What would a Norwegian version of Bridgerton look like?

Norway stands out in Europe as a country where the nobility was almost insignificant, and in 1814 noble titles were forbidden. Still, in some circles in the capital, women dressed like their British trendsetter counterparts.

In the Netflix costume drama Bridgerton, the British elite spend their time frivolously moving from one social event to another in a succession of stunning London manors and estates.

What were the Norwegians doing at the time? Were big society balls, maliciously weaponized rumors and carefully arranged marriages the order of the day in early 19th century Norway as well?

The Norwegian elite was significantly smaller, according to historian Jan Eivind Myhre.

But the country still had people who were classier, richer and more noble than the rest of the population.

The nobility in Norway

The English nobility consisted of dukes and duchesses, counts and countesses, barons and baronesses, and they all played a role in the social life of 1813.

In Norway the nobility was almost insignificant, according to Myhre, a retired historian at the University of Oslo.

“Norway stands out from almost all other European countries in this regard,” he says.

Norwegians had their officials, who were officers, priests and judges.

In addition, merchants and businessmen who had made a fortune exporting timber abroad were called the plank nobility, although most were not really of the nobility. But they were rich.

“They were part of the social life in all the big cities in Norway,” Myhre says.

Because Christiania was the capital (what is today called Oslo), many more families of officials and businessmen lived there than elsewhere. They circulated among themselves and married each other, according to Myhre.

One society man in particular

One of the families in Christiania responsible for social life was that of the lumber merchant John Collett.

He was one of Christiania's foremost citizens, and with his wife Tina, at the centre of the city's luxurious social life.

Collett was a landowner and had several homesteads, including Ullevål farm in Aker municipality and the legendary country house Flateby in Enebakk municipality.

Flateby was a hunting lodge where annual autumn hunts were held, and the Christmas celebrations were magnificent and spectacular – with dramatic spectacles, comedy games and masquerades.

The buildings were demolished in 1840, but traces of them remain in documents written about the place.

Scandals on the estate

Handwritten Flateby journals describe in detail how the parties went and who was there.

“It's like reading an 1800 version of Facebook, with lots of hints of scandals,” says Janne H. Arnesen. She works at Norway’s National Museum of Art, Architecture and Design in Oslo.

“Flateby would fit right into Bridgerton!” she says.

The Collett family also arranged parties at Ullevål farm. The large garden was designed as an English landscape garden, including a fish pond with rare birds, party halls with Greek temples or dilapidated church ruins, and a cave clad with mussel shells.

How were the ladies dressed?

"Ladies and men among Oslo’s elite and at Collett's parties were attired similarly to their British counterparts,” says Arnesen.

She notes that several examples show how England was a stylistic ideal for Norwegians.

Arnesen mentions Mary Wollstonecraft, an English women's rights activist who travelled to Norway in 1795. Wollstonecraft later wrote in a letter, “The first evening of my arrival I supped with some of the most fashionable people of the place; and almost imagined myself in a circle of English ladies, so much did they resemble them in manners, dress, and even in beauty.”

“Everyone who traded with England brought home a number of goods, whether it was furniture, watches, art, food, drink, textiles or fashion,” Arnesen writes.

She also points out that English style and fashion were a better fit for Norwegian conditions – especially the climate – than French style and fashion were.

“The families referred to as the plank nobility made big profits on the export of timber to England and were leaders in that way,” Arnesen writes.

Dresses in the Empire style

The National Museum's collections include a number of costumes and portraits that show urban fashions among Norwegian high society.

“Here you can see what was fashionable in the larger cities along the coast,” writes Arnesen.

Scroll through the photo gallery below for more Empire-style dresses:

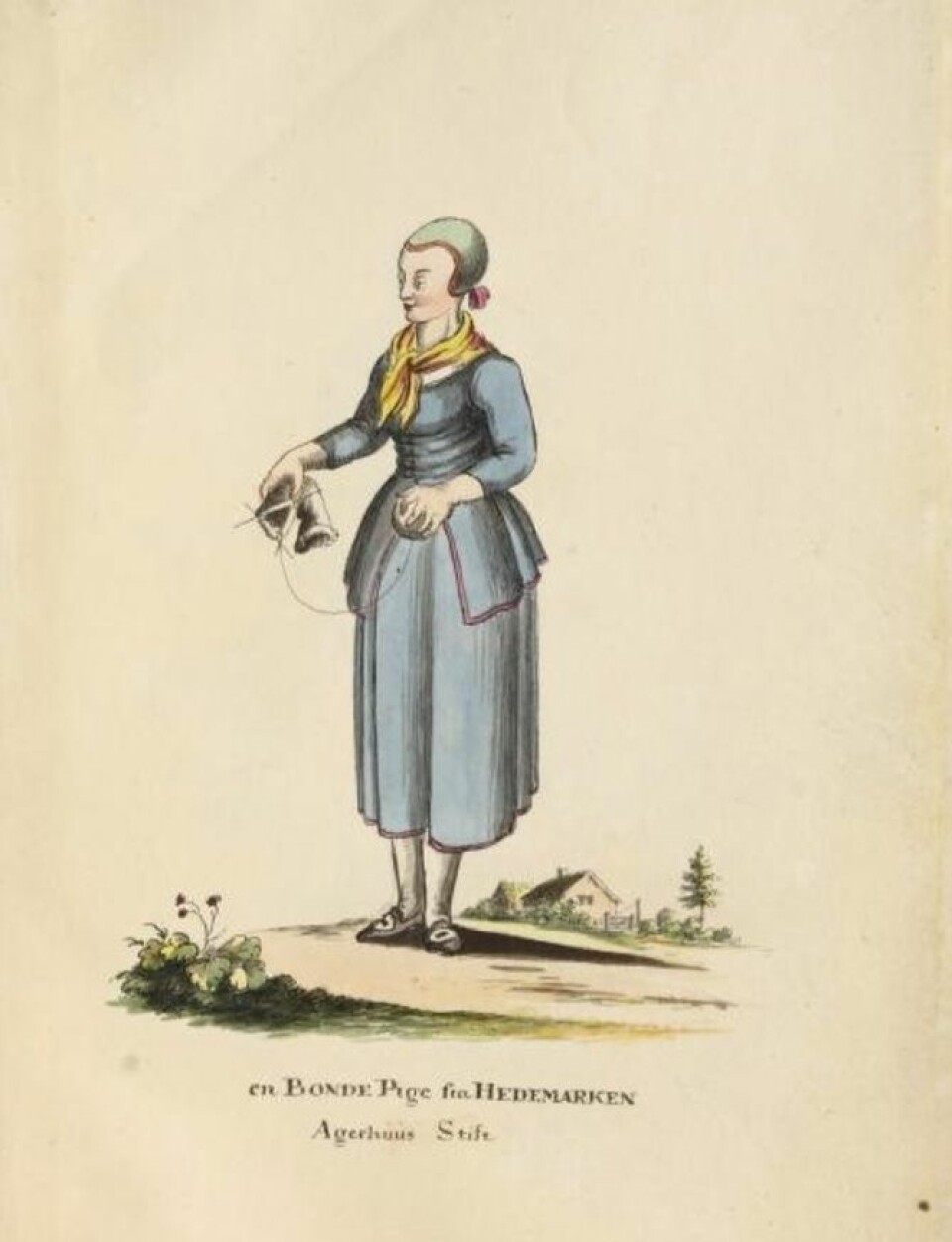

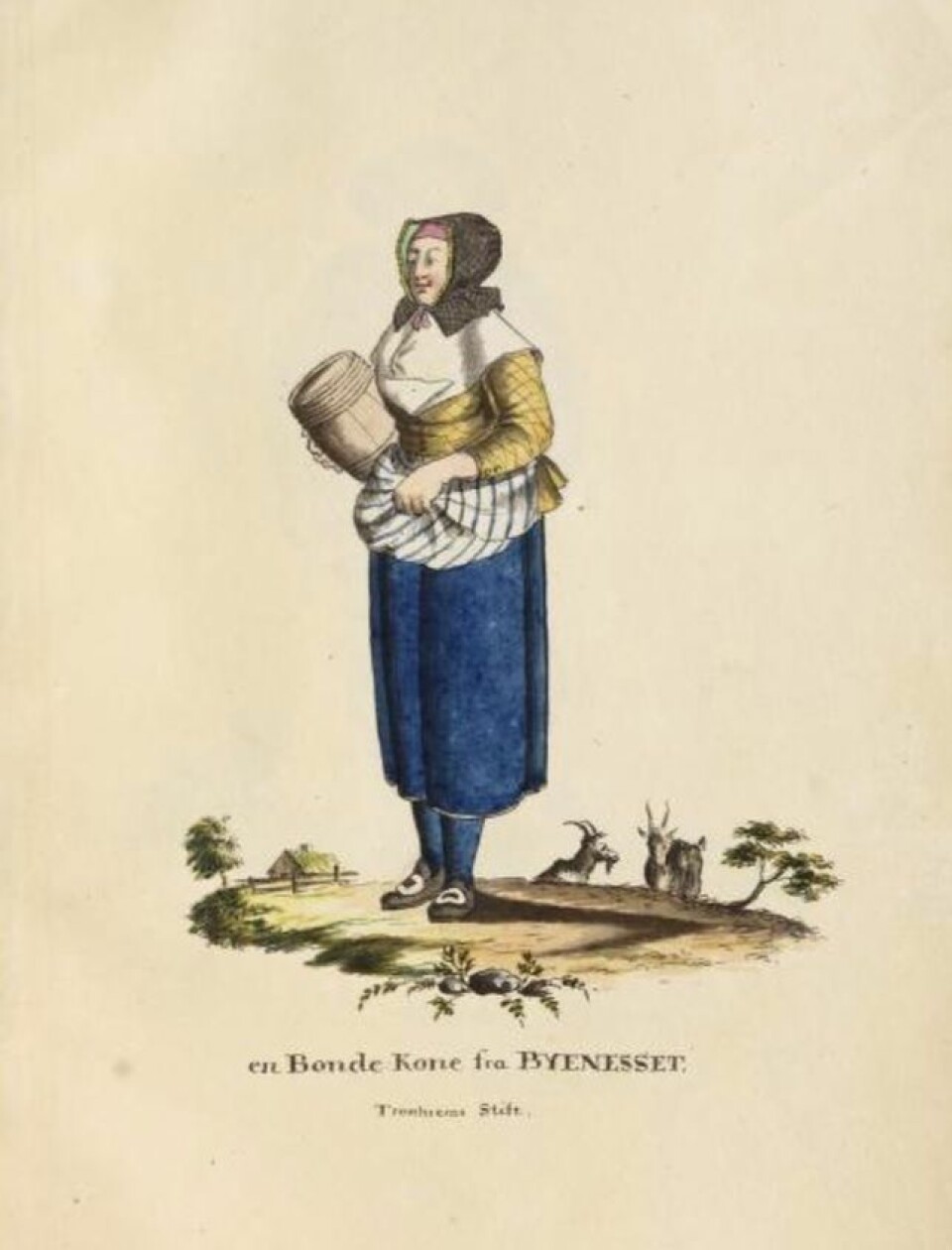

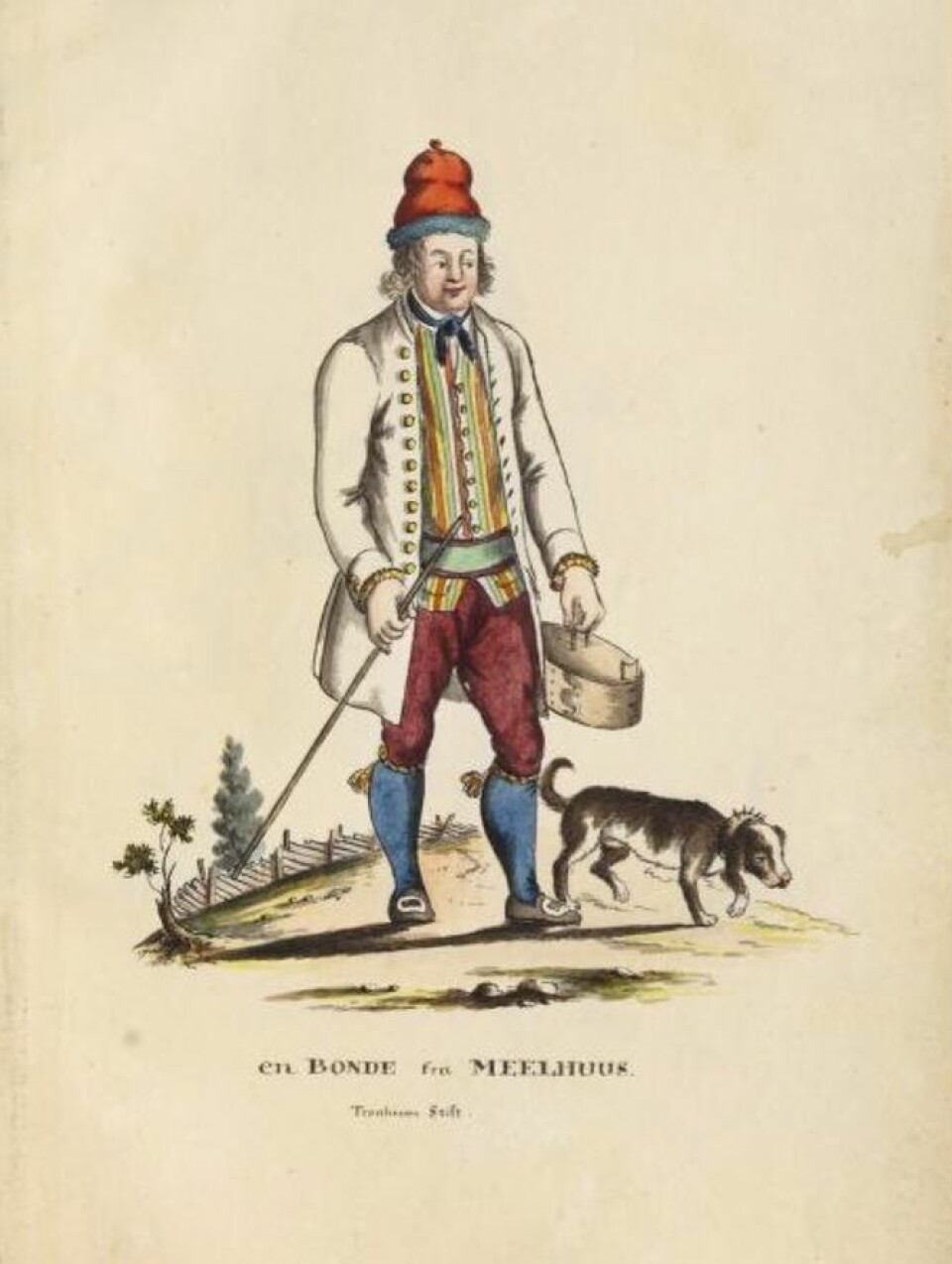

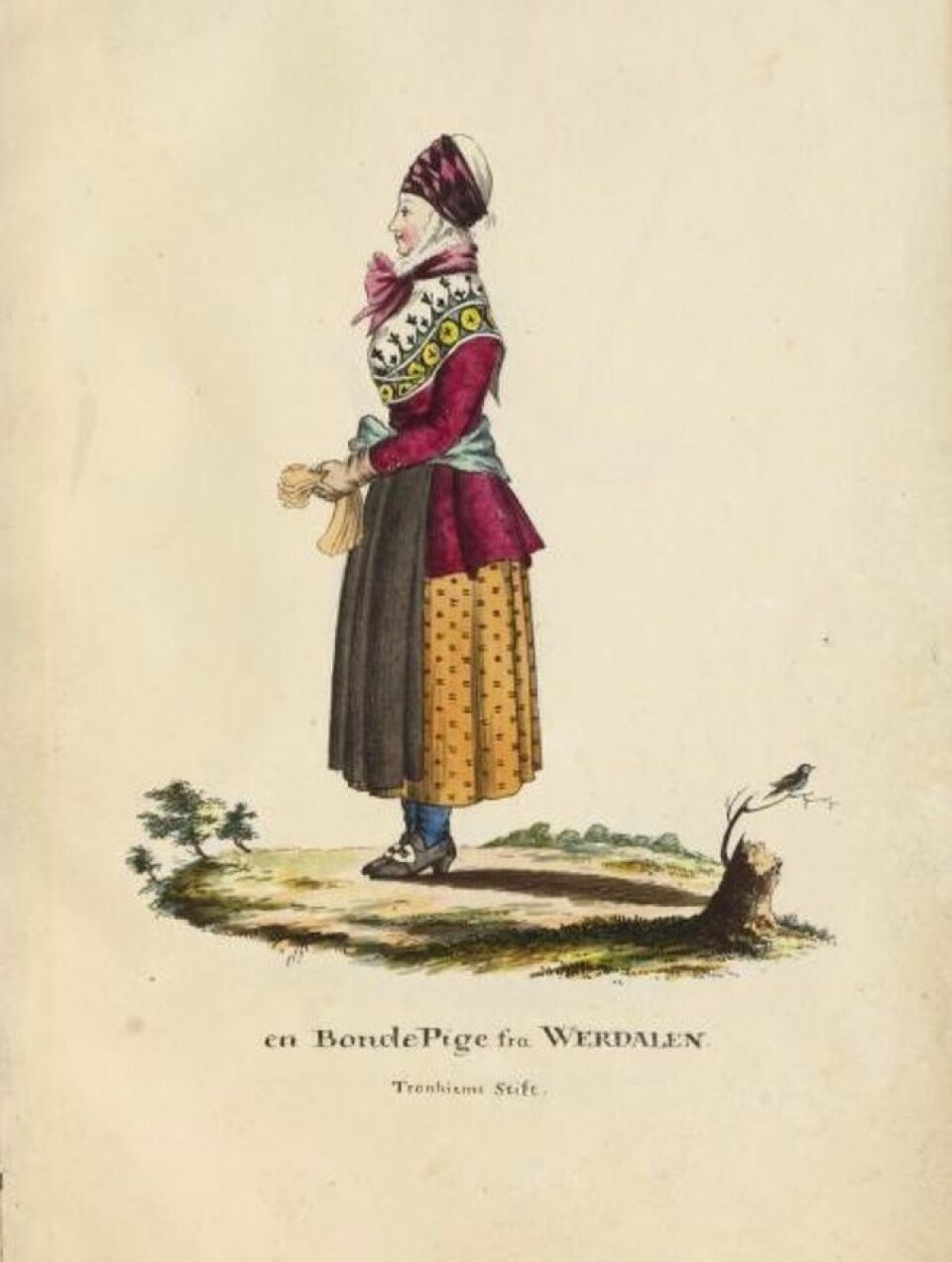

Country folk dressed differently

Women and men who lived outside the big cities of Oslo, Trondheim and Bergen, on the other hand, looked different.

At the end of the 18th century, the Danish-Norwegian king issued a so-called "Reduction of Abundance in the Peasantry" (Overdaadigheds Indskrænkning i Bondestanden).

These were a series of sumptuary laws to prevent the non-nobility from spending money beyond their means.

The laws included rules for the import and use of silk fabrics and of clothes with and without embroidery.

In 1783, a law was introduced that forbade people to use gold, silver or silk embroidery, garments with interwoven gold or silver, foreign lace and gold and silver braiding.

An adjustment came two months later:

“None of the peasantry in the country, young or old, married or unmarried, may wear clothes other than of home-made cloth, such as homespun or woven, and the like; women must never wear silk blouses or skirts, or silk scarves; however, they may wear a silk hat, and top and skirt that are purchased, and the farmers may likewise wear a purchased top or vest.”

Distinctions were important

“According to the legislation, distinctions between urban fashion and rural fashion, and between the peasantry and civil service and nobility were necessary,” Arnesen writes.

The clothing people wore was not only based on their preferences and what they could afford, but also what they were allowed to wear by law.

“That said, we don’t know how strictly people complied with the legislation in different parts of the country,” says Arnesen.

Scroll through the photo gallery below for more folk costumes:

Constitution put an end to clothing bans

The strict laws on how people were allowed to dress dissolved throughout the course of the 19th century.

The Dano-Norwegian absolute monarchy ended in 1814, when the Norwegian constitution was drafted.

“The king no longer dictated Norwegians' clothing choices. In addition, cotton came into vogue throughout Europe, and large factories were able to produce more and larger fabrics than before, supplanting the demand for exclusive hand-woven silk. The times and needs changed,” writes Arnesen.

Noble titles forbidden in Norway

Prior to 1814, the few nobles in Norway were part of the Danish-Norwegian nobility, says the historian Myhre.

They had names preceded by "de" or "von," such as de Vibe and von Krogh. There were also people with names like Rosenheim, von Munthe af Morgenstierne, Tordenskiold, Lilienskiold, Werenskiold and Løvenskiold.

But the new constitution actually abolished the nobility in Norway. King Karl Johan was reluctant to approve this move, but found himself forced to adopt the ban from the Storting in 1821.

Now the constitution states that there shall be no nobility in Norway:

The Constitution of 1814 (§ 23) provided that no personal, or mixed, hereditary privileges "must be granted to anyone for posterity" and forbade (§ 108) the establishment of new countships, baronies, noble houses and fidei commissa.

Nobles born before 1821, on the other hand, were still allowed to carry their titles like count and baron. They just didn’t mean anything anymore.

“The most famous noble family in Norway was Wedel Jarlsberg and included Count Wedel Jarlsberg and his brother the Baron. They kept their name, but they were no longer nobility after 1821,” says Myhre.

Translated by: Ingrid P. Nuse

Sources:

Johan Friedrich Dreier: Norske Folkedragter. (Norwegian Folk Costumes.) 1890. The National Library of Norway.

Empire style and classicism. Collection at the National Museum.

Ragnhild Bleken Rusten: Folkedrakt og bymote i Gudbrandsdalen 1650-1940. (Folk costumes and urban fashion in Gudbrandsdalen 1650-1940.) Thorsrud, Lokalhistorisk forlag. 2002. ISBN9788278470824

Mary Wollstonecraft: Letters Written During a Short Residence in Sweden, Norway, and Denmark (1796), digitized at the National Library here.

———

Read the Norwegian version of this article on forskning.no