Wind erosion has created a sculpture park in Antarctica

Hundreds of thousands of years’ worth of wind have created a unique rock sculpture park near the Norwegian research station Troll in Antarctica.

Unusually strong winds, sand and ice crystals, large blocks of rocks, and hundreds of thousands – perhaps even millions – of years.

The results have created a nature’s own sculpture park, on a slope just behind the Norwegian all-year research station Troll in Antarctica.

In their blog The Antarctica Geologists (link in Norwegian), Researchers Synnøve Elvevold from the Norwegian Polar Institute and Ane K. Engvik from the Geological Survey of Norway share photos and stories from their current expedition in the challenging landscape.

The wind in the area called Jutulsessen, where the research station is located, can come up to the level of hurricanes, the geologists write. The station has measured winds over 60 metres per second, with windgusts up to 90 m/s. The average temperature is -18 degrees.

The shapes and cavities on the gneiss and granite rocks have their own geological names: ventifact and tafoni.

A ventifact is a rock that has been shaped by wind-driven sand or ice crystals, while tafoni are small to large cavity features that can develop naturally.

“These are the structures that one in the art world would describe as organic and soft shapes, and which have so magnificently created sculptures in nature’s own show”, the two researchers enthusiastically write.

The mountainous areas in Antarctica get little rainfall, they are a polar desert. This rough climate doesn’t allow for plants to grow, Elvevold and Engvik write. “But this gives us a much better impression of the geology”.

Particle by particle

The erosive power of the wind is of little importance compared to moving water and ice, the geologists write.

But in the polar deserts with strong winds, little rainfall and average temperatures around – 20 degrees, the conditions are just perfect for the creation of ventifacts.

The wind carries sand and ice particles that polish, grind and erode when they collide with the rocks.

During storms and hurricanes, sand and small rocks will be flung into the air and hit the rocks.

Fine sand can travel quite far before hitting a rock.

The heaviest sand grains will be lifted less high from the ground, and will thus have the largest eroding impact further down on the rocks.

“Every time the rock is hit by a particle, microscopic shards are split off. After countless such hits, the result is a polished look”, the researchers write.

“We’re basically talking about sandblasting stones!”.

Perhaps surprisingly, also ice particles can erode stone. When near the melting point, ice is softer than a fingernail, but hardens as it gets cooler. Around minus 40 degrees, ice particles are as hard as the mineral quartz.

- MORE ON ANTARCTICA: The "missing link" that triggered the ice ages

Updating our geological knowledge of Antarctica

Elvevold and Engvik are part of a team of researchers that finally reached Antarctica in mid-January, having first spent 39 days in Covid quarantine.

Their task is to create a geological map by examining the mountainous areas in Queen Maud Land, a region of Antarctica claimed by Norway as a dependent territory in 1939.

“The current knowledge about the geology in Queen Maud Land is limited and there is therefore a need to increase our competencies in this field”, the researchers write in their blog.

A geological map shows the share of various types of rock and sediments, as well as other geological information such as the age of the rocks, as well as the sequence of various geological events such as deformation, metamorphosis, intrusion of magma and erosion.

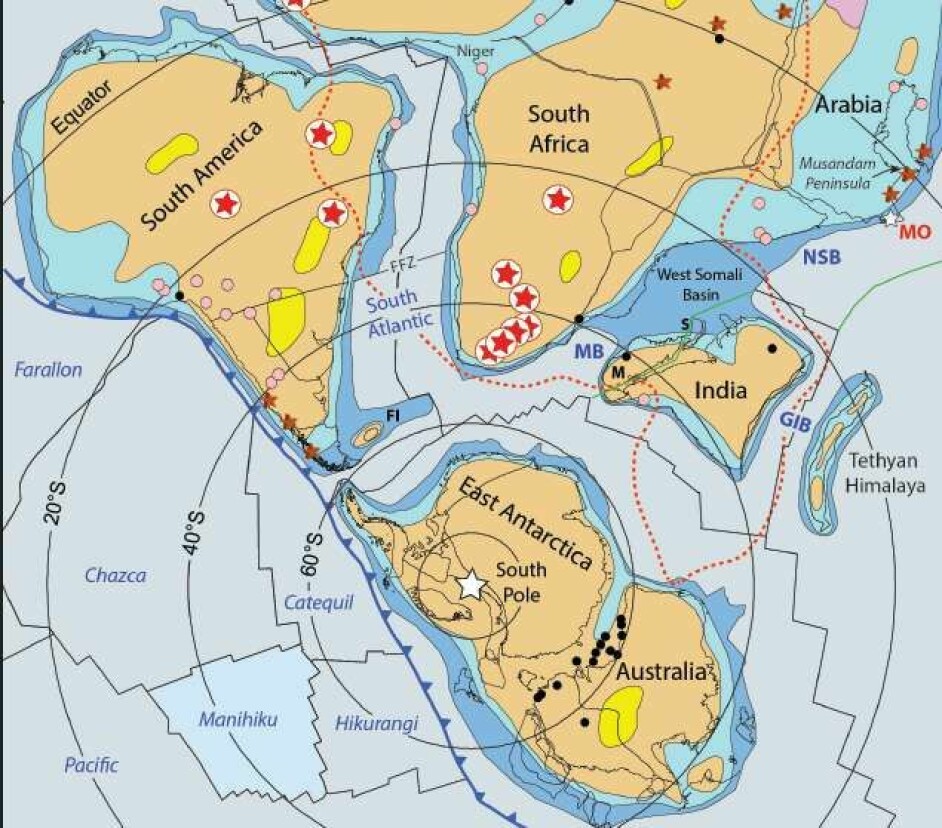

Remains of old mountain ranges show that Queen Maud Land has been part of two so-called supercontinents, when most of the earths continental blocks formed a single large landmass.

The areas that the geologists will visit during the expedition were mapped in the 1980s. However, the researchers write, 30 years later, we have a new understanding of geological processes, and thus new examinations need to be undertaken.