Serving up edible kelp to Michelin restaurants and supermarkets

An entrepreneurial company called Seaweed Solutions is now harvesting more than 100 tonnes of nutritious kelp from a seaweed farm off the coast of central Norway. The seaweed is being sold to food producers in Europe. “This industry will be big,” says an independent researcher.

Round seaweed farm cages crowd the waters in the sea off the island of Frøya, on mid-Norway’s Trøndelag coast. This is where one of the world's largest producers of farmed salmon is located. And now the farming and cultivation of other marine species is really gaining momentum.

It isn’t always easy to spot all this production, though. Colourful boat buoys scattered across the sea signal that something is happening below the surface — the Seaweed Solutions kelp farm.

Seaweed Solutions is based in Trondheim and has been working for ten years on the development of kelp cultivation as a new industry. The goal is to grow kelp on a large scale and become a leading exporter of climate-friendly food, feed and bioplastics in Europe.

Recently, the British business newspaper Financial Times published a video about the entrepreneurial company, under the title Sustainable Crop for the Future.

Seawater and sunlight

The company carries out all stages of production itself, from sowing and cultivation to harvesting and sale. Brown algae kelp can be grown like any other plant, except that green fields are replaced by blue sea.

“It needs no inputs other than clean seawater and sunlight,” Jon Funderud, the company’s CEO, said to sciencenorway.no.

Since their start in 2009, the company has carried out several pilot projects with kelp cultivation in the sea at Inntian, outside of the municipal centre of Sistranda on Frøya. They have painstakingly tested all stages of growing sugar kelp and winged kelp, both of which are brown algae.

The project really took off in 2019, when the company received NOK 16 million in support from Horizon 2020, The EU Framework Programme for Research and Innovation, to reach out to the market with the product.

“It also made it easier to get private investors to invest money,” says Funderud. He is a marine biologist from NTNU, and took his master's degree in integrated farming of kelp and sea cucumber.

This industry will be big

“I am convinced that this industry will be big,” says Dagbjørn Skipnes, a senior researcher at Nofima, an applied research institute focused on fisheries, aquaculture and food research. Seaweed as human food is one of his research topics.

The global population is growing, with an associated increase in the need for food, while arable land is in short supply. The pressure is on to grow more of the world’s food in the sea. That’s why Nofima is studying the nutrient content of new raw materials that can be grown in the sea. The goal is to find optimal methods to process raw materials.

He believes it’s time that the Nordic countries follow Asia’s lead in using kelp for food.

“Seaweed cultivation outperforms salmon farming in aquaculture worldwide. Asia in particular is a major producer,” says Skipnes. Seaweed is widely used in Asian cuisine.

Along the Norwegian coast, kelp has long been harvested as fertilizer and supplement for animal feed. But as food, kelp is relatively new in Norway.

“There are very few downsides to using kelp for food. It contains fibre, minerals and acts as a salt substitute,” says Skipnes.

Vertical forests

Seaweed solutions is currently harvesting several tonnes of kelp to be exported in large frozen blocks to food producers in Northern Europe.

“We sow kelp seedlings inside the hatchery in mid-winter, where they grow attached to ropes. Then we lower the ropes horizontally in the sea, so that the kelp grows like a vertical forest,” Funderud said.

In collaboration with SINTEF Ocean, among others, they have studied how to best treat the young seedlings for them to grow optimally.

“They have to be kept cold and dark in the beginning, because conditions have to be similar to natural growth in the sea in winter,” he said.

Harvested at 2 metres long

Starting at the end of April until May-June, the kelp is ready for harvest.

“Then it has grown to be one to two metres long, which is pretty formidable growth for four months,” Funderud said.

The company avoids unwanted hitchhikers or growth on the seaweed by harvesting it as early as May-June.

The harvest also requires that the kelp be cut in the right place, and that it is rinsed well. The company has collaborated with SINTEF Industry to come up with the best possible processing techniques.

Served at Michelin star restaurants

Seaweed Solutions delivers the fresh kelp to a food company called Hitramat, which packs and freezes it as a raw material in 10 kilo blocks.

The kelp is mostly exported, but is also used in high-end restaurants in Trondheim, such as Credo and To Rom og Kjøkken. Credo uses only local ingredients and has one Michelin star.

“We focus mostly on major players in the European market, and sell it as a raw material for vegetarian products,” Funderud says.

They now export to food producers in the Nordic countries, Germany and the Netherlands.

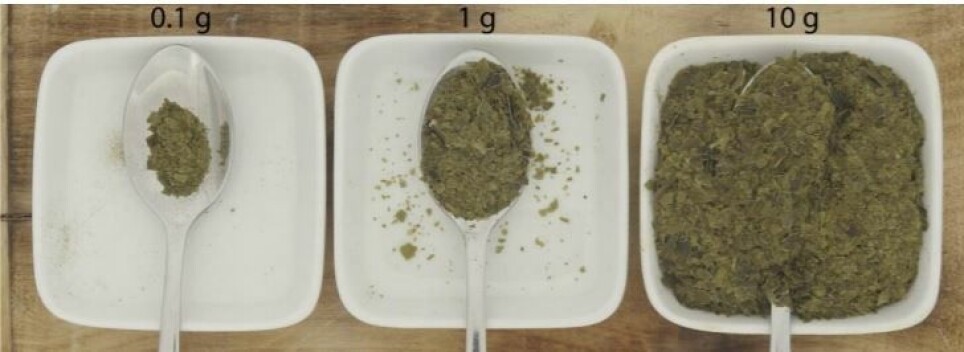

The company isn’t focused on direct sales to consumers in grocery stores just yet. Another option is to sell the kelp as a dried product.

“But currently this isn’t profitable enough because it is too resource-intensive,” Funderud said.

Beer with kelp won the prize

Seaweed Solutions has also delivered dried kelp to a local, small-scale beer producer Bryggeriet Frøya. The brewery recently won a gold medal in the European Beer Challenge for a type of beer it called Furia, which uses kelp as a flavouring, according to an article in the local newspaper, Hitra Frøya.

In the long run, kelp could become an ingredient in everything from crispbread and pesto to aquavit and spices.

Bioplastics are also a market the company is trying to enter. The bioplastic market involves using natural substances to make products that have previously been made of plastic — such as straws.

Growing interest in sustainable food

Currently, the company has only six permanent employees, and hires seasonal workers during the harvest.

Their current capacity is 100 tonnes, but they’re expanding the farm to be able to produce 500 tonnes of kelp, over an area of 19 hectares.

“We think the timing is just right, because there’s growing interest in sustainable food like this among chefs, vegans and vegetarians,” says Funderud. “The market for vegetarian products is growing by 30 per cent a year. We are now upscaling to meet the growing demand.”

Kelp is rich in fibre, minerals and iodine, which makes it especially interesting for vegans.

Kelp farming is also sustainable, in contrast to many other types of food production which can involve deforestation. In contrast, growing kelp contributes to CO2 capture and produces oxygen.

A seaweed forest is like a huge underwater rainforest, which contributes positively to the climate.

Demanding application for Horizon 2020 funds

Seaweed Solutions received research grants from the EU of several million Norwegian kroner in 2018. But that was only after several applications without success. The application process was demanding and extensive, Funderud said.

“Horizon 2020 and other EU programmes have become very competitive. We got approval for our fifth application. Considering how small the chances of being given a grant are and how much work the application requires, I don’t know if I would recommend that anyone apply,” he said.

“But it’s clear that once you are approved, it’s a source of fantastic support for a small company like ours,” he said.

He said other entrepreneurs should consider whether it would be better to spend the time they’d have to use on a grant application on developing the product instead.

Seaweed Solutions has nevertheless benefited greatly from the market-related activities required by their EU support. They have had collaborative projects with research groups in France, which were instructive. They are also collaborating with the Norwegian University of Life Sciences on the use of kelp in animal and fish feed.

“Now we’re looking ahead, and it’s fun to see the growing interest in kelp as a sustainable food,” he says.

Nevertheless, their production isn’t profitable yet. They operate at a relatively small scale and still have a lot of research and development work to do.

High iodine content

Sugar kelp has a particularly beneficial effect as a flavour enhancer, and can replace salt.

“By adding a half per cent of sugar kelp to products, food producers can significantly reduce the salt content,” says Dagbjørn Skipnes from Nofima. There are lots of advantages to lowering the salt content of foods, especially for people with high blood pressure.

Some kelp varieties contain very high amounts of iodine. That may sound nice, because half of Norway's population consumes too little iodine. Pregnant women especially need to be aware of getting enough iodine.

But as with anything else, moderation is important. And the iodine levels in kelp have to be seen in the context of the other iodine-containing foods a person might consume.

Iodine is found mostly in milk, dairy products and saltwater fish.

“If you otherwise get enough iodine, your iodine intake could be too high if you also eat sugar kelp several times a week,” says Skipnes.

But for vegans, kelp could be a good source of iodine, he said.

50 grams covers the daily requirement

For most people, the iodine level in sugar kelp can be too high, if you eat a lot of it. Raw, dried kelp in particular contains a lot of iodine.

If you stay under 50 grams of boiled sugar kelp, you probably won’t get too much iodine, postdoctoral fellow Marthe Jordbrekk Blikra in Nofima said to sciencenorway.no.

When you boil or soak kelp, iodine leaches into the water.

Nofima is now studying processing techniques that would make kelp suitable as human food.

“Boiling is most effective in reducing the iodine content of sugar kelp. Blanching also works, when temperatures are about 45 degrees,” Skipnes said.

Brown algae, of which sugar kelp is a subspecies, also changes colour from brown to fresh green. Drying kelp does not significantly change the iodine content.

Winged kelp has a significantly lower iodine content.

Skipnes points out that the Norwegian Food Safety Authority recommends a daily intake of iodine of a maximum of 600 micrograms on average for adults.

“It’s important that manufacturers label packages with the recommended daily intake, and the best cooking method if it is sold directly to consumers,” says Blikra.

Exciting job potential

In China, Japan, Korea and Vietnam, kelp farming is a major industry. There’s not much kelp farming in Europe, but some people do harvest kelp that grows naturally.

As much as 60 per cent by volume of the kelp from Europe is harvested by trawlers along the Norwegian coast.

“Kelp is only sold in shops in Denmark or Iceland, and is used more often in dishes at restaurants in these countries,” Skipnes said.

He believes kelp farming is really good for the climate and the environment. Not only because it does not need to be fertilized, but because it only needs fresh seawater and sunlight. And also because it takes up CO2 and produces oxygen.

“It’s a very sustainable industry. It’s exciting that this industry can provide nutritious food, and at the same time create new jobs in Norway,” he said.

Translated by: Nancy Bazilchuk

References:

M. J. Blikra, D. Skipnes et al.: "Utfordringer knyttet til prosessering og analyse av norsk tare, med fokus på sukkertare og butare,” (Challenges related to processing and analysis of Norwegian kelp, with a focus on sugar kelp and winged kelp) Report 34/2020, Nofima (in Norwegian).

———