New study: The Black Death did not kill half of Europe’s population

An international research group has found that the pandemic affected different areas of Europe differently. Norway may have been hit hard.

The Black Death ravaged Europe in the years around 1350.

It became the most notorious pandemic in human history, although the plague and other infectious diseases struck Europe a number of times before and after.

A common assumption has been that the Black Death took the lives of half of the population — both in Norway and in the rest of Europe.

Did 65 per cent of the population die?

Some estimates — based on historical sources —suggest that as much as 65 per cent of Europe's population died.

The researchers behind the new study, published in the journal Nature Ecology and Evolution, believe this may be an exaggeration.

Erik Daniel Fredh is a researcher at the Museum of Archaeology in Stavanger and the sole participant from a Norwegian research institution in this international study.

“We find that the Black Death was completely devastating for some regions in Europe,” he says to sciencenorway.no. “But we find little or no impact in other regions.”

People lived by farming

Researchers from several European countries were involved in this new, original approach to estimate how serious the Black Death really was for Europe's population in the period from 1346 to 1353.

About 670 years ago, a clear majority of Europe’s population supported themselves by agriculture. Between 75 and 90 per cent of the population at that time lived in villages.

If many of these people died at the same time, it should be possible to see clear traces of this, in the form of reduced amounts of agriculture-related pollen, especially cereal pollen.

Instead, the researchers predicted that birch and other tree pollen would appear as these species recolonized the formerly cultivated landscape.

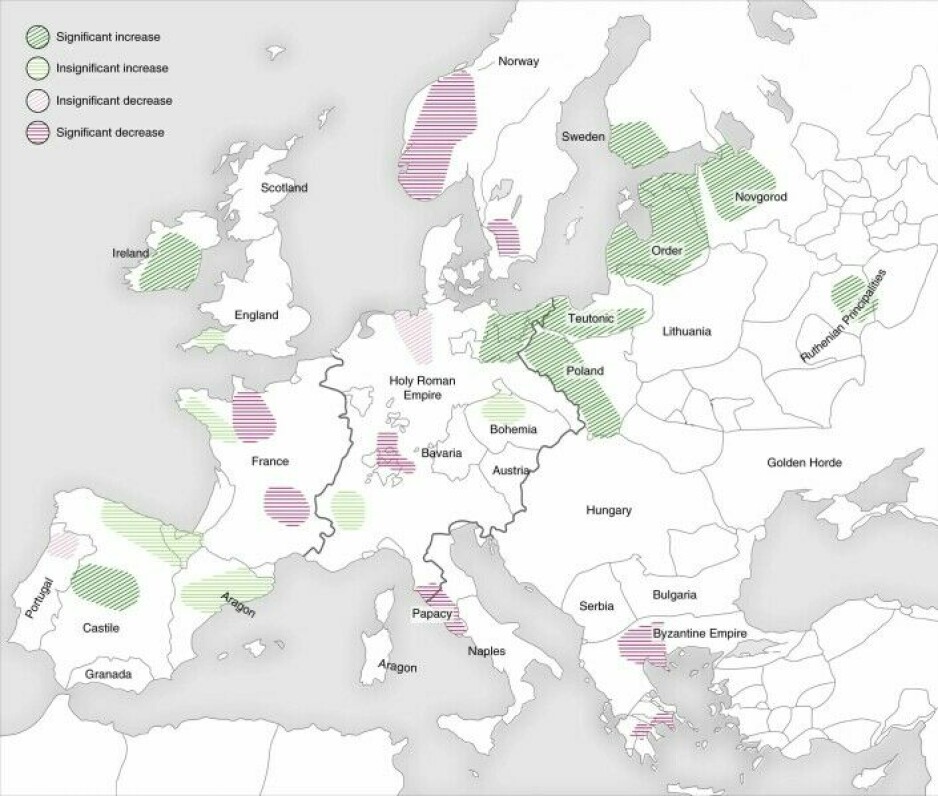

This is exactly what the researchers found. But they didn’t find it everywhere.

Just seven of the 21 areas in Europe surveyed by the researchers showed clear evidence of this shift. Norway was one of them.

Scandinavia hard hit

Every year, plants release enormous amounts of pollen, much of which is preserved in wetlands and lake bottom sediments.

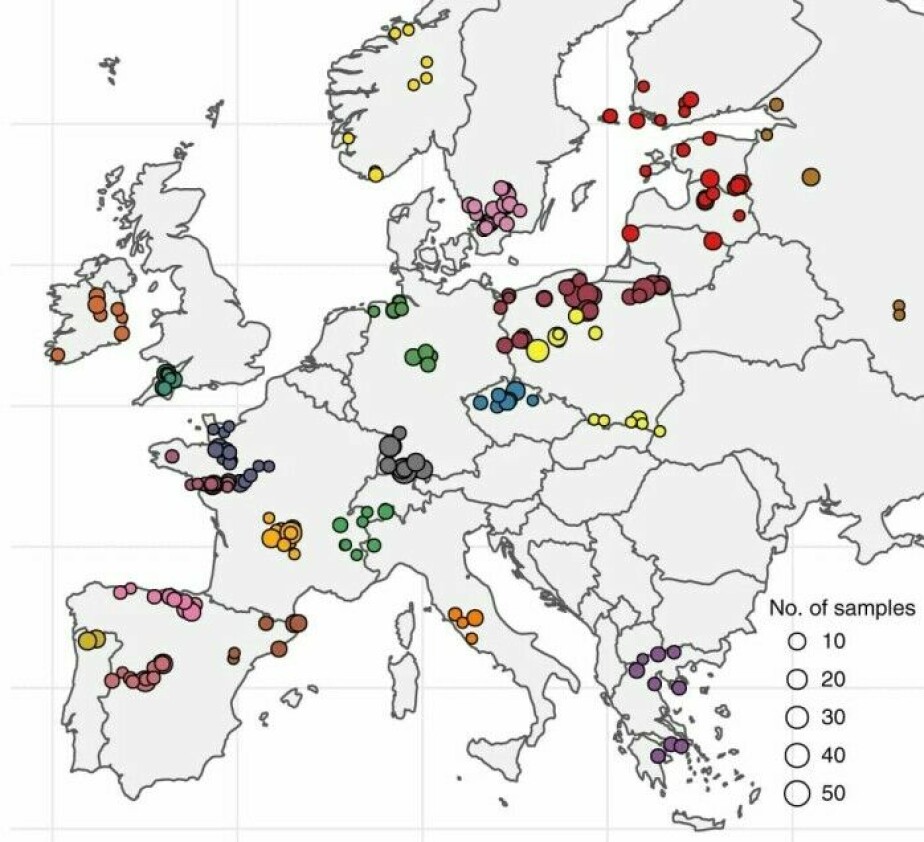

Researchers collected 1,634 pollen samples from bogs and lakes, spread over 21 regions in 19 European countries.

Using a technique called carbon dating, the researchers were able to date the pollen samples they used in the study to the years just before and after the Black Death.

“We saw no overarching pattern for how the Black Death affected European societies,” Fredh said to sciencenorway.no.

In some parts of Europe — such as Eastern Europe, Spain, Ireland and parts of Central Europe — researchers hardly found any evidence in the form of agricultural declines from history's worst pandemic.

In some places, agriculture even flourished during the Black Death, the researchers found.

In large parts of Norway and the rest of Scandinavia, however, many farms were probably abandoned and the land was no longer cultivated.

Paleoecology

The Stavanger researcher and his European colleagues believe that if we are to have a more reliable determination of the impact the Black Death had on society, we need to use more than just written historical accounts.

Paleoecologists such as Erik Daniel Fredh use pollen and other organisms from the past to say something about the history of the Earth and humans.

This international study is the first time the discipline of paleoecology has been used to say something about a dramatic historical event such as the Black Death.

———

Translated by Nancy Bazilchuk.

Read the Norwegian version of this article on forskning.no

Source:

A Izdebski et al.: “Palaeoecological data indicates land-use changes across Europe linked to spatial heterogeneity in mortality during the Black Death pandemic,” Nature Ecology and Evolution, February 2022.