Apps open new urban dimensions

Architecture is more than building design. The project YoUrban uses digital technology to reveal layer upon layer of action, interaction and future visions.

Denne artikkelen er over ti år gammel og kan inneholde utdatert informasjon.

You stand on the pavement with your mobile raised to eye level. The app Layar turns your display into a digital window into a hidden aspect of the city, otherwise invisible.

You see the block of flats before you on the display. A large grey circle hovers in front of it.

The circle tells you that the flats built new balconies in 2010. A tap on the display takes you to the web pages of Oslo’s Department of Urban Development.

Augmented Reality

This is known as augmented reality, or AR. Visual information is superimposed on concrete images, seen from the same angle.

The app shows you roof terraces that have been added, information about fire damage or where trees have been chopped down illegally. The city is suddenly visible in a new way – it takes on an extra dimension.

Urban planning with bubbles and lines

The AR app Layar is available as a free download for androids and iPhones. The program that uses Layar to display data about construction issues in Oslo is called PlanAR.

It was produced by Even Westvang of the Norwegian firm Bengler.

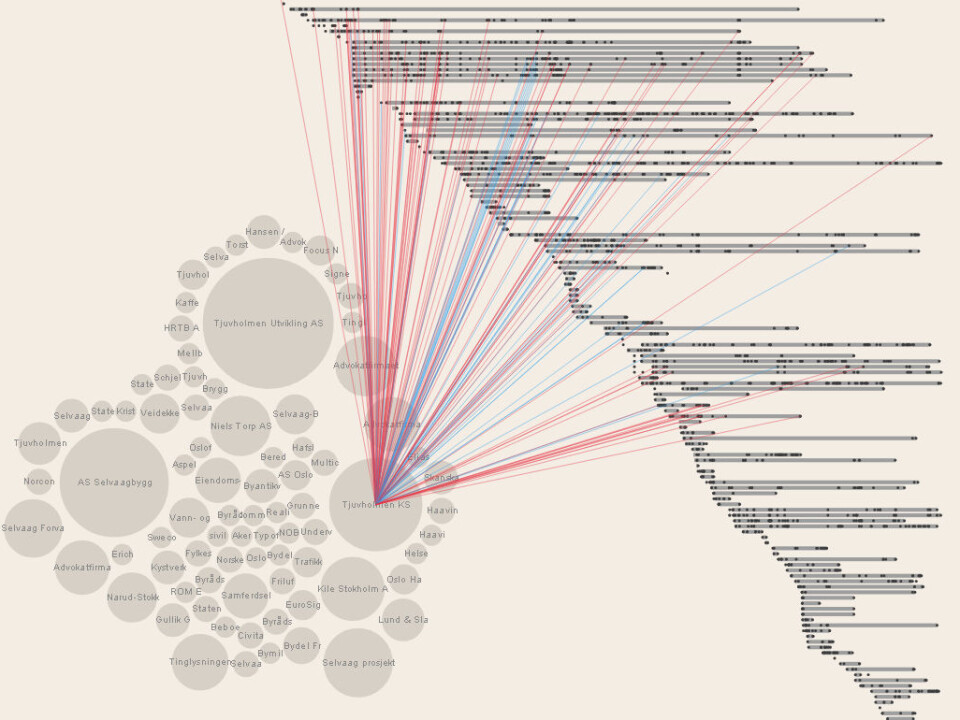

In another digital image of Oslo, we hover high above a three-dimensional map via the web browser. In the upper left corner the days, months and years count into the time ahead.

This is the program Planimator, also from Bengler. Various sized bubbles appear in different parts of the city. They indicate construction projects with a time dimension added.

Data scraping

Westvang explains that the information was extracted from the standard website of the Department of Urban Development and added to a database.

These data are not really structured to meet the requirements of a database. So Westvang used a series of assumptions about the organisation of the information. This process is called data scraping.

“To avoid an overload of the Department’s IT hardware, the scraping was done slowly, requiring a couple of weeks of uptime,” says Westvang.

The data had to be purged of mistakes. Westvang says one of the firms in the registry had been spelled in 250 different ways. He cites this as a reason why public officials shouldn’t be satisfied with simply establishing portals. They need to provide data resources that are readable by computers.

Revealing the invisible city

These programs, and more of their kind, have been developed in collaboration with the Oslo School of Architecture and Design (AHO). At its Institute of Design, the people behind the project YoUrban are researching ways to make the invisible city visible.

The invisible city is spawned by its inhabitants. Social patterns, the way people use the city to interact, are revealed.

Even cultural patterns can be disclosed – the way people use the city to express themselves, their experiences, dreams and expectations.

Use of inhabitants

“We want to design more than the physical structures. We want to create digital services that can be used by residents to exchange views and affect social and cultural patterns,” says Andrew Morrison.

Morrison is a professor at AHO’s Institute of Design and leads the YoUrban Project.

Streetscape

Another app for smartphones was developed by EngageLab, a team of developers and designers at the University of Oslo’s Faculty of Education Sciences.

Streetscape shows you where you are on a three-dimensional map of the city, using the open solution OpenStreetMap.

You can add photos or text that is relevant to your position. You can communicate your contributions via Facebook.

The pictures and texts combine to make what the developers call an urban map. They were inspired by a method developed by the international architectural firm Chora.

Their method involves the use of IT and mobile media to amass as many contributions as possible before construction projects commence.

The people who are affected can join in the decision-making process through digital discussion forums.

“The YoUrban Project doesn’t only involve the designing the invisible city. It also maps the daily life of this city, interpreting how people live and experience it,” explains Morrison.

Practical use

He stresses that the apps that have been developed for mobile phones and web browser are not experimental prototypes. Many of them are currently downloadable or are found on open websites, fully functional.

“We work with great designers and programmers. These solutions have to be fully functional and useful,” says Professor Andrew Morrison of AHO.

Translated by: Glenn Ostling