Dead Sea Scrolls still conceal many stories

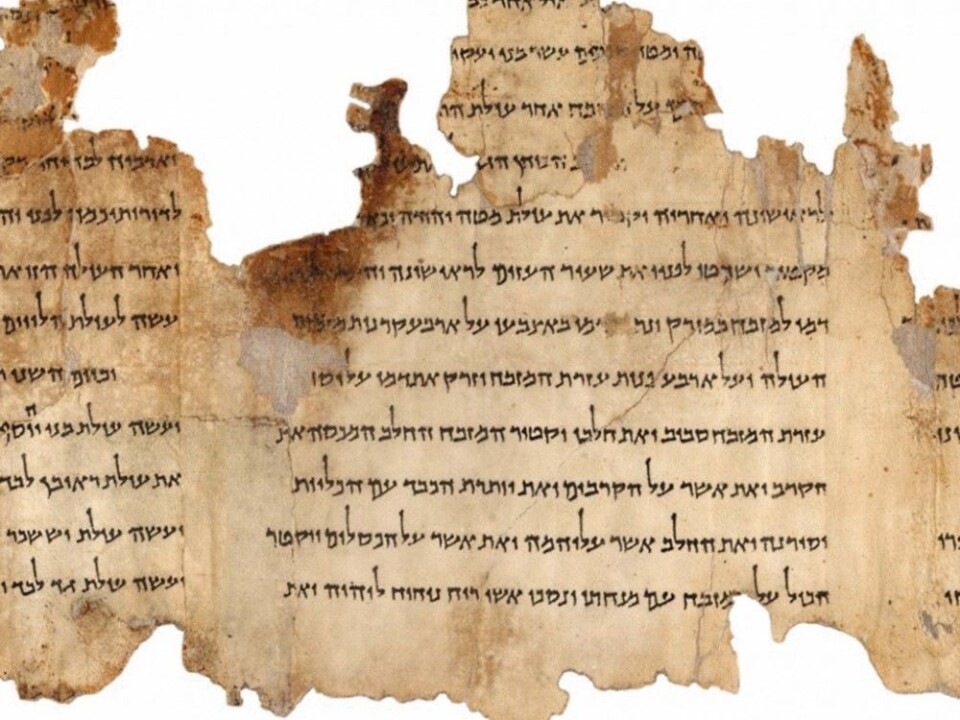

Norwegian researchers are trying to uncover more secrets about the mysterious Dead Sea Scrolls.

One of the most traumatic events in Jewish history occurred around the year 70 CE.

The Romans conquered Judea to crush the Jewish revolt that began in the year 66 CE. The Roman army travelled through the province, which is about where modern Israel and Palestine are today, and cracked down on Jewish settlements.

In the year 70, Roman legions sacked Jerusalem. The violence ended in a gruesome massacre of thousands of people within the city walls, and the Temple in Jerusalem – Judaism’s holiest site – was razed.

The Roman commander Titus had a triumphal arch built in Rome when he became emperor, and the arch shows the Romans carrying off their booty after plundering the temple.

This violent war is closely linked with the Dead Sea Scrolls – one of the most famous archaeological sites in the world.

Hidden in caves

As the Roman campaign raged in Judea, many religious texts were hidden – or forgotten – deep in desert caves by the Dead Sea, near the current border between Jordan and the West Bank.

The place is called Qumran, and in 1947 a Bedouin shepherd discovered hidden scrolls in a cave here, according to the Dead Sea Scrolls Digital Library.

Hundreds of different texts were unearthed in these caves around Qumran until 1956. They often lay well protected in sealed clay jars.

Fragments from several different scrolls have ended up in the Norwegian Schøyen Collection, a large private library that includes ancient manuscripts and religious texts.

The Israel Museum in Jerusalem houses the majority of the original scrolls.

Norwegian researchers have plunged into researching these fragments to find out more about the scrolls. How were they made, how old are they, and what is written on them?

Torleif Elgvin is a professor of Biblical and Jewish Studies at NLA University College in Oslo and has led the almost completed study project. A new article in the Norwegian journal Teologisk tidsskrift describes his research.

Nearly the entire Jewish Bible

But first, what exactly do these ancient scrolls contain?

Leather and papyrus scrolls written between 250 BCE - 65 CE contain parts of the Old Testament as well as a number of other Jewish religious writings.

Several scrolls also tell about Jewish sects that existed in Judea at this time. Most scientists assume that the Essene sect had a settlement and a library at Qumran Caves.

Other researchers, including John Collins at Yale University, argue that several sects probably used Qumran as a secret storage place to protect the writings from the Romans. Collins has written about the scrolls in the Huffington Post.

The Norwegian researchers have been trying to find out more about when and how some of these scrolls were made. What stories can ink, parchment and wrapping reveal?

Newer cloth

In addition to fragments, the Schøyen Collection includes a cloth wrapper that encased one of the best-preserved scrolls when it was found in a Qumran cave.

This scroll “is called the Temple Scroll, and it’s over eight meters long,” Elgvin told forskning.no.

“It contains a radically new version of Deuteronomy. The text is from the second century BCE, and the scroll is a copy from the first century BCE,” he adds.

Researchers used carbon dating on this cloth to determine its age. The cloth was made of linen that most likely was grown between 70 and 150 CE, making the linen cloth much newer than the Temple Scroll.

“This means that the cloth was woven after 68 CE, which was part of what surprised us the most,” says Elgvin.

The scroll with the new linen cloth was then probably placed in the cave after the First Jewish-Roman War in Judea between 66 and 73 CE.

“Someone must have been there right after the Romans came, and the question is, who the heck put the scrolls there?” Elgvin says.

Elgvin has some ideas.

He suggests that it may have been priests from Jerusalem, but it could also be that the Essenes didn’t disappear completely after the Roman attacks.

Who were the Essenes?

What do we really know about the people who lived out in the Qumran caves? Some of the scrolls describe Essene religious law, or halakhah.

“They were a strict and very religious part of Judaism,” says Elgvin. “They were conservative and puritanical, and they were very focused on ritual purity.”

This means that it was very important to wash before meals and religious rituals. The Essenes had dug out ritual immersion pools and built a dam to provide enough water for the Qumran settlement.

“They immersed themselves twice a day. But the water probably wasn’t changed in these pools, and it couldn’t have been particularly hygienic for all the men to wash themselves in the same water for months,” says Elgvin.

Graves that have been found in the Qumran area show that the men died very young, even compared to other men of that time. Very few reached their forties, which may have been due to the unsanitary conditions, according to this study.

They had made a latrine for the whole settlement where they buried the faecal matter in desert soil. The problem is that micro-organisms and bacteria continue to live underground, but they die in the sun. Thus, the Essenes created their own toxic waste space.

“If you walk through this area, and have a cut on your foot ....,” says Joe Zias in a press release, one of the researchers behind the study that was published in 2006.

But in spite of hygienic troubles, the Essenes and the other Jewish groups may have been influential and wealthy.

Rich and prosperous culture?

Based on analyses of the parchment and ink that were used for some of the scrolls, Elgvin and his colleagues believe that the scrolls can give clues about the scroll-makers' life and culture.

One of the fragments analysed originated from the Great Isaiah Scroll, another huge scroll. It contains the oldest version of the Book of Isaiah that exists, and the scroll was created around 90 BCE. The Book of Isaiah is part of the Old Testament and the Jewish bible.

This and another fragment from a scroll that was stored in the same location have been analysed.

The parchment it was written on tells us something about the people who commissioned the scroll.

The parchment was made using advanced methods that we didn’t know people were familiar with at that time, says Elgvin.

Goatskin used for parchment was treated with silicon, calcium and aluminium as it was scraped and stretched. The result was a "pale creamy parchment," as the researchers describe it.

“This was perhaps the best parchment available anywhere, and we find it in a small corner of the desert,” says Elgvin.

The research group’s interpretation of this is that the people who used and hid these scrolls in Qumran were relatively wealthy. The researchers think they played a central role in the region and probably were not a peripheral group who lived in a secluded part of the desert.

The researchers also found lead in the parchment. This is a trace substance from the production process, which required large amounts of water to make parchment from animal skin. The lead may have come from water pipes in Jerusalem. They were laid by the Romans, who used lead in the pipe structure.

“The scrolls must have been made in central locations, and then been moved out to the countryside,” says Elgvin.

The researchers also reconstructed texts from the fragments, and did other mineral analyses of the parchment.

------------------------------------------------

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no