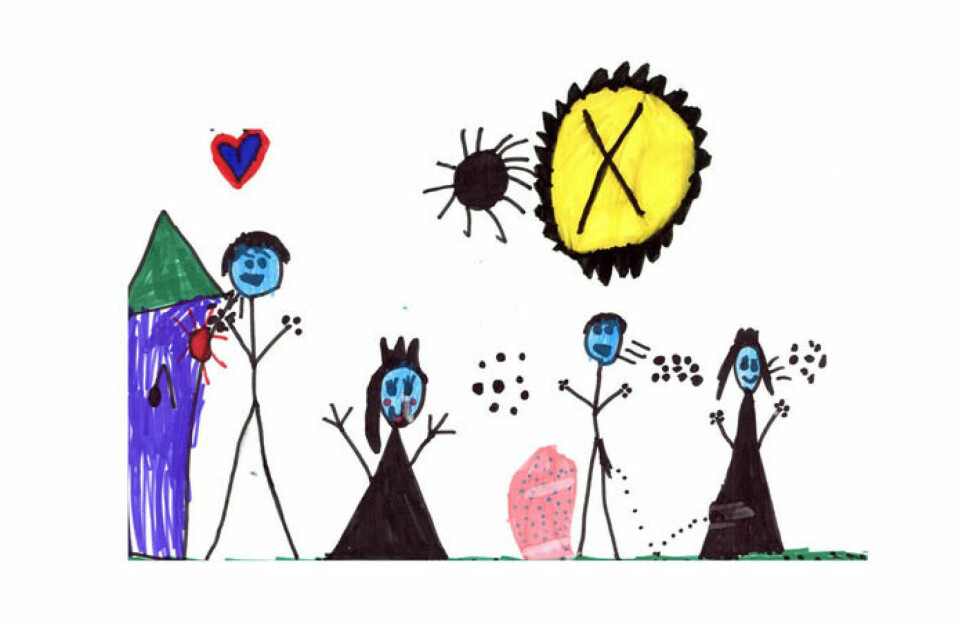

The children drew detailed pictures of illness, death, and canceled activities, the researchers summarise.

On adults' terms

The researchers believe that drawings are used too little when trying to understand children's understanding of different events.

In a situation where they are asked and have to respond verbally, the questions are often asked by an adult. The answer the children give must be within the language they master.

Drawing is actually protected by Article 13 of the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child, Fønnebø says.

Children should have the right to freedom of expression. And they should be able to express themselves in the way they are comfortable with. For example, artistically.

Therefore, it is important that the circumstances facilitate the child’s expression through drawing in a good and free way, she believes.

And everything must then be allowed to be drawn, whether it is bombs or flowers. Sometimes children may be encouraged to draw beautiful things or to leave out the dark colours. Fønnebø refers to this as a ban on drawing.

“We must not limit the child's ways of expressing themselves. The child may want to use darker colours to express anxiety,” she says.

Monster virus

In many situations, a child will struggle to express themselves in words. By drawing, they can tell something that goes beyond their vocabulary.

If it's not about a pandemic, it could, for example, be about the fact that the parents do not live together.

“It's typical for the child to draw a family picture where the parent who the child does not live with is the biggest. It is an expression of a desire for the family to be together,” Fønnebø says.

It may also be that the child draws themself together with a dog because they want a dog. Children start with this as early as three or four years old, she says.

In their study, the Swedish researchers saw that the children often drew a virus as very large. Some of the children described it as "a monster".

The process is important – not just the finished drawing

“Research methods are interesting. The methods you choose can have a lot to do with what you find out,” Fønnebø says.

And the methods have changed a lot in recent decades.

“30 years ago, the most common method was to analyse end products,” Fønnebø says.

In other words, researchers were mostly concerned with the finished drawing. There was not much talk about the drawing process and the situation.

“Today, it’s just as much about the drawing situation the child was offered,” she continues.

Different situations give different prerequisites. Like when the child gets to draw with other children. Then humor and joy can influence the result.

The preferred method relies on the child being more free to choose what the drawing should be about. In this study, the children were given a prompt, or a kind of task, to draw something related to Covid-19. In this way, the children were to some extent controlled by adults.

Calls for more varied drawing

Drawing is not only important for children to express themselves. It also has a lot to do with the child learning to master hand-eye coordination, while also being an exercise in concentration, says Fønnebø.

She worries about what technological development is doing to that.

“Actually, I am worried, because having concrete contact with materials inspires children to express themselves,” she says.

She says that digital tools such as stories and photography can inspire drawing.

“So it's not either-or. But you can see that drawing in kindergarten often involves sitting at a table with a small sheet of paper,” she says.

She calls for more variation in drawing.

“Why not hang large veneer panels on the fence in kindergarten and let children draw on them? Or roll out cardboard and let the children use their whole bodies to draw?” Fønnebø says.

———

Translated by Alette Bjordal Gjellesvik.

Read the Norwegian version of this article on forskning.no

References:

Sarkadi et al. Perceptions of the COVID-19 pandemic as demonstrated in drawings of Swedish children aged 4–6 years, Acta Paediatrica, 2023. DOI: 10.1111/apa.16706