Share your science:

Menstrual art: Why do people still see red?

SHARE YOUR SCIENCE: Period blood in art is still often dismissed as a joke or “just activism”. Would that be the case if it wasn’t such a taboo?

In some century, somewhere in the world: A person is bleeding, visibly staining their clothes. A well-meaning friend whispers ‘hey, I think the painters are in’. The person wears a sweater around their waist for the rest of the day.

While ‘having the painters in’ is associated with a mortifying experience for many, my recent research project takes the saying literally. It may not be socially acceptable to bleed in public, but artists seldom care about conventions. While most people wrapped a sweater around their waist, artists did the opposite.

Menstruation as a creative opportunity

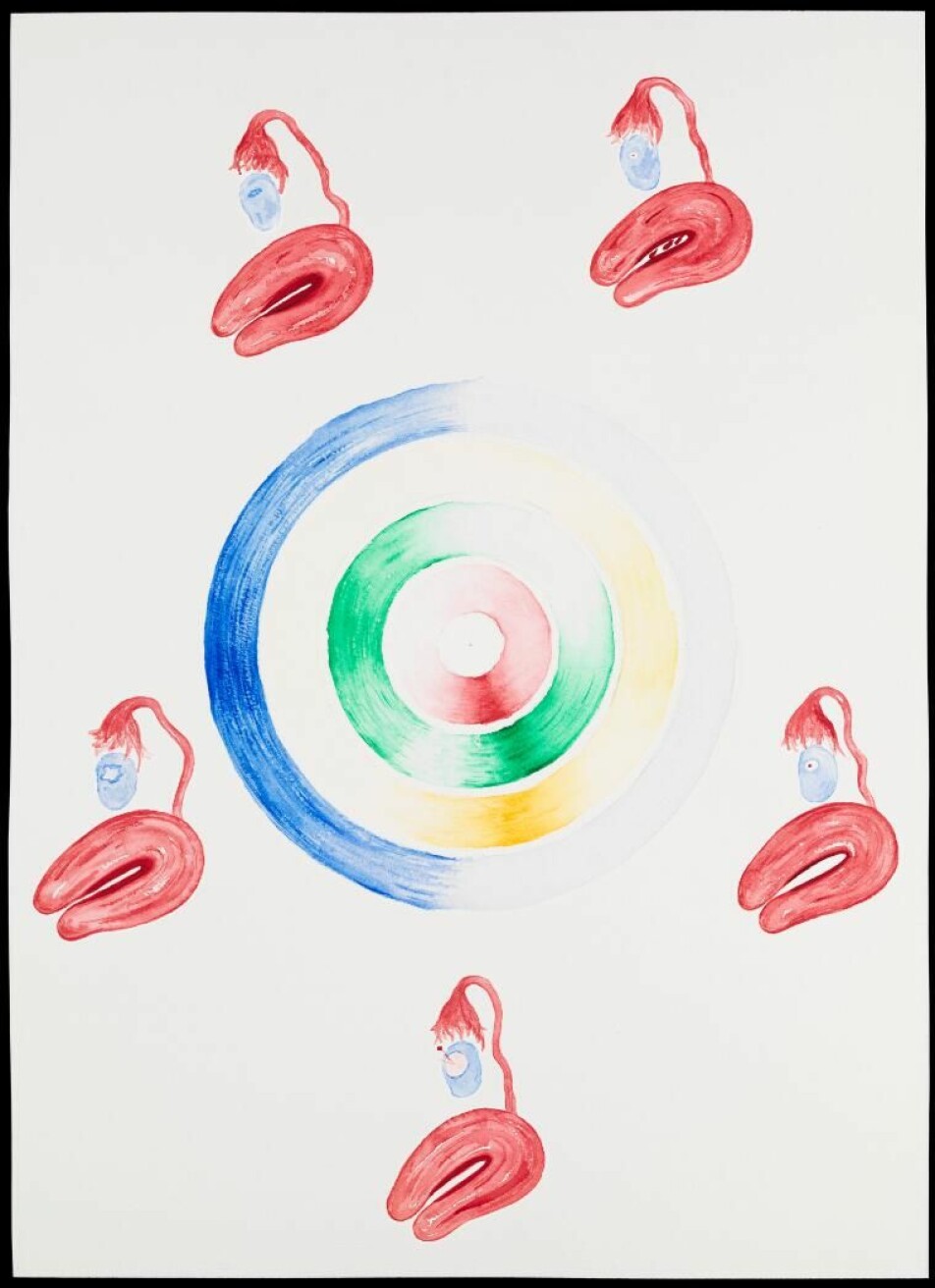

In the eyes of artists, menstruation has been conceptualised as a fascinating subject of creative interpretation, exactly because other areas of society have largely dismissed it. Drawn to topics others shun, many artists have gravitated towards menstrual themes over the last seventy years, finding it fascinating and exciting. In this parallel history of menstruation, ‘having the painters in’ is a creative opportunity to invent a new visual language for a bodily event weighted down by a medicalized and gendered history.

These artists elevate menstruation into the realm of art, but have faced many challenges in doing so. In this way, menstrual art serves as a poignant example of how menstrual taboos work, and how those who seek to explore the topic frankly can still be shamed. Menstrual art is (still) often dismissed as a joke, a stereotype of Second Wave feminist art, and as ‘just activism’ – an example of how the menstrual taboo disciplines those who step out of line.

But is it art?

For instance, in 1971 artist Judy Chicago removed a used tampon from her vagina, immortalised the action as the photolithography Red Flag, and framed the resulting image as an artwork. Fifty years later, artist Rupi Kaur also created a menstrual self-portrait in photographic form. Period showed the artist lying on her side with a small bloodstain visible on her trousers. The image was widely disseminated as part of thematically linked series of photographs on the platform Instagram. Despite the decades separating the creation of these artworks, Chicago and Kaur have much in common. In her autobiography, Chicago documented that the work was found controversial and that she struggled to exhibit it. Kaur’s work was likewise censored on social media, resulting in anger from the artist and an apology from Instagram.

Whether made in the 1970s or 2010s, menstrual art seems to attract the same questions. Is this suitable for public consumption and dissemination? What exactly is being shown and why? Is this even art? Or ‘just’ activism? Who should make it, and who should not? In my research, I attempt to draw links between various forms of menstrual art, to investigate whether or not public assumptions about menstruation and its visual representation are in fact changing. By the time Kaur’s work was again allowed to be published on Instagram after a public debate, Chicago’s photolithography was finally being somewhat accepted in the art world, in major retrospectives of the artist.

Yes, menstruation is having a moment, but this arguably makes its history even more important. Scholar Chris Bobel found that activists, academics and media tend to overlook the history of the movement, focusing instead on present-day concerns. Such approaches tend to stress the importance of technological progress and access to products designed to hide menstrual blood altogether. In contrast, artists occupy a somewhat different space in this history, as people who approach menstrual blood with curiosity and enthusiasm.

Patriarchy, racism, capitalism...

The ways in which artists have approached the topic of menstruation has varied greatly, although most artists focus on the bleeding stage of the cycle rather than, for example, ovulation, cramps, or the pre-menstrual week. Menstrual blood is almost always involved, but the ways in which this is depicted varies. Referencing the current medical and public debate about what a ‘normal period’ looks like (what constitutes heavy bleeding? What colours should be expected? What frequency?), artists have shown diversity in blood texture, colour, and quantity for decades. This reminds us that menstruation is not a streamlined 28-day cycle affair. To the contrary, menstrual art shows not only the diversity of representation, but the diversity of associations with menstruation. Artists link this bodily event to patriarchy, racism, capitalism, medicine, disability, beauty, and formalist approaches to art.

Furthermore, they present these ideas in photography, oil painting, performance, sculpture, digital art, in textile, and much more. Overall, the diversity of representation, ideas, methods, and form in menstrual art as a whole demonstrates the complexity, as opposed to singularity, of menstrual experiences.

For viewers of such works, there also seems to be a corresponding variety of opinions, perhaps reflecting their own experiences – or lack thereof – of menstruation. For instance, depending on whether or not you have a cycle, and if this is a cycle of intense debilitating pain, your view of these works may be radically different to others. Likewise, for some of the artists surveyed in my research, menstruation is a monthly nightmare associated with pain and body dysmorphia, whereas for others it is a beautiful or neutral event. As such, menstrual art provides a service unique to the realm of the arts –inviting us to think about the iconography that has been dismissed or accepted as ‘normal’.

Not beneficial for the artists to be linked to menstrual themes

Despite the ways in which menstrual art disrupt myths, it should also be noted that almost none of the artists surveyed for this project consider themselves ‘menstrual artists’, but rather incorporate menstruation in their overall practice. Like other aspects of menstrual taboos, it is not lucrative or beneficial for artists to associate themselves closely with menstrual themes over a long period of time. This concern is linked to a wider issue facing artists who work on any theme connected to social justice – the danger of being perceived as a ‘mere activist’.

Although recent shifts in the commercial art world has seen a move towards more diversity and a general openness to transgressive themes, change is slow. For now, menstrual art remains on the margins of the art world. This is not entirely negative, because the field is not restricted by a canon, hierarchies, institutional structures, prizes, auctions, nor fame. Rather, menstrual art is created by an ever-revolving cast of different people from around the world, who momentarily become enthralled with menstruation, create art in response to it, and then move on. Amateurs and big names exist side-by-side, making this topic of art both a challenge and exciting opportunity to explore within the confines of art historical movements.

What would the world look like, if menstrual blood was not a taboo?

Menstrual art provides a valuable and rare look at an alternative world in which periods were never taboo. Most menstruators do not consider bleeding freely. It is neither practical, nor socially acceptable.

The few public debates about this underscore the overwhelming persistence of the taboo against menstrual blood. Artists, as human beings, of course also face this dilemma, but chose to ignore it momentarily. Through often painstaking methodological and material labour, they document their body and present it to viewers. For years, they live with the knowledge that people have seen their stains, that the ‘secret’ is out there. As such, they have transgressed the ‘passing’ process of appearing non-menstruating at all times – they have refused to fall in line and cover up their bloodstains like the rest of us.

The radical idea of menstrual art is the artist’s generous offering of their own body, and their subsequent invitation to imagine ourselves in their place. What would the world look like, if menstrual blood was not a taboo? What would be the consequences of simply bleeding? If we still felt squeamish, would that also be OK?

Making mensturation visible

The 2010s saw the rise of public debates about Period Poverty, the Tampon Tax, endometriosis, menstrual shame, and resistance against environmentally damaging menstrual products.

Artist provide us with a different view, which largely sidesteps debates about implementing policy and providing free products. Rather, artists have kept focused on the issues regarding menstruation that cannot be solved by a ‘technology-fix’, and have also showed the ways in which the menstrual cycle may be considered a positive event.

Fresh blood has been served up both literally and metaphorically, as these artists momentarily disrupted a visual paradigm heavily invested in secrecy. While ‘having the painters in’ remains a private affair for most menstruators, the painters themselves have long turned the euphemism on its head by dismissing the ‘menstrual concealment imperative’ and making menstruation visible.

Share your science or have an opinion in the Researchers' zone

The ScienceNorway Researchers' zone consists of opinions, blogs and popular science pieces written by researchers and scientists from or based in Norway.

Want to contribute? Send us an email!