Spying on seals with videocams and sensors

Researchers are equipping seals with cameras and sensors to find out exactly what they do down in the deep blue sea.

Denne artikkelen er over ti år gammel og kan inneholde utdatert informasjon.

When it comes to mammalian denizens of the deep blue sea, Norwegian researchers have some knowledge about where the animals congregate and how deep they dive.

“But the most important question is, what are seals and whales doing at any given time? We still know very little about that,” says Martin Biuw, a researcher at Akvaplan Niva in Tromsø.

Biuw manages a project that will equip seals with new gadgets so that researchers can follow their every move - well, almost.

Mobile phone technology

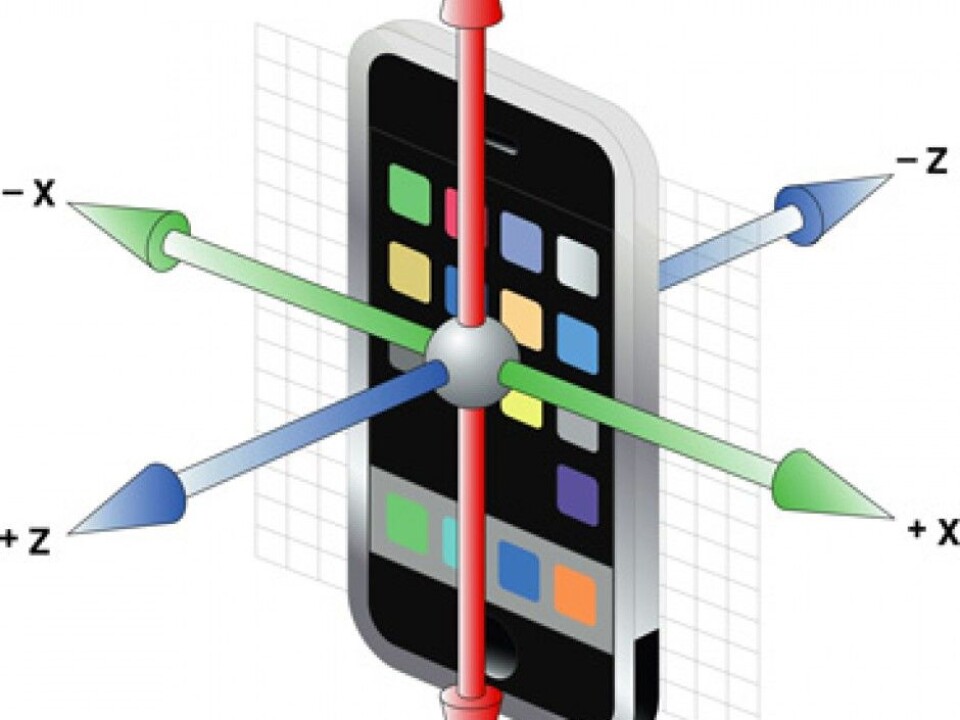

The technology is the same that anyone with a smart phone walks around with in their purse or pocket. If you have a sports app on your phone it does the same thing.

A little chip with an accelerometer collects information about body motion and changes in velocity and direction.

This chip will soon be helping scientists figure out how much energy the seals expend on a daily basis, and how much energy individual seals store in their fat. The researchers can also determine where the seals are finding food.

Scientists hope to see what the animals are eating with the help of little cameras mounted on individual seals.

Lacking knowledge

Seal counts reveal a population of about 1.4 million in the West Ice, a patch of sea between Greenland and Norway’s volcanic island, Jan Mayen, which is frozen in the winter. Another 600,000 seals live in the East Ice, north of Russia’s Kara Sea.

Fishermen and environmentalists quarrel about how much fish are eaten by Greenland seals and other seal species.

“We currently have fairly good information about the number of seals in the North Atlantic. But we don’t know enough about how much energy each seal needs and thus how much it eats,” says Biuw.

“Although the Norwegian Institute of Marine Research and the University of Tromsø have provided estimates, the numbers are uncertain. And conditions can also change from year to year,” he said.

“We don’t know much for certain about what Greenland seal most like to eat, whether it is polar cod, smelt, krill or something else. And we don’t know how their diets change seasonally and from one year to the next.”

Research voyage to the West Ice

The old way of studying Greenland seals has been to go them – sail a ship to the West Ice between Greenland and Jan Mayen.

Although much of this research has been compelling, it only provides a static picture of what seals were eating right there and then. Their daily fare and energy expenditures can be quite different when they are out at sea.

Scientists have also made use of satellite transmitters to monitor the migration of seals and their diving habits. But this technology provides only limited information about what the animals do when they are below the surface.

Down in the depths soon

If scientists can successfully confirm that their technology works in a test run outside of Tromsø, in a year or two they can attach the same gear to wild seals on the ice off Greenland.

The instruments attached to the seals on the Arctic need to collect data and transmit it by satellites. But the amount of data that can be sent this way is quite limited. Advanced calculations have to be made in the instrument to keep the digital load of the transmissions to a minimum. Seals are being studied at test facilities outside of Tromsø to aid development of software and methods for calculating and compacting data.

The scientists are certain that if it works on seals, the technology will also work on whales.

Test lab on the outskirts of Tromsø

Test runs are being made with seals swimming around in a salmon farming pen in Kaldfjorden outside of Tromsø.

Biuw and his partners at the University of Tromsø have been thinking for years about setting up a lab like this for seals in Norway.

Now the lab is finally up and running.

“Building these test facilities turned out to be a much bigger job than we expected. But now we have a unique laboratory out in the ocean. We have already received lots of enquiries from seal researchers around the world who would like to use it.”

Gauging oxygen consumption

The new lab has already helped researchers learn more about how a seal’s swimming behaviour is affected by the amount of body fat it has stored. They fitting seals out with a vest that contained either floats or weights to simulate fatter or slimmer seals.

“Seals are like us. If you are fat you need to work hard to dive down but you float easily up again,” Biuw said. “If you are skinny you can easily descend but it is harder to float back to the surface.”

The researchers see this clearly in the data from the activity monitor.

The new test facility also allows them to gauge the oxygen consumption of a seal during its underwater journeys.

A normal dive by a Greenland seal lasts five to fifteen minutes. But they can stay down for up to a half hour before they need to surface for oxygen.

Seals don’t fill their lungs with air before diving like we would do. On the contrary, they blow out lots of the air in their lungs, in part to make it easier to dive and stay down.

They store the oxygen they need for the dive in their blood and muscles.

Face recognition in the deep blue

Data will have to be relayed to satellites when the new technology under development in North Norway is attached to seals or whales in the wild.

In addition to information about energy consumption and body condition, the researchers want to know what and how much seals eat. They have an additional project underway in which cameras will capture images of the prey.

“But like the activity data, the photographic data is much too massive to be sent from an animal down in the sea up to a satellite,” says Biuw.

So the researchers plan to use advanced algorithms for pattern recognition, like the ones used for face recognition in cameras and mobile phones.

“These algorithms are used with the pictures right away and hopefully tell us whether the seal is catching, say, krill, smelt or polar cod,” Biuw said.

“If this project gets support from the Research Council of Norway, scientists at the Norwegian Computing Center will help us with this part. It will be labour intensive and pose a real challenge.”

“It can’t be denied that research is a risk sport,” Biuw said.

----------

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no

Translated by: Glenn Ostling