Mountain plants crowd at the peaks

A warmer climate is enabling hardy lowland vegetation to ascend mountains and thrive at higher altitudes. When they can’t get any higher, they’ll crowd together on peaks.

Denne artikkelen er over ti år gammel og kan inneholde utdatert informasjon.

Norwegian mountain flora is engaged in a drama between old settlers and fresh newcomers. Frugal mountain plants have long clung to their inhospitable domains just below snowcaps.

But the heat is on. Lowlanders have discovered new digs with a better view and whoops, there goes the neighbourhood.

Intrepid plants are eating their way up the grade. They seek more nutrition and are finding it. A warmer and wetter climate is giving them what they need, 40 to 100 metres higher than they could reach 80 years ago.

The mountain’s robust veterans are being swept aside by the green lowland wave. The race up the slopes is on. They’ll meet at the peak.

Sociology for plants

Early botanists conducted thorough studies of plant communities in the Norwegian mountains. They noted every species they could find in small, delineated areas.

“It’s called phytosociology, or plant sociology, and it was an important branch of botany in Norway 50 to 100 years ago,” explains Jutta Kapfer.

She did the fieldwork in the mountains as a research fellow at the University of Bergen, but is now a researcher at the Norwegian Forest and Landscape Institute.

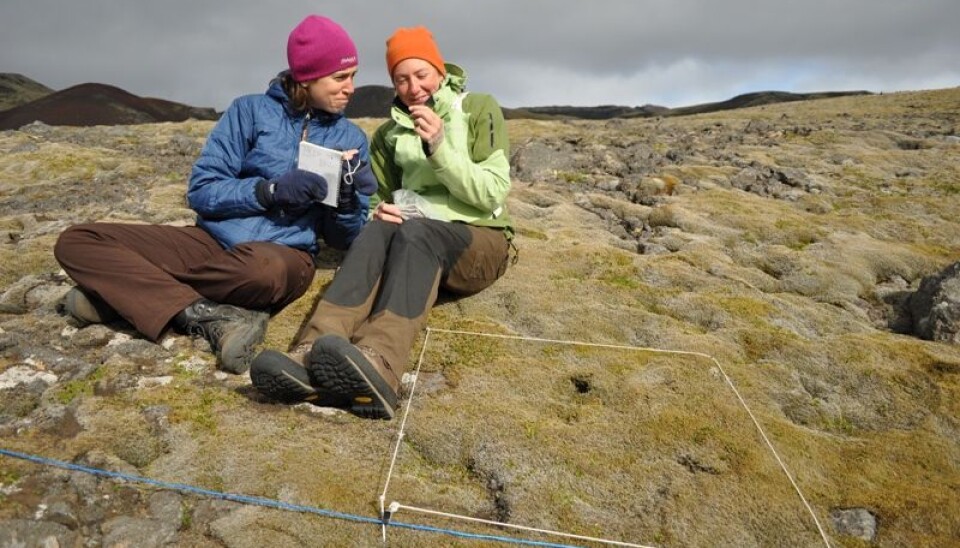

The fieldwork was done at approximately the same sites as the old botanists. Kapfer compared the current situation with information in old notebooks, up to 80-year-old surveys of phytosociology.

“The challenge with these comparisons is that researchers in the old days didn’t write down exactly where they made their observations,” she says.

This poses a problem for example at Sikkilsdalen in the mountainous region of Jotunheimen. Botany Professor Rolf Nordhagen charted the area from 1922 to 1932. He had no GPS, of course, and didn’t always know precisely where he was.

Returning to the same spot

For Kapfer and others who chart changes in vegetation with old phytosociological studies as their point of departure, it’s important to use the same procedures in the same spots as accurately as possible.

Significant microclimatic differences can be found just metres apart, for instance at warm or cold spots in the terrain. These can camouflage the long-term changes that Kapfer and her colleagues are investigating.

Void of vegetation

Kapfer has also studied plants on Jan Mayen, a geologically young and volcanic Norwegian island 600 km northeast of Iceland.

“In many places the volcanic ash is still barren and completely void of vegetation. Sometimes we had problems finding the plants we wanted to study,” she says.

Despite that, Jan Mayen is in many ways an Eldorado for plant ecologists.

“Humans and animals haven’t disturbed the vegetation here. All the changes that occur are due to other key factors, such as the changes in climate.”

Kapfer and her fellow pair of researchers studied grasses and the plant dwarf willow (Salix Herbacea), often called the world’s smallest woody plant species, maximum five centimetres tall.

And they observed changes. More dwarf willow and grasses had set root on Jan Mayen and they found fewer of other plant species. A changing climate is the most likely suspect.

Climate is the key factor

“The snowcap levels in the mountain regions of Norway have risen and spring is coming earlier. The growth season for plants has become longer and they can grow larger and further up the mountains, where it was previously too cold for them,” explains Kapfer.

But the climate is no universal explanation. Traditionally there were more livestock browsing in Sikkilsdalen in Jotunheimen. Among them were Døle horses. Wouldn’t their browsing change the vegetation?

“Our studies show that changes in browsing intensity probably have little or no impact on the changes in vegetation we’ve observed in the area.”

But the results differ. Other studies show that browsing and various changes in agricultural practices have indeed had a large effect on changes in vegetation.

And these changes can counteract or camouflage the impacts of a warmer climate, according to Kapfer’s doctoral thesis.

Dressing up the mountain

Trees are in the process of cladding mountains and bogs up here in the North. Newer and more accurate studies will show the tendencies even clearer as the years go by.

“If the current trend continues, bushes will cover increasingly more Arctic areas and trees will follow them,” says Kapfer.

“Distinct mountain species can disappear and more lavish lowland species will take over. They will keep climbing until they can get no higher. Then they’ll all get together – at the top.

Reference:

Jutta Kapfer: Last-century vegetational changes in northern Europe. Characterisation, causes, and consequences. Doctoral dissertation, University of Bergen 2011.

Translated by: Glenn Ostling