Tracking the cuckoo's nest

Squatting in other birds' nests and kicking out legitimate chicks might not give the cuckoo any prize for 'best house guest', but as the only brood parasite in Northern Europe it is a good indicator for the current state of affairs for several bird species.

Denne artikkelen er over ti år gammel og kan inneholde utdatert informasjon.

Researchers at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU) are gathering a large database of Cuculus canorus and its 20 subspecies across Europe – so far with approximately 45,000 entries.

The database includes a comprehensive range of registrations, research reports, old and new publications on cuckoos, blood sample analyses from different subspecies, and a raft of information on host species – such as who they are, where and when they breed, their diet, how many eggs they lay and when the eggs hatch.

18th century cuckoo records

There is a rich mine of historical information on the cuckoo, with the oldest research records stretching back to the late 18th century. When museums started collecting cuckoo eggs some decades later, egg collectors carefully noted date and site of both cuckoo and host eggs – records that are still available today.

This gives researchers a great deal of material to explore the cuckoo's host preference, both when it comes to species, geography and time period, in order to analyse how the cuckoo has adapted to a changing world and new host species.

DNA from egg shells

“Using tiny samples of old egg shells, our molecular biologist can now also extract DNA information about both the cuckoo and the host species,” says Bård G. Stokke, a conservation biologist at NTNU.

“This will give us valuable genetic data on how cuckoo subspecies have evolved and differences in their genetic makeup.”

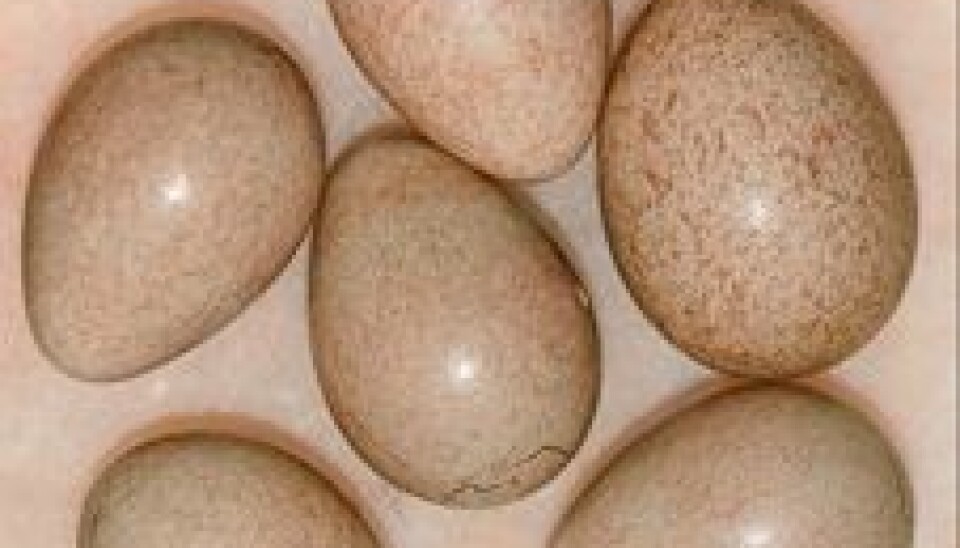

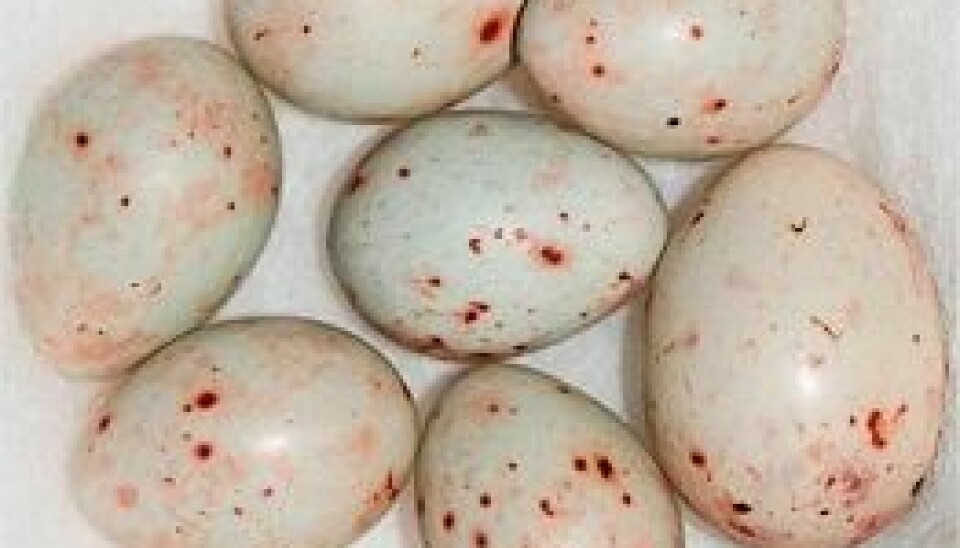

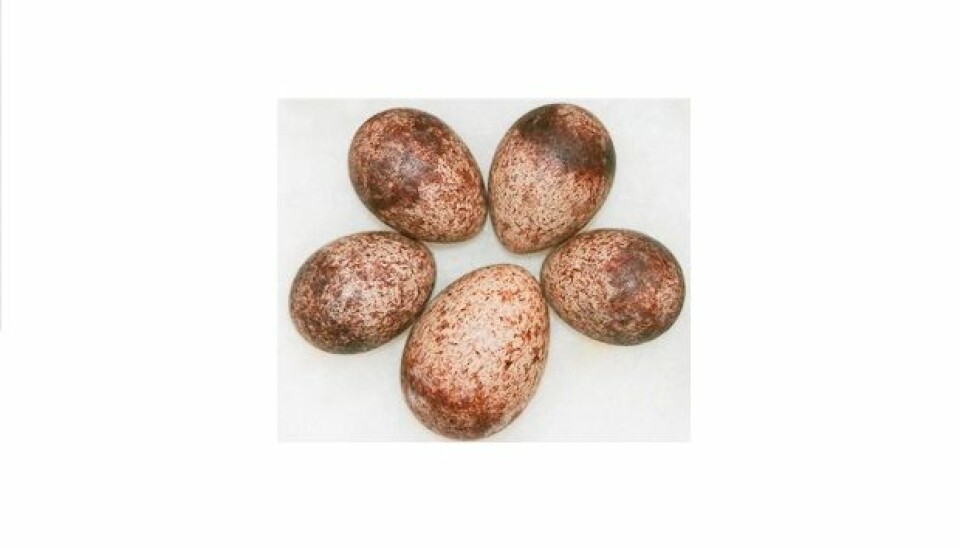

Cuckoos belonging to the same subspecies use the same host species. The cuckoo egg usually imitates the host species' own eggs, so it can pass off as one of their own without the bluff being called and the egg rejected.

“One of the most interesting aspects is to explore whether there actually are genetic differences between subspecies,” says Stokke.

“Are they always mating with individuals from the same subspecies? Previous research has indicated that egg colour is passed on from mother to daughter. But perhaps the male also has a role in this, as preliminary findings suggest? We are now mapping family relations using DNA from blood samples to see how this is connected.”

Tracking migration

As well as mapping the number of subspecies and monitoring populations, the researchers will also be tracking cuckoo migration by tagging the birds with tiny satellite transmitters.

By combining historical records and modern technology, the researchers hope to paint a picture of how the cuckoo adapts to a new environment. If the host species disappears from the area, is the cuckoo subspecies doomed to decline, or does it manage a gradual transfer to a new host? A warmer climate might also trigger earlier breeding for host species, leading to knock-on effects for the cuckoo.

In a changing world, the cuckoo can provide many answers – not only for its own kind, but also for a wide range of host species.

-------------------------------

Read the full story in Norwegian at forskning.no