Peacekeeping from cyberspace

YouTube videos, data about the location of mobile phones and volunteers who translate and make maps via digital networking are some of the new tools that are bolstering peacekeeping forces, according to a Norwegian researcher.

Denne artikkelen er over ti år gammel og kan inneholde utdatert informasjon.

If refugees increase the amount of money they send back to their home country, it might be a sign that the situation there is becoming more precarious. If a large number of mobile phones are all moving in the same direction, something may be about to happen.

John Karlsrud, a researcher at the Norwegian Institute of Foreign Affairs (NUPI) says if people whose job it is to keep the peace in these areas can access this kind of data, they have a better chance of saving lives.

It’s a long road from Gaza in 1956 to Afghanistan today. In the Cold War days, peacekeeping operations consisted of little more than multinational military forces deployed to monitor peace agreements.

Now the duties of multinational forces range from the traditional protection of civilians and attempts to keep the peace, with force if necessary, to efforts at starting up new states with all the institutional trimmings a society needs, both during and after a conflict.

But NUPI’s John Karlsrud says that today’s peacekeepers are not fully equipped to make use of our current digital reality. Karlsrud has written a chapter addressing these ideas in the recent book Cyber Space and International Relations (Springer, Berlin 2013).

The chapter, entitled “Peacekeeping 4.0, Harnessing the Potential of Big Data, Social Media and Cybertechnology”, looks at how using 21st century digital tools can hasten and improve efforts to save lives.

Karlsrud has personal experience with peacekeeping and development assistance. He spent two years as a special assistant to the UN’s special envoy to the Republic of Chad and has worked with the UNDP. He is currently working on a PhD on the UN’s peacekeeping operations.

The researcher points out that peacekeepers are making progress, and new tools and opportunities are plentiful. The UN has its first drones in the air, at least the first that have come to the attention of the public. These are equipped with cameras and sensors, and are being used over the Democratic Republic of Congo.

“Surveillance drones provide more information, but they also add to pressure on the UN to ensure adherence to the Geneva Convention and the principle of protecting civilians. The UN is often accused of not protecting civilians enough. Some of the reasons the organisation doesn't do as much as it might are fear of ambushes and lack of information,” he says.

“Now they can get to the scene with drones and check things out first,” explains Karlsrud.

Although the use of the first drones has not been fully evaluated, the UN wants to spread their use to South Sudan and the Ivory Coast.

Volunteer mappers

Better equipment is just one tool available to peacekeepers. Experiences from the election violence in Kenya and the earthquake in Haiti can be transferred to military peace operations.

“The website Ushahidi, which means ‘proof’ in Swahili, was set up after the ethnic violence linked to the elections in Kenya in 2008. Anyone with access to digital communication can report violent episodes and the website used the reports during the Kenyan crisis to chart the outbreaks,” says Karlsrud.

During the Haitian earthquake of 2010 text messages flooded in from people trapped in collapsed buildings.

“The messages were often in Haitian Creole. Volunteers from the Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy at Tufts University in Massachusetts pinpointed the messages on a map and got them translated with the assistance of 1,200 Haitians living in the USA,” he said.

Even the map had to be made from scratch. Scores of volunteers helped draw up a detailed map, combining roadmaps and observations. Karlsrud said this made the map of Port-au-Prince one of the best and most detailed found anywhere.

Danger of misuse

The threat to lives from from a conflict, rather than a natural disaster, raises an entirely different range of issues. Karlsrud cites Syria as an example. Syria Tracker is based on not only text, photos and videos that are uploaded to the website, but also uses updates from the likes of YouTube, Facebook and Twitter.

The risk here is that as live updates about attacks or violent episodes are placed on the map and made public, hostile parties or looters can use the information to their own advantage.

The same risk arises as increasing amounts of data come in formats that can be interlinked.

“People are more vulnerable when this gets into the wrong hands and is used contrary to the intended purposes. So the players who are collecting data increasingly need to evaluate their vulnerability and whether they are protecting their data adequately, ” says Karlsrud, who adds that the UN system leaks like a sieve.

Money and phones

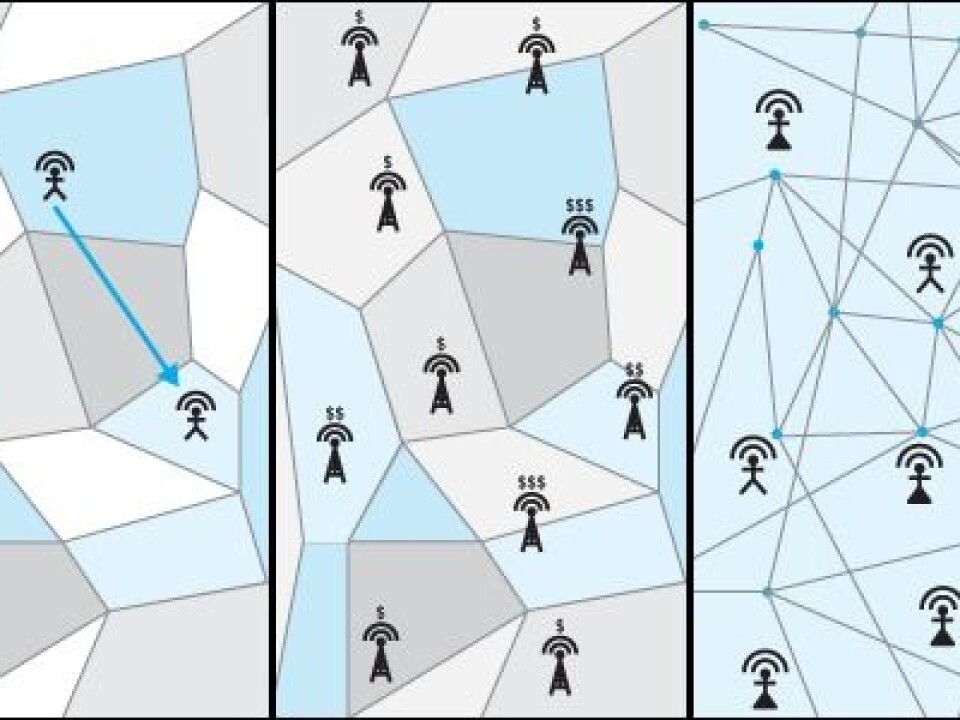

The overviews that are controlled by banks and telecoms, for example, can also provide vital information to help peacekeepers respond quickly. But it’s not a given that the companies are willing to divulge such data. The NUPI researcher says that if they are willing, there is a world of difference between data on identifiable individuals and data on large trends.

“When expats start sending more money to their families in their home countries it can be a sign of mounting vulnerability there. It may means there are crop failures or other things which should make us heighten our awareness. We see the same thing when a population is using less and less money on refilling their phone cards. When they fill them up with two dollars instead of ten dollars, that means there are money shortages,” explains Karlsrud.

“Google already cooperates with the UN. Facebook and Twitter can do the same. If there is a spike in hate words and terms of derision on the Web, it might suggest that a conflict is brewing,” he said.

Referance:

John Karlsrud, Peacekeeping 4.0: Harnessing the Potential of Big Data, Social Media, and Cyber-technology, in Kremer, J. F. & Müller, B. (red.), Cyber Space and International Relations. Theory, Prospects and Challenges, Berlin, Springer (2013).

-----------------------------

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no

Translated by: Glenn Ostling