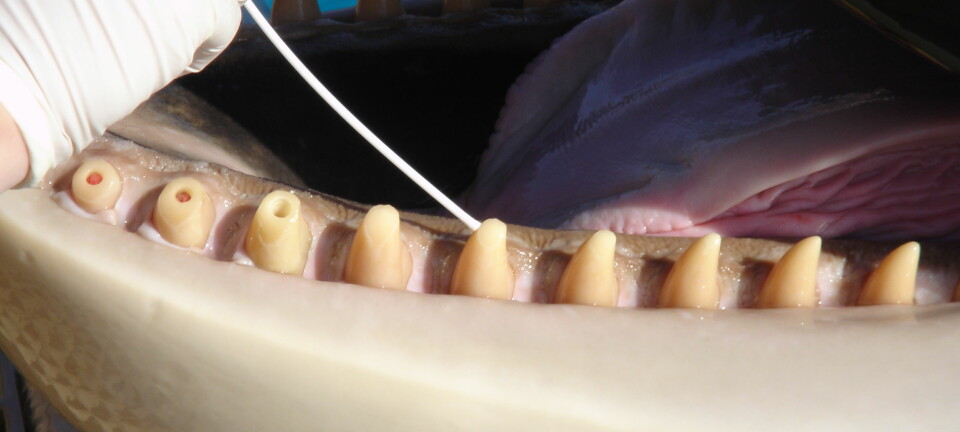

Scandinavian otters full of contaminants

The Scandinavian otter is full of high concentrations of environmental contaminants that were banned years ago.

Denne artikkelen er over ti år gammel og kan inneholde utdatert informasjon.

Otters in Sweden and Norway are contaminated with high amounts of environmental contaminants, particularly a compound called perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS). These concentrations are not dropping, despite an international ban on the substance.

Laboratory tests of rats and mice have shown that PFOS and similar toxic compounds are harmful.

Researcher Urs Berger of Stockholm University is one of the scientists behind a new study of the contamination in otters. He says the levels of PFOS in these playful sea mammals are among the highest ever found. Concentrations at this level have only previously been measured in polar bears.

He is concerned about the findings and compares them to concentrations detected in rodents subjected to lab tests.

“We are now finding the same concentrations as are used in lab experiments and that cause acute damage,” says Berger.

Severe effects

Experiments with PFOS on mice and rats led to liver damage, weight loss, a decrease in fertility and increased mortality.

Berger says it is hard to compare results from lab tests with the effects on wild animals in nature.

The effects will vary from species to species and there are no studies to date that show how PFOS and similar environmental contaminants affect otters.

But there are certainly reasons for concern. The long-term impact can be much more detrimental than any effects monitored short-term.

Phased out

PFOS has been used in products including stain removers, textiles, fire extinguishing foams as well as in numerous industrial processes. The compound does not deteriorate readily, so it remains in the environment for a long time, and can work its way up the food chain.

Its harmful effects have been known for years.

The former major PFOS producer, the US-based firm 3M, decided in 2000 to discontinue its production. The EU has stopped nearly all import of products containing the substance.

Norway has banned it in fire-retardant foam, textiles and impregnation products.

Despite such efforts, the study shows that levels of the chemical in Scandinavian otters have not diminished in keeping with the chemical industry’s phase-outs of its production.

The researchers compared frozen tissue samples of otters from 1972 to 2011 in their study and did not detect any decrease in the banned chemical. In fact, the researchers found that levels had increased.

In addition to PFOS, the researchers looked for related toxic compounds.

Still rising

“The levels of most fluorated environmental toxins are currently rising despite the phasing out of some of these chemical substances as early as 2002,” says Berger.

This indicates that the environment is contaminated with PFOS and similar chemicals and that living organisms have a hard time getting rid of them once they start accumulating them.

Many other environmental toxins accumulate in fatty tissues. But PFOS and related toxins bind with proteins, not fats, so they are primarily stockpiled in the blood and liver.

This makes them more biologically active than if they were stored in the fat of an animal.

Unknown source

Where does this environmental contaminant come from? The researchers would like to know. It's possible that one sources may be from products that were bought, used and discarded before the bans were implemented.

The chemicals may be coming from rubbish tips and water processing plants. Or they could be circulating with ocean currents. Otters eat lots of fish on the coast and in lakes.

Berger says the China is still producing PFOS, but the total world production has decreased.

--------------------

The study is a collaboration between the Swedish Museum of Natural History, Uppsala University, Stockholm University and Norwegian Institute of Nature Research.

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no

Translated by: Glenn Ostling