3D artists find inspiration in a bone yard

Morphing long-abandoned whalebone piles into plastic and cardboard art

Denne artikkelen er over ti år gammel og kan inneholde utdatert informasjon.

The whole project almost went by the wayside with one phone call. The captain of their chartered sailboat was on the line to let the project partners know that a storm was on its way.

When the call came, Trond Kasper Mikkelsen and his collaborators, Jan Dyre Bjerknes and André Gali, were set to embark on an art project that would bring together new 3D technology and old hunting history on the far northern island of Spitsbergen in the Svalbard archipelago.

New meets old

Whale hunting took place in the bay of Ingebrigtsenbukta in Sør-Spitsbergen National Park well into the 1920s. Thousands of beluga bones remain piled on the beach. “They just left everything after the slaughter was over,” says Mikkelsen. “I thought that place was so sick, so crazy that I had to do something with it.”

He hoped to 3D scan the bone-littered landscape, and then print 3D digital models to make art from. Now the storm threatened to derail the team’s plan.

Racing the storm

Team and captain consulted and decided that they still had enough time, barely. The two helicopter drones for aerial photography and their cameras were loaded onto the boat.

“We had planned a four-day trip, with plenty of time to work on site. Now we just had to jump on board and go,” said Mikkelsen. They raced to beat the storm and arrived at two in the morning in the light of a full moon. “After only a couple hours of sleep we went to work, since we needed to return the same evening to avoid getting caught by the storm,” Mikkelsen said.

Luckily, the new 3D technology was on their side. It was lighter, cheaper, and most importantly, faster than the professional equipment that Mikkelsen had used on Svalbard earlier.

Captured bone heaps

This time Mikkelsen just used an ordinary camera. Later, a computer would piece together the standard 2D images into a 3D model using a method called photogrammetry. He took about 25 pictures from different heights as he walked around the piles of bones.

“Then I did the same thing with the drone. I flew it in a circle around a pile. Then we flew it back and forth in a zigzag pattern over a large area, taking more pictures straight down so we could scan the whole landscape,” says Mikkelsen.

The long and exhausting workday came to an end, and the team packed up all the gear. Activity ceased, and suddenly they were struck by the stillness around them.

“Then the sun peeked out from behind the clouds, and for a moment time stood still. Past and future were insignificant. The only thing that had meaning was being present right then and there,” says Mikkelsen.

More tools in the toolbox

Mikkelsen and his colleagues made it back safely from the storm. He has returned to dForm, the digital fabrications lab at the Oslo National Academy of the Arts where he teaches digital art, including 3D modelling.

According to Mikkelsen, a huge democratization of technology is currently taking place and making many things more accessible than ever before. “Artists now have another tool in their toolbox that allows them to do projects faster and more simply. For example, we can enlarge sculptures. After an artist creates a miniature version, we scan it and bring the 3D model to a firm that mills a full-size polystyrene model to see how it will look.”

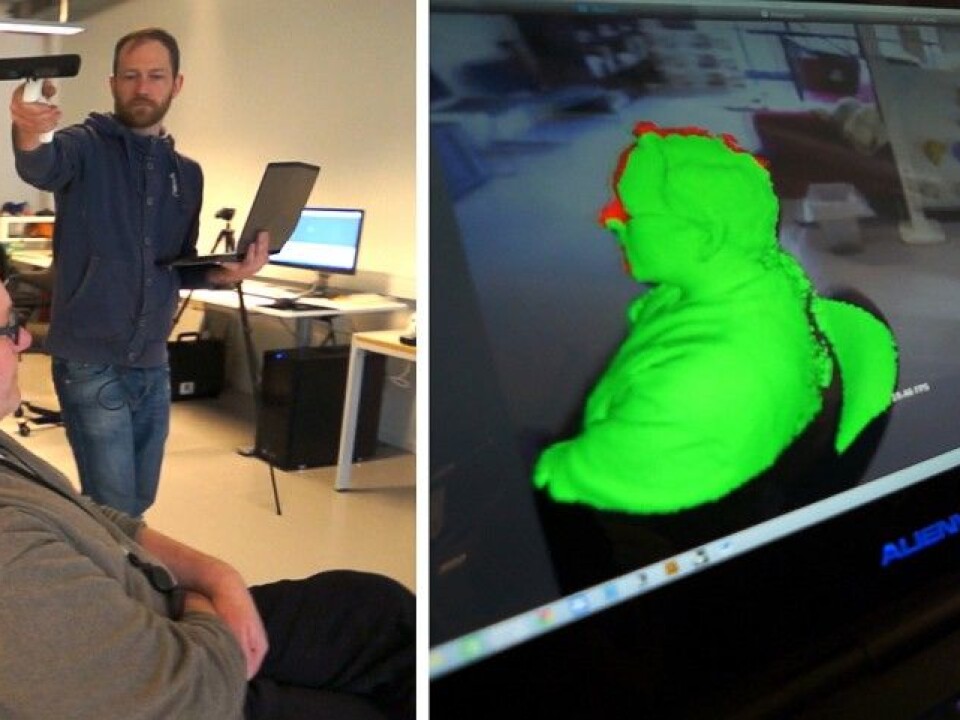

Mikkelsen demonstrates how fast 3D scanning is by calling in his colleague Tom Trøbråten. With Trøbråten seated, Mikkelsen circles him, one arm holding his laptop and his other arm waving what resembles an overgrown barcode scanner all around him. It is actually a Kinect game controller for an Xbox.

Microsoft launched Kinect a few years ago, making it possible to play computer games where you move your arms and legs and use your body to control the computer, says Mikkelsen. He explains how: “Kinect has a depth sensor that registers the distance to the moving object. That got a lot of people thinking, that if Kinect keeps track of movement and distance, then it could be used to create 3D models.”

And although the resolution is a bit low, the cost has come down from the NOK hundred thousand range for older technology to just over NOK 1000 for the Kinect sensor.

For projects that require a better result, Mikkelsen turns to the method he used in Ingebrigtsenbukta — photogrammetry. He has uploaded images of a beluga whale skull, seen from many different angles. The computer program figures out what angle they’re taken from, adjusts the perspective, and a cloud of pixels forms a 3D model.

From model to art

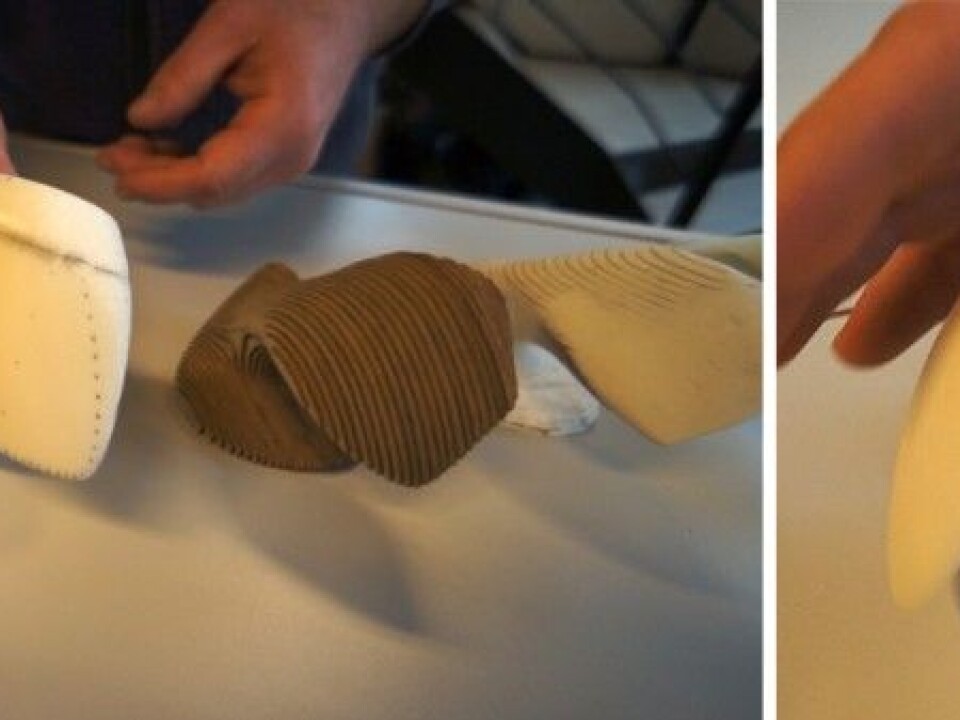

So what can an artist do with a model like this? One of the answers is found in the 3D printer room. One printer makes plastic models that are very precise and also the most expensive. It lends itself best to small models.

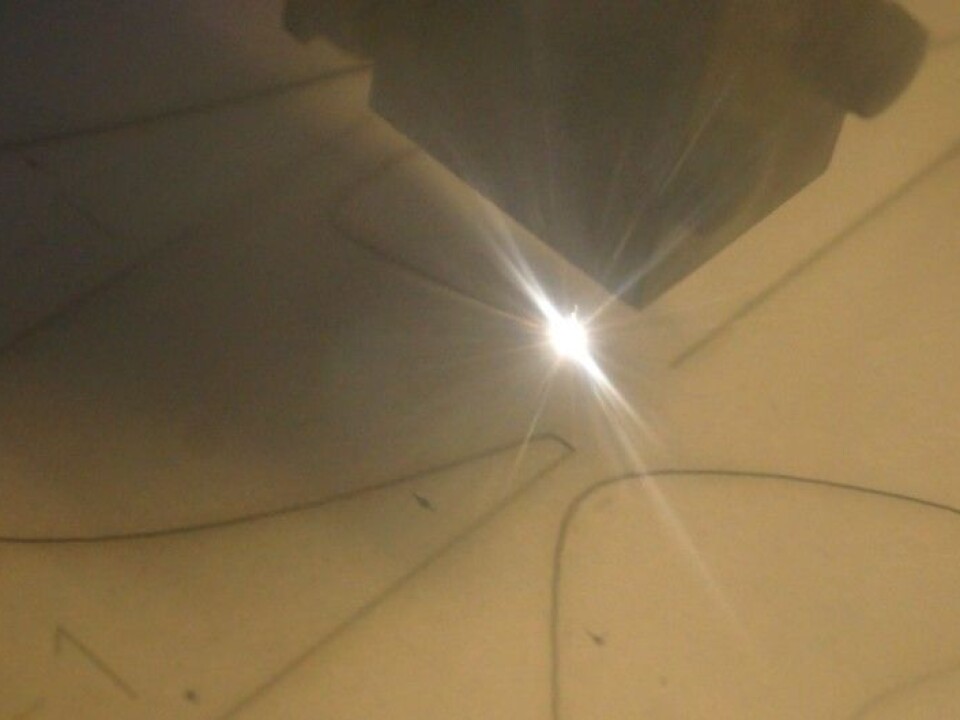

Matching printed numbers and points, Mikkelsen lays a huge cardboard sheet onto another printer that he uses for larger formats. This machine is a laser cutter that uses an intense light beam to sear out pieces of cardboard. Each piece is a layer of the model.

Mikkelsen manually glues the layers. An unsteady hand can mean starting all over again, but he finds it exciting to work using this semi-manual technique.

This technique offers new ways to create art. Another of Mikkelsen’s projects involved making 3D printouts of a whale vertebra that he then sanded and formed into an ergonomic computer mouse with hand tools. He repeated the alternating digital and manual processes, continuing to develop the form. This resulted in an elegant shape that fits comfortably in your hand.

Whale skull hyperfossil

“Reverse engineering” is yet another way to play with 3D software that was originally programmed for engineers. Worn out tools or machine parts are scanned, and engineers can then manufacture new replacements from the 3D models.

“In this process it’s important to find out what function the machine part has. You’re basically perfecting a broken form,” says Mikkelsen. He has transferred this idea to a beluga skull that he scanned in Ingebrigtsenbukta.

“What’s exciting with the whale skull is that it’s asymmetrical. Nature tends to strive for symmetry. So I wondered how people would experience it if I applied reverse engineering thinking and cleaned up the broken symmetry,” Mikkelsen says.

The result is a smooth, perfectly symmetrical skull. He calls the form a hyperfossil.

This and many other bone forms were on display at Galleri Svalbard in Longyearbyen earlier this spring. Mikkelsen was pleasantly surprised at how well received they were. “People liked being able to experience this history that is at once so close to them and yet so inaccessible,” he said.

------------------------------------------

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no

External links

- Trond Kasper Mikkelsen's profile

- dForm — digital fabrications lab. Web pages of the Oslo National Academy of the Arts

- 123D Catch — a free app that lets you play with photogrammetry