The art of making a living: How to survive as an artist

Not giving up is more important than being the best. That was the advice Marius Johnsen received as a young art student. A new book deals with artistic life in Norway today.

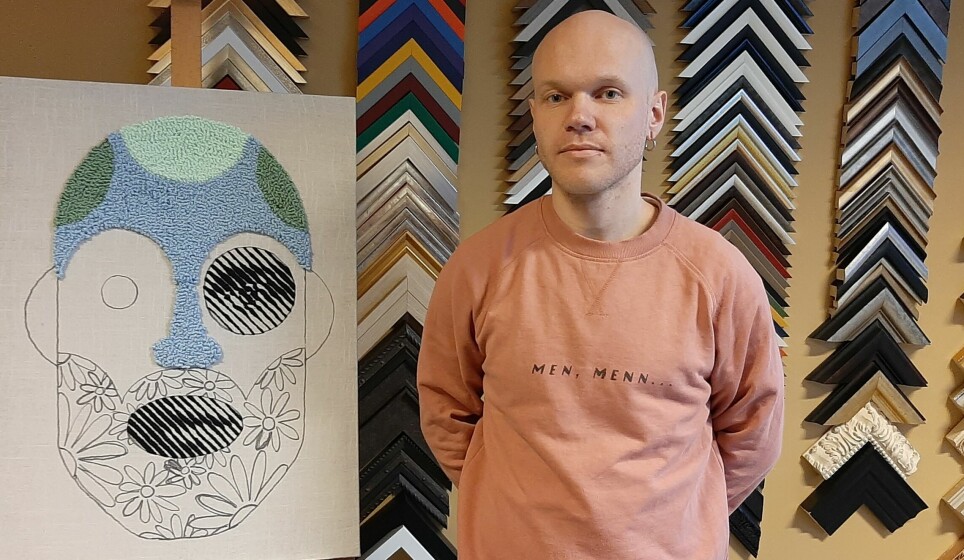

Marius Charles Johnsen is 33 years old. He graduated as a visual artist seven years ago.

It’s been a lean year.

We meet Johnsen at the frame shop he runs in Oslo’s Linderud neighbourhood.

He wanted to become an artist from a young age.

“Once, as a teenager, I was at an exhibition. I didn't understand the language artists used or the works I was looking at, but the experience made an impact. I wanted to understand more," he says.

Johnsen started painting when he was 15, and he sold his first painting right away. For a few years he considered various educational directions. He finally settled on an art programme at a Norwegian folk high school.

“The urge to create became all-consuming. I decided to become an artist,” he says.

The chosen few

At the age of 23, Johnsen was among a select few who were accepted to study at the Oslo National Academy of the Arts. He was one of eight students in the art and craft department.

20 years ago, researcher Per Mangset conducted a study of 30 young and ambitious art students.

They were studying to become actors, musicians and visual artists. They were among the lucky ones who had obtained coveted places at Norway's best educational arts institutions, including the National Academy of the Arts.

The students aspired to conquer the world with their pictures, sculptures and installations.

How did they do? Are they artists today? Are they able to make a living from their art?

Knew it would be tight

Professor emeritus Per Mangset and two colleagues from the Telemark Research Institute set out to investigate these questions. They recently published the book Fortellinger om kunstnerliv (Stories about artists’ lives).

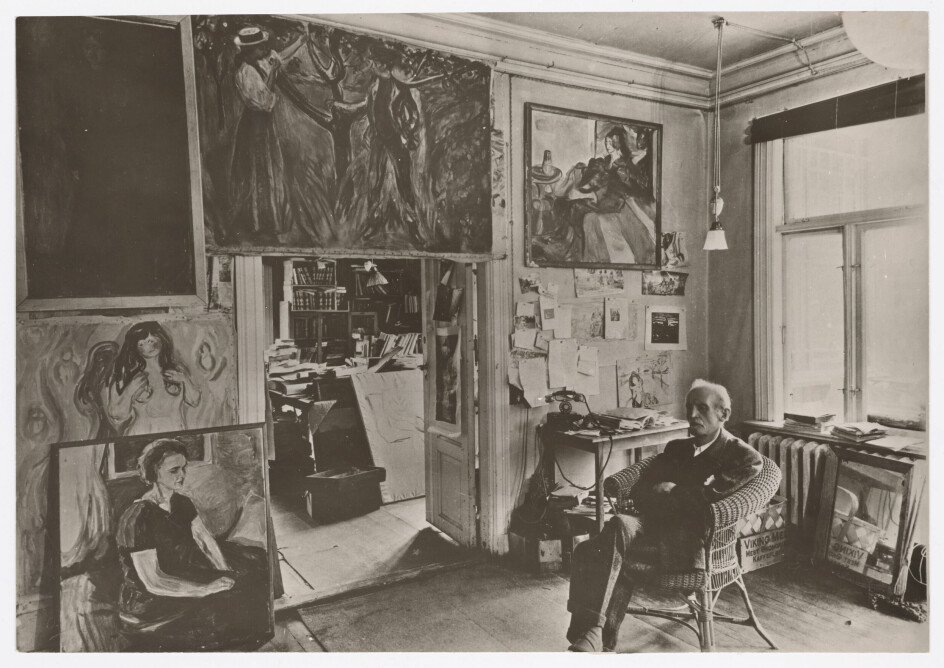

Many of the most famous painters were poor during their lifetime.

Edvard Munch was well into adulthood when he had his breakthrough. Before that, everyone thought his pictures were "filth that they didn't want on their walls," he wrote in a note. The Dutch artist Vincent van Gogh first received recognition 30 years after his death, according to the Great Norwegian Encyclopedia.

The seven visual artists at the Oslo National University of the Arts were aware that making a living from their art could be tight. When they were interviewed for the first time in 1999, they knew they were facing an uncertain labour market.

Artists depend on someone liking what they create and being willing to pay for it.

Nevertheless, they dreamt of a life where they could make a living as artists.

Marius Johnsen also knew that it was going to be tough.

Caravan in a village in Eastern Norway

“We were told at the Academy of the Arts that only a small per cent of us would succeed as artists. The rest would give up,” says Johnsen.

He received a piece of advice from an older artist: " Not giving up is more important than being the best."

Johnsen has followed that advice.

But it hasn’t been an easy life.

“There have been periods when I haven’t been able to make art, because I had to have an income. It's all about finding time to make pictures. I’ve sacrificed a lot,” he says.

A regular home is one of the things he has given up. He now lives in a caravan in Ytre Enebakk, a village in Eastern Norway. The winters are cold.

“I need a sleeping bag under the duvet at night,” he says.

The myth of the born artist

When Mangset spoke to the budding artists for the first time, the myth of artistic genius was firmly entrenched.

The myth goes that some people are born artists. They have great talent just waiting to be discovered.

Several of the art students spoke in this way in 1999. They saw only one path for themselves, and that was straight into art.

“It's something I have to do, in a way I have no choice. If I had a choice, I would have chosen something else," Kari says in the book.

“The myth of the born artist is not as strong today,” Mangset says.

After 20 years, all the students he interviewed have found a reasonable way to live their lives, but often not from art alone.

Accepted the risk

As brand new graduates, they had great faith that they would succeed.

“In the initial phase as artists, they lived with high risk. They combined artistic work with other jobs. But they were enormously motivated and were prepared to live with the risk,” says Mangset.

Even though artists know that a lot of people fail, they often have a blind faith that they will succeed.

“It’s called a misunderstood probability calculation – when someone underestimates the risk that they themselves could become one of the many who give up,” he says.

When Mangset met them again 20 years later, only two of the artists still earned their primary income from visual art. These two do well in the market, one with visual art and the other with public art.

Easier for musicians and actors

The other visual artists have found other primary sources of income. One became a writer, another a filmmaker. A third became a teacher at the National Academy of the Arts.

They have managed to continue with art alongside more lucrative work. Only one of the art students left the profession. She became a designer for an IT company.

“When we met them again, many of them had established families with children and their own homes. They still wanted to do art, but they had reconciled their strong motivation with other needs and interests,” says Mangset.

He also interviewed musicians and actors two times. Their income-generating opportunities are easier because there are more jobs and freelance assignments available.

These possibilities do not exist to the same extent for visual artists.

Lowest income of all

Visual artists are the group with the lowest income. A few of them are doing very well, selling their works at a good price. The vast majority have to make do with average recognition and a low income.

Surveys of artist income are regularly carried out. The last survey done in 2013 showed that visual artists earned around 28,000 USD a year. Only a third of their income came from artistic work. In the same year, the average income in Norway was close to 49,000 USD, according to Statistics Norway (SSB).

The income from art also varies greatly from year to year. A visual artist can work a long time on an exhibition without knowing for sure whether any works will be sold. Some years they earn nothing.

Often they end up working in the cultural sector or in a shop or a care home.

“Artists deal with a lot of stuff. They cobble together their income from multiple sources,” says Mangset.

So does Marius Johnsen.

Sales and PR

Artists can sell their art from their own studio. They then have to be both a seller and a marketer. That takes time. Or they can sell through galleries. They would then have to find a gallery that wants to show their work.

For a period last year, Marius Johnsen was without a gallery. That was tough. Eventually he got into the Fineart Oslo gallery.

“Being represented in a gallery makes everything easier. I deliver to them, and then they do the rest,” says Johnsen.

There are several ways to make money from art, but it steals time. Artists can apply for grants, but Johnsen has stopped applying.

“You have to sell yourself as an artist. The product you sell is yourself. If I get rejected, it's hard. It feels like the product ‘me’ is bad,” he says.

When there are no buyers

Exhibitions are not guaranteed income.

“I worked on pictures for an exhibition for over a year. Then no one bought anything. The next exhibition went well. You just never know,” says Johnsen.

He made a living from commissioned works for a while. That is risky, too. Because what if the customer doesn't like the result? Then you have to start over.

“I’m no doubt living far below the poverty line in Norway. For several years I haven’t had any income from art, but only from side jobs,” he says.

Today he runs the frame shop Markant Ramme. It ensures that he makes just enough income so he can continue creating his textile art.

Networking

Several of the artists in the book talk about contacts and networks. Having contacts in the cultural elite was important, especially at the beginning of the artists' careers.

“They’re dependent on the cultural milieu in Oslo. For visual artists, this includes other artists, journalists, gallerists and Arts and Culture Norway,” says Mangset.

It is also important to be involved in professional organisations.

“A 55-year-old female visual artist who lives outside Oslo, who has focused on art only in adulthood and who isn’t connected to key art communities, doesn’t have it easy,” says Mangset.

And yet, despite the fact that artistic life is risky and financially difficult, the number of artists has increased sharply in Norway in recent decades, according to the researcher.

Will hang in there

“There’s a large influx of new artists. Everyone hopes to do well and establish themselves within an artistic profession. But a good number don’t succeed. Eventually they end up in other professions, and some have to resort to the Norwegian public welfare agency NAV to make ends meet,” he says.

Several artists interviewed by Mangset have found jobs and remained in close contact with cultural life.

“It’s all about not giving up,” he says.

He believes that their new study of the artists offers an optimistic picture. After all, they belonged to the elite few who were accepted into the best educational programmes.

Marius Johnsen has this education. Even so, many of the people he studied with have given up making their living as artists. Johnsen wants to hang in there.

“I think I’ll always want to make art, but I’m open to the fact that the journey will be a roller coaster,” he says.

———

Read the Norwegian version of this article on forskning.no