Several thousand people have been found in bogs in Europe. What kind of stories are found in 12,000 years of remains?

Many of them ended their lives in horrible ways, but there are many reasons why someone might have ended up in a bog.

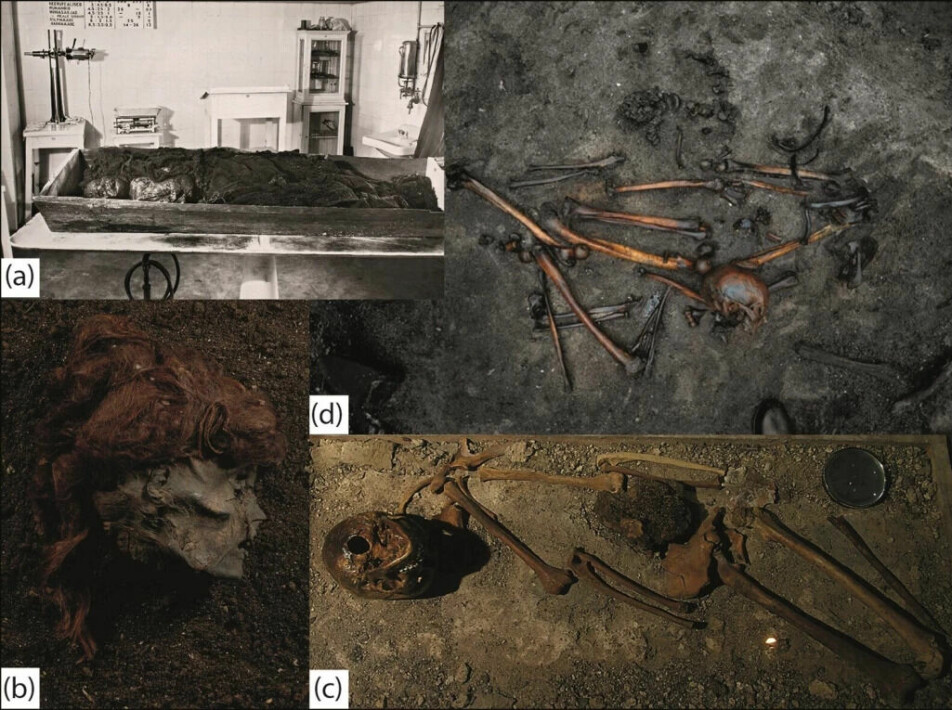

During the last hundred years, a number of very well-preserved human remains have been uncovered in bogs in Northern Europe.

One of the most famous discoveries was made in 1950. That’s when the police in Silkeborg, Denmark received a call that a body had been found in a bog.

The body turned up while someone was digging up turf in the area. The people who found it were certain that it was a man who had recently been killed, according to Museum Silkeborg.

The man had actually been murdered, but the murder took place around 2,500 years ago. He was probably hanged, and is now known as Tollund Man.

Digging up peat was relatively common work in countries with a lot of bogs and mires, since it can be used as fuel, among other things.

Unfortunately, the body of the Tollund Man was not preserved, and the exhibition consists of a model. Only the head remains, but it is very well preserved, and you can clearly get an impression of what this man looked like when he was alive.

2,000 found in Europe

The Tollund Man is just one of many very well-preserved corpses from prehistoric times that have been found in European bogs. Researchers know of around 2,000 individuals that have been found in bogs in Europe, but far from all of them are equally well preserved.

Some bog areas have particularly good conservation conditions, mainly due to special types of peat moss.

These types of mosses have bactericidal properties. This is a very important reason why some bodies hardly decompose in a bog, according to a new study in the journal Antiquity.

But these well-known bog bodies, where both skin and hair are preserved, represent only some of the human remains that have been found in bogs. Preservation conditions vary, and in some places only the skeletons are preserved. Both whole skeletons and individual bones from humans have been found in wetland areas.

In the vast majority of cases, archaeologists believe they are bones that were deliberately placed in the bog, according to archaeologist Grethe Bjørkan Bukkemoen.

Bukkemoen is an archaeologist and excavation manager at the Museum of Cultural History in Oslo. She 3helped lead the investigation of a bog skeleton that was found at Starane, a wetland site in Hedmark, in south-east Norway. The findings are described in a research article from 2018, published in the Journal of Wetland Archeology.

Often characterized by violence

Human remains that have been3 buried in bogs are a phenomenon found in large parts of Europe. The most famous bog corpses are naturally the best preserved, and they often originate from Denmark, the Netherlands, Belgium and the British Isles.

The well-preserved corpses often bear the mark of violence, and they have ended their days in a violent way.

But there are skeletal finds from many other countries, such as Norway. Because the skeletons are rarely complete, it is often difficult to determine why these people died.

A Dutch research group has now collected information on both skeleton and better-preserved corpse finds from bogs in northern Europe. They have systematized what is known from all of them, and have looked for patterns. The article was recently published in the journal Antiquity.

What does the research show, and why did people end up buried or deposited in bogs?

A comprehensive view

“This is a good study, and they provide a comprehensive overview of all findings over a long period and within a large geographical area,” Bukkemoen said to sciencenorway.no.

Bukkemoen emphasizes that this new overview includes both well-preserved bog corpses and all the bog skeletons that have been discovered in northern Europe.

She points out that the researchers have gathered a great deal of information about all the different finds, such as gender, context of discovery, age and cause of death. This provides a very good basis for further research, she said.

The earliest known human remains from Northern European bogs are more than 11,000 years old, but there are few finds dating from the next couple of thousand years. Then the number of finds picks up sharply, with the period with the most discoveries extending from around 3,000 to 1,000 years ago.

Around 180 different finds from this period have been uncovered. Most originate from present-day Denmark, although discoveries have also been made in northern Germany and Great Britain, among others.

The Tollund Man, the Grauballe Man, the Yde Girl and several other well-known mummified corpses from bogs date from this period.

Bukkemoen points out that most human finds in bogs are from the period beginning around 500 BC. But this new overview shows that the period with many discoveries seems to have started earlier and lasted longer than previously thought.

In the period between 1100 and 1900, the greatest number of discoveries have been made in the British Isles. Whether this is coincidental or can be linked to different samples or clear historical patterns is unclear. Perhaps future studies can shed more light on this question.

But one thing is clear. The well-preserved bodies from around 500 BC often bear evidence of violence and brutal deaths.

Hanging, beheading and unknown causes of death

An example is the Dutch bog corpse called the Yde Girl. This mummified body is dated from around the first century AD, and is very well preserved.

The Yde Girl was also found with a braided rope around her neck. This may be the remains of the execution method, meaning she may have been hanged, the researchers say.

Other bodies show signs of having been beheaded. In 1948, a mummified, severed head was found at Osterby, Germany. The hair was tied up in a knot which is still preserved. This head was wrapped in a skin, and the man had been hit so hard in the temple that it may have killed him, according to the researchers' record of the bog corpse.

Here there are clear causes of death, but the vast majority of remains found in bogs, especially the bog skeletons, have no clear cause of death. So why did they end up there?

Bukkemoen points out that bogs and wetland areas have been seen as important for various reasons.

“We know that notions of wetlands as the abode of various forces or as an entrance or passage to other worlds have a long history in North-West Europe,” she said.

The researchers say all the findings in the study can roughly be divided into a few categories:

Some people ended up in a bog due to very tangible reasons, such as drowning accidents. Others may have been victims of criminal acts and buried or hidden in the bog.

Some may have been sacrificed to supernatural forces, according to the researchers' interpretations. It could also be that people ended up in the bog as a kind of alternative burial or that they did not meet the criteria to be buried according to local customs.

Sacrifices in a Norwegian bog?

Grethe Bjørkan Bukkemoen points out that the bog skeletons that have been excavated from Starane bog in Hedmark in Norway may show signs of having been sacrificed.

The skeletons are mainly dated to pre-Roman Iron Age, the period from 500 BC. to around year 1. Bukkemoen said that cremation was the most common way of treating the deceased in this time.

Thus, the dead who ended up in the bog were treated very differently from what was usual.

“This is pretty exciting information about bog skeletons from this particular period,” Bukkemoen said. “We also haven’t found complete skeletons in bogs in Norway from this period.”

This might mean that certain bones were placed in the bog, while the rest of the body was cremated according to what is thought to have been the common custom.

Large quantities of animal bones are also found in different places in the bogs, Bukkemoen said. The bones were probably deposited by humans, and what was deposited in the bog varied over time.

Bukkemoen says that the conditions for preserving skeletons in the chalky soil in Hedmark are very good, but not in the same way as in the Danish bogs, where you can find preserved skin and hair.

It remains an open question as to what is hidden in other bogs in Norway and the rest of Europe.

Translated by Nancy Bazilchuk

Reference:

Roy van Beek et.al.: Bogs, bones and bodies: the deposition of human remains in northern European mires (9000 BC–AD 1900). Antiquity, 2023.

———

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no