Here’s how to get rid of black spots on the apples in your garden

You can do a lot to get rid of apple scab on this summer’s apples, but you have to act now, in May.

While commercially grown apples have smooth, beautiful surfaces, the apples in your garden may not look nearly as healthy.

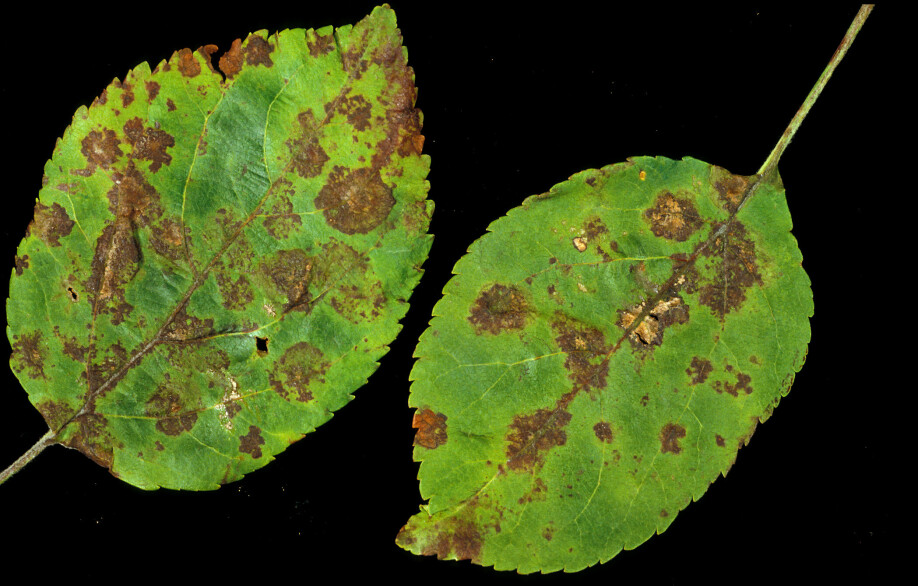

The apples in many people’s gardens are marred by large or small black dots.

This is called apple scab.

The risk of infection from this disease is highest now, in May and early June.

“Scab on apple and pear trees is very common in Norway and is caused by a fungus,” says Professor Arne Stensvand at NIBIO, the Norwegian Institute for Bioeconomy Research, to sciencenorway.no.

He pours a bag of dry, brown-grey leaves onto the desk in his office in Ås, outside of Oslo.

“The fungus is difficult to get rid of, but there is actually a lot you can do to reduce the scab on your tree,” he assures.

Overwinters on the leaves on the ground

If your trees had a lot of scab last year, they will probably get it again this year. The amount of potential infection sources, called the infection pressure, has a lot to say about whether this year's apples are affected by the fungus.

And the fungal infection that causes scab overwinters on the leaves that fell from the tree last fall.

Stensvand points to the leaves on the table:

“The fungal spores are formed in scab-infected leaves from last year and can spread in the air and reach the new growth on apple trees. The spores spread particularly during the period around flowering,” he said.

When it rains, the spores are released, and the wind blows and swirls the spores up from the old leaves under the tree. That causes the fungal spores to fly up into the air and land on new leaves, shoots, flowers and later, fruit.

Then the tree’s fate is sealed.

Remove the leaves from the ground

To prevent this, you should rake old foliage away from under your trees. That reduces the infection pressure, says Stensvand.

At the end of the summer, the spores stop spreading from the old leaves. You can put these leaves in the compost, but cover them, so that the spores won’t be released into the air and spread, he says.

Can come from your neighbour

Unfortunately, it won’t help much if you take care of your lawn and remove infected leaves if your neighbours are a bit lax with clean-up.

“The leaves fly around and the spores spread in the prevailing wind direction,” says the professor.

There’s not much you can do about this.

But the spread of spores is not everything. There are a few other factors that come into play that you can influence.

Must be moist

In order for the fungus to be able to infect the tree, the plant tissue must be moist for several hours at a time. Rainy weather when the apple tree is blossoming consequently makes the tree very prone to fungal attack.

“How many hours the fungus needs to attach depends on the temperature. If it is 20 degrees Celsius, the fungus has to have at least six hours of moisture on the tree to establish itself,” says Stensvand.

If it is colder, the fungus needs more time to get established.

Prune so that the branches aren’t too close together

The leaves also stay moist longer if the branches are too close and touch each other.

“That’s why it’s important to thin out the branches. Prune the tree so that each branch hangs as freely as possible before flowering,” says Stensvand.

Then the leaves dry faster, and it becomes more difficult for the fungus to establish itself.

Stensvand is also a professor at NBMU, the Norwegian University of Life Sciences.

He is from Hardanger, is known for his fruit growing and in took a doctorate on the topic of scab on fruit trees back in the day.

Now he's happy to travel around the country and tell farmers about various fungal diseases on trees and shrubs. He also gives lectures for garden groups.

Scab warnings

Researchers have created something like a forecasting service for apple scab and other pests and diseases on berry bushes and fruit trees. It’s also open to private individuals.

The website can be found at Vips-landbruk.no.

The forecast shows how many spores are spreading at different times of the season and day, and the risk of infection.

Users can click on the fruit, pest and nearest measuring station of interest.

Air temperature, precipitation and leaf humidity are parameters that determine how strong the attack will be.

Stensvand has studied which conditions are epidemiologically favourable for infection, in collaboration with colleagues in other countries.

The notification service also contains information about other plant diseases.

Robust varieties

Infection pressure, climatic conditions and the varieties' resistance are decisive for how little or much apple trees are affected.

Some apple varieties are more resistant to apple scab than others. If you want to buy a new apple tree, it’s a good idea to check how resistant the variety is.

“Unfortunately, it’s often true that if a variety is strongly resistant to one disease, it can be less resistant to other diseases,” Stensvand said.

Discovery and Aroma are two varieties that are very resistant to scab, he says.

“But don’t buy Gravenstein and Summerred,” Stensvand said.

Get permitted pesticides

There has been greater focus in recent years in Norway on limiting the use of pesticides and chemicals as much as possible.

Most chemical pesticides have been banned for private individuals for use outdoors. However, farmers and other professional practitioners are still permitted to use certain chemical agents.

“As far as I know, there is no approved preparation that hobbyists can use. Professionals have a lot of options,” Stensvand said.

The substances that are permitted for private individuals and farmers’ use for different plant diseases can be found at plantvernguiden.no (in Norwegian). This website has been prepared by NIBIO in collaboration with the Norwegian Food Safety Authority.

Norway largely follows the EU regulations on permitted chemical agents.

Translated by Nancy Bazilchuk

Reference:

H. Eikemo et.al.: Evaluation of six models to estimate ascospore maturation in Venturia pyrina. Plant Disease, 2011.

———

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no