The riddle of rodents

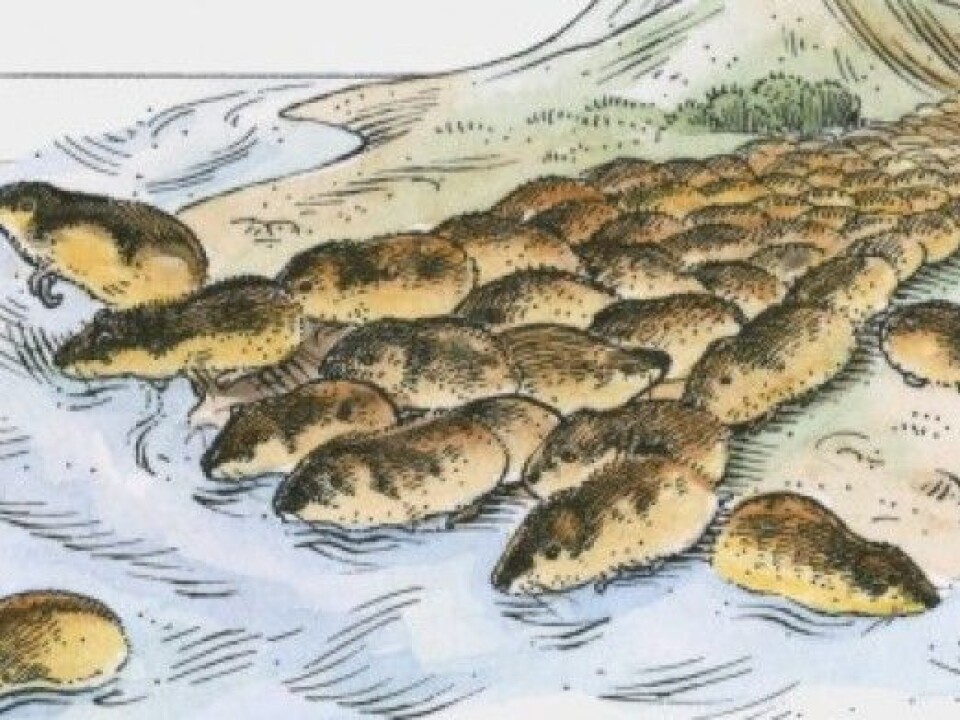

Last year so many rodents roamed Norwegian forests that residences were overrun, from mountain cabin attics to house basements. This summer in southern Norway, rodent numbers have plummeted to roughly one-hundredth of what they were just a year ago. Yet no one really knows what’s powering these enormous population swings.

Denne artikkelen er over ti år gammel og kan inneholde utdatert informasjon.

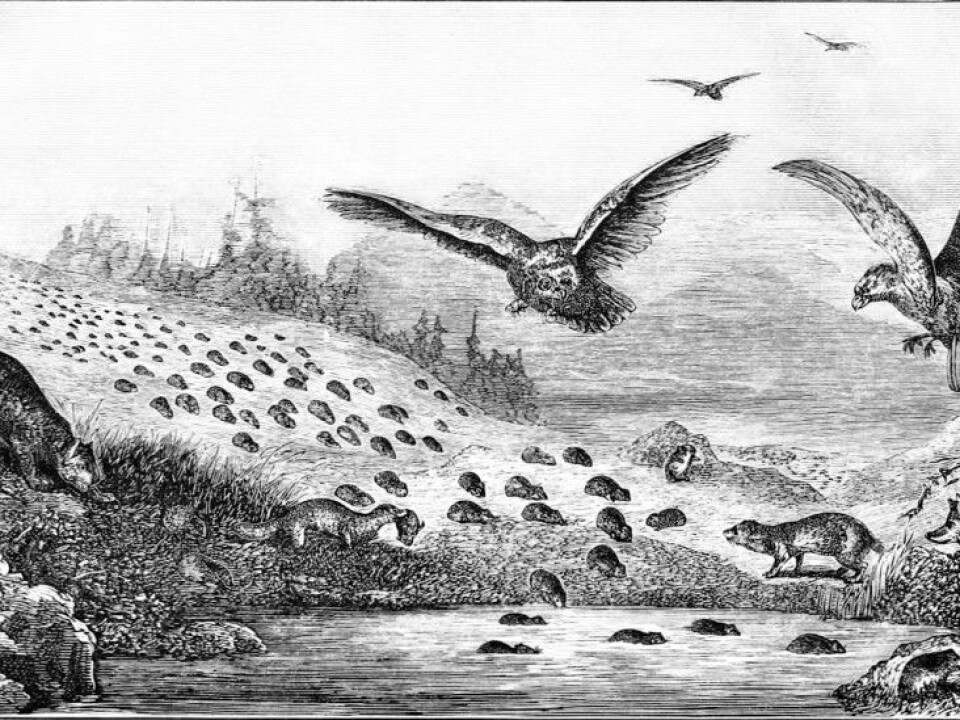

It has been a very bad year to be a fox, a raptor, an owl, a snake, a stoat or any other member of the weasel family in Norway. That’s because the mice and voles that feed these critters have nearly disappeared from Norwegian fields and forests, particularly in the southern part of the country.

Norwegians are so accustomed to these big population swings that their language has distinct words to describe the trends: “musår”, meaning a year when mice populations explode, or “lemmenår”, or lemming year, when lemming populations go wild.

Even non-Norwegians know of the huge population swings that lemmings undergo, thanks to a 1958 Walt Disney documentary called “White Wilderness”, which shows hoards of lemmings committing suicide by jumping off a cliff. This, however, was an event staged for the movie to dramatize a myth and absolutely never happens, researchers agree.

But other than that, there is little agreement as to what fuels the huge booms and busts in Norway’s rodent populations. Instead, researchers have a range of hypotheses to explain this strange cycle plays out every three to four years.

The big three

Norwegian biologists who are experts in rodent population dynamics offered three different but standard hypotheses to explain what drives the cycles.

The first is that when rodents abound, predators such as foxes, birds of prey and weasels multiply profusely. All those new predator mouths to feed cause a crash in the prey population.

The second could be called the food or grazing hypothesis: As grazing pressure builds on the plants, like blueberries, that rodents eat, the plants produce toxins to defend themselves. This essentially poisons the mice and voles that try to eat the plants. Some sort of similar mechanism would explain what happens to lemmings in the mountains.

The last hypothesis relates to climate: When snow depths and cover are low, small rodents are much more exposed to predation. Winter survival can have a huge impact on population numbers.

A fascinating question

“These large natural fluctuations have always fascinated humans,” says Lasse Asmyhr, a researcher at Hedmark University College’s Evenstad campus, in southeastern Norway.

Asmyhr is part of a team that is tallying animal populations and studying in the Evenstad area to attempt to uncover some of the mechanisms behind the big population cycles.

The researchers will not be able to provide a definitive answer to why rodent populations boom and bust. But their data show the importance of both the plants that that feed the rodents, and the predators that eat the rodents.

What they don’t know is if the system is driven from the top, by predators, or from the bottom, by plants. Asmyhr and his colleagues also say that rodents themselves might somehow be the drivers of the swings.

A combination of hypotheses

Jørund Rolstad from the Norwegian Institute of Bioeconomy Research (Nibio) says that the answer probably lies in a combination of the various hypotheses.

“Looking at the various explanations in context, we know that there must be a complex pattern behind these large natural population fluctuations. We know that snowy winters can give rise to more rodents, because the snow cover protects them from predators,” Rolstad said. “But snow cover does not fully explain why rodent populations crash so completely, as we experienced in southern Norway last winter.”

Rolstad mentions a fourth hypothesis that is also being discussed among biologists, called social regulation.

“When there are as many mice as were found in Norway last autumn, the animals are stressed. There are simply too many of them,” he said. “This inhibits reproduction, so the rodents simply do not have babies.”

No simple answer

Other researchers name seed crop, food quality and factors such as high and low pressure systems and cosmic rays as possible factors controlling rodent cycles.

But Rolf Anker Ims, a professor at UiT The Arctic University of Norway who is widely seen as the doyen of small rodent research, says most of the data support the predator hypothesis.

“There have been a ton of hypotheses as to why we get these rodent population explosions,” he said. “Most of them we can forget, except for the predator hypothesis and the food hypothesis.”

Ims says mathematical models show that the predator hypothesis is the most likely to be true, even though scientists do not yet have data that fully support the theory. There is also some support for the food hypothesis, he said.

“These two hypotheses appear to have the greatest explanatory power, so that is where we should focus our efforts,” Ims said.

-------------------------------------

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no