Inca kids drugged before being sacrificed

Child corpses found on the Llullaillaco Volcano in Argentina are the world’s best preserved mummies. Analyses reveal that in the run-ups to their deaths 500 years ago, they had been given intoxicants for periods up to a year.

Denne artikkelen er over ti år gammel og kan inneholde utdatert informasjon.

Three child mummies, a girl aged 13 and a boy and girl aged four or five, were discovered in 1999, entombed in separate ritual graves, a few metres from the peak of the Llullaillaco Volcano on the border of Argentina and Chile.

They had been undisturbed for 500 years, frozen in the dry Andean climate at an elevation of 7,000 metres. The corpses were so well preserved that they could almost be mistaken for children who were only taking a siesta.

Scientists understood immediately that the children had been sacrificed. The Inca practice of sacrificing children for religious purposes is well documented. The rite is called capacocha.

The corpses from Llullaillaco have been thoroughly examined. One showed they had been fattened up before being sacrificed.

But they were given more than just an abundance of nutritious food, scientists have found. A new study recently published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States shows that alcohol and coca leaves were given to the children prior to the ritual, perhaps to make it easier on the victims and their families.

Length of hair

Researchers at the UK’s University of Bradford sought to reconstruct what they could of the last year for the trio prior to their sacrifice.

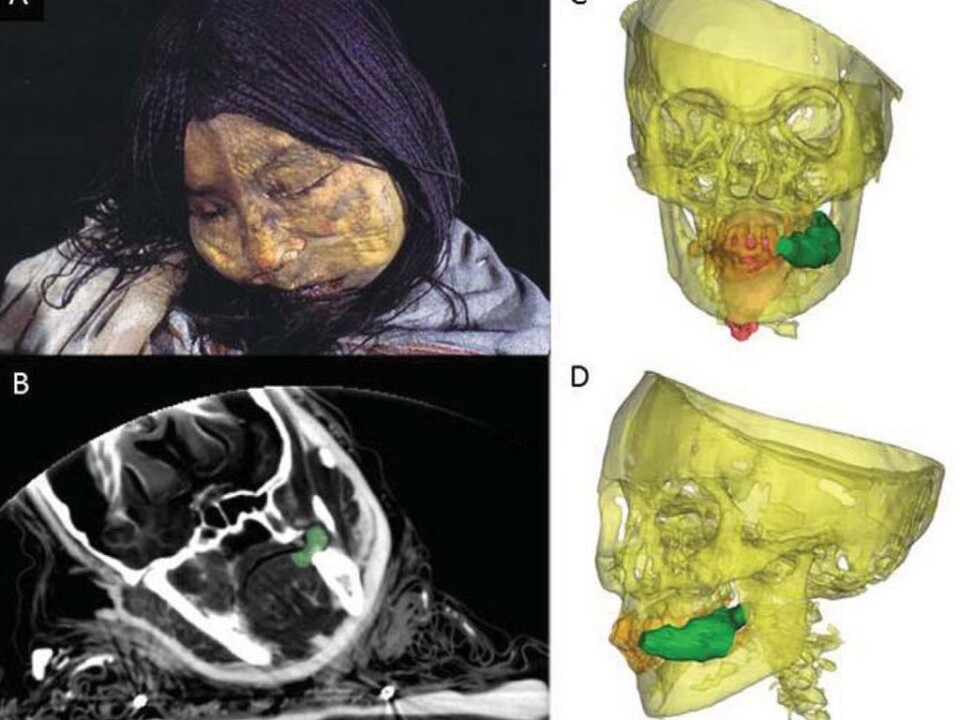

"We had the electronic CT scan files sent to us, so we could make a virtual autopsy of the child mummies,” says Professor Niels Lynnerup, of Copenhagen University’s Department of Forensic Medicine.

”Denmark ranks among the world’s elite with regards to this type of 3D visualisations, and that’s why archaeologists and researchers from other countries turn to us for assistance in analysing the mummified material.”

The researchers were keen to find out if any stimulants or intoxicants had been used, which might suggest a lengthy ritual, culminating in the children’s deaths.

An international team of scientists from Denmark, the UK and Argentina conducted the new analyses, in which they examined findings from the tombs, biochemical markers in the scalp hair of the mummies and x-rays. They were particularly interested in the older girl, La Donchella, or the Maiden.

Her hair was used as a time line, in which one centimetre was equated with about a month of the girl’s life.

By analysing her tightly braided hair, the scientists were also able to detect how much alcohol and coca she had used in various periods up to the time of her death.

The ritual begins

The hair analyses show that her diet suddenly improved considerably in the year before her demise. The scientists think this probably marks the beginning of the ritual process that led to her death.

The results show the girl started to use alcohol and coca in small and moderate amounts. Dosages peaked six months before she was sacrificed.

Then the usage declined for a period and spiked again during the last part of her life.

The researchers wrote that this pattern indicates that intoxication was used to make her more compliant in a ritual that would culminate in her death.

When La Donchella died – probably of exposure – up on the peak of Llullaillaco, she had been drinking a lot of alcohol for several weeks. A wad of coca tobacco lodged between her teeth indicates she had been chewing it immediately before her death.

Supernatural intoxication

The highly valued alcoholic beverage chicha was made from maize and used ritually by the Incas.

The Incas probably believed an intoxicated person had channels to the gods. The researchers think this was probably the reason the sacrificed children were given alcohol. Coca was also a revered substance.

But there could have been multiple reasons for the use of intoxicants in the three children the year before death.

The researchers speculate in their study that these substances could sedate and muddle the children, an aspect that shouldn’t be underestimated.

Who were they?

The analyses also showed that the children were given different treatment. The 13-year-old girl had drunk considerably more alcohol than the two younger children. She had meticulously braided hair and a feathered headdress.

The young girl’s hair was more dishevelled. And the boy’s hair was full of nits.

The 13-year-old girl must have been a so-called Acllas, a selected woman who wasn’t considered a child in her culture.

Such women were isolated from their families around adolescence and taken into the care of priestesses and either wed to noblemen or used in human sacrifices. These women were trained in the art of weaving and fermenting chicha.

The sudden transition to a richer diet indicates she lived an elite life in her final year.

A signal instilling fear

It was not unusual for the young victims of capacocha to be placed high up on conspicuous spots in the terrain. The researchers write that these sacrifices could be linked to the Inca’s territorial expansion and domination of other tribes in the century before the Spanish invasion.

The carefully staged sacrifices of children gave immediate advantages to the groups the children came from.

At the same time, it must have been frightening and instilled a certain climate of dread and terror. The researchers refer to notes on child sacrifice made later by the missionary Bernabé Cobo, in the mid-1600s.

Cobo wrotes that the parents who had to give up their children were not allowed to show any signs of grief, which would have been totally unacceptable.

In fact, he wrote, the parents were supposed to behave as if they were glad to have given away their son or daughter.

”We know with great certainty from historical sources that the children were sacrificed,” says Lynnerup.

“And now our scientific analyses of these incredibly well-preserved child mummies give us new information about what happened to the children before they died.”

---------------------------

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no

Translated by: Glenn Ostling