Researcher explains why you should choose whole salmon over fillets

Many salmon have been sick – often multiple times – before they are slaughtered.

When choosing between salmon fillet and a whole salmon with skin and bones, researcher Trygve Poppe has no doubt about what he would choose.

A large proportion of Norwegian salmon have been sick – often during multiple periods – during their short two-year lifespan.

Some of them are so sick that they would not survive the journey to the slaughterhouse. Therefore, it has become more common to slaughter the fish in the pens, according to Poppe.

"Farmers have realised that it's better to slaughter the salmon out in the pens, as this prevents many from dying on the way to land," Poppe tells sciencenorway.no.

He is a former professor at the Norwegian School of Veterinary Science and an expert on fish health.

"A lot of the fish are in such poor condition that they would probably have died after just a few hours or days anyway," he says.

Nevertheless, they end up as human food.

The difference between salmon fillet and whole salmon

In the aquaculture industry, salmon are categorised as 'production fish' and 'superior fish.'

Production fish are fish with sores, deformities, gross treatment errors, or other defects according to the Norwegian Food Safety Authority (link in Norwegian).

"This is fish that cannot be sold or exported as whole fish," says Poppe.

For production fish to be sold as human food, the defects must be corrected, according to the regulation on fish quality (link in Norwegian). This means that wounds and injuries are cut away.

As a result, production fish are sold as salmon fillets, salmon cakes, salmon burgers, and other fish products.

Superior fish, on the other hand, are of the highest quality without visible defects or flaws.

"This is fish as you want it to be: healthy, nice, and fresh in every possible way," says Poppe.

Where does the healthy fish come from?

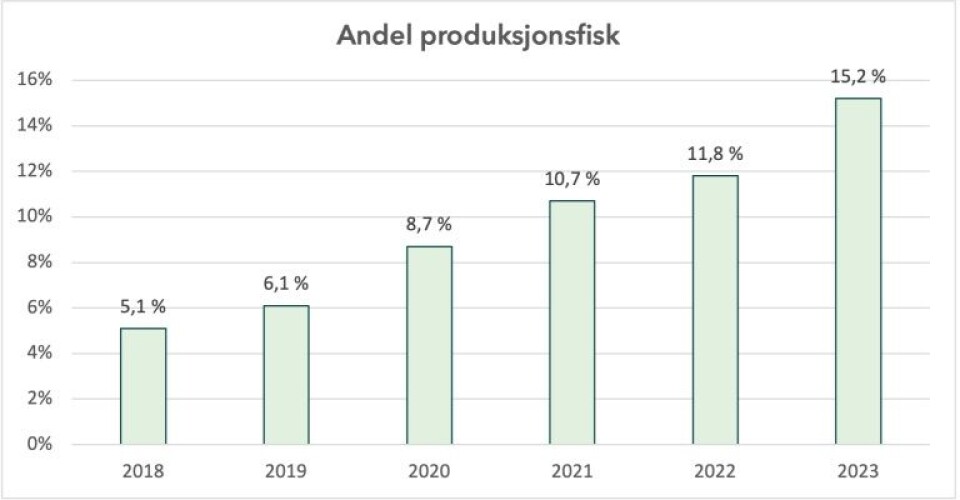

On average, Norwegian fish farms have 83 per cent superior fish and 17 per cent production fish, according to the Fish Health Report for 2023 (link in Norwegian).

However, there are differences depending on where the salmon comes from.

Among those coming from the sea basins outside Stadt and Nord-Trøndelag, only 11 per cent are production fish. While from Karmøy and Finnmark, around 22 per cent fall into this category.

It also varies throughout the year. Last year, the Norwegian Food Safety Authority recorded the highest proportion of production fish ever. As much as 37 per cent of the fish from Norwegian salmon slaughterhouses were downgraded to production fish in week 4, according to the website Intrafish (link in Norwegian).

Salmon with skin

When consumers buy salmon fillets or other salmon products, they receive no information about where the fish comes from, how healthy it has been, or how it was treated.

This is where whole salmon becomes relevant.

"If we buy a whole salmon with skin, we can at least be sure it hasn't had winter ulcers or undergone treatments that caused wounds and defects," says Poppe.

"If I can inspect the skin before purchasing, I would definitely prefer that fish," he says.

High mortality rates

Many fish die before reaching slaughter.

The Fish Health Report 2023 shows that the mortality rate was nearly 17 per cent, meaning over 100 million salmon die before they are supposed to. This number includes juvenile fish before they are transported to sea cages.

This is the highest morality rate ever recorded.

The reason for the high mortality is that salmon suffer from many health issues during their two-year lifespan.

They can develop winter ulcers, gill problems, and heart issues.

Additionally, they are affected by salmon lice, which feed on the fish's mucus, skin, and blood.

The lice are harmful to the fish, but treatments against them can be even more damaging.

Panic in hot water

Lice treatment methods include placing the salmon in hot water, which kills the lice but, according to researchers, causes severe pain and panic-like behaviour in the fish.

Other methods involve brushing or rinsing the fish, which damages their skin, leaving small cuts and wounds.

Once the fish sustain injuries from lice treatments, they become more vulnerable to bacterial infections in the seawater.

The bacteria in the water become particularly dangerous for farmed fish, which are often overcrowded and stressed, according to Trygve Poppe.

The result is winter ulcers – shallow or deep wounds that can penetrate the fish's abdominal cavity, cause eye infections, blood poisoning, and organ failure.

Salmon: The athlete of the ocean

Poppe describes interviews with people working at fish farms who say they avoid touching the fish because they are so fragile.

"Salmon was once the great athlete of the sea," says Poppe.

"Under normal circumstances, it's difficult to kill a large, healthy wild salmon. But farmed salmon has become so weakened and broken down," he says.

Swimming around with poor heart health

Poppe is not alone in his concerns about the condition of farmed salmon.

Edgar Brun, a veterinarian and former head of fish health and welfare at the Norwegian Veterinary Institute, recently spoke about salmon farming at a seminar:

"The salmon swims quietly in the pen. It swims around with poor heart health. Perhaps its vision is impaired. Its gills are only partially functioning. It has large, open skin wounds and struggles with multiple pathogens at once. The fish also experiences physiological chaos before being transferred to sea cages."

Despite the poor health and diseases in farmed salmon, they are not harmful to humans. Eating salmon with winter ulcers or infections does not pose a health risk to people.

However, sick and injured salmon should not be sold for human consumption without proper correction, as required by food safety regulations (link in Norwegian).

Such fish should also not be exported without the same corrective measures.

"An unfortunate trend"

Geir Ove Ystmark, CEO of Seafood Norway, represents the aquaculture industry. He disagrees that salmon is in crisis.

"It's an unfortunate trend. We must reverse this trend, but it takes time. On average, it takes nearly three years to raise a salmon ready for slaughter. Therefore, we cannot always see immediate results, even though companies have implemented measures," Ystmark said in an interview with sciencenorway.no.

Ystmark finds it concerning that the trend is moving in a negative direction and that mortality is increasing, but he is not sure if salmon are significantly more sick than other Norwegian livestock.

"Salmon farming is a very large-scale livestock operation, with many individuals. This affects the absolute mortality figures for salmon compared to other livestock," he says.

Vaccines against winter ulcers are ineffective

An increasing health issue is diseases related to winter ulcers, according to Ystmark.

"Vaccines against winter ulcers are no longer effective and need to be updated as diseases evolve. Preliminary results from new vaccines are promising," he said.

Then there is the issue of sea lice.

"We must keep sea lice levels low – not primarily for the sake of the farmed salmon but for the wild salmon. However, frequent treatment for sea lice can lead to some welfare challenges," said Ystmark.

The health history of salmon

Should we know more about a salmon's health before buying it in stores?

In a study on Norwegian consumers, only seven per cent said they had sufficient knowledge about fish welfare.

Both politicians and the Norwegian Consumer Council have made efforts to address this issue, including calls for clearer labeling of salmon welfare, as reported by the Norwegian Broadcasting Corporation NRK.

Trygve Poppe believes people should be informed about the poor health of salmon when they buy it.

"Farmers should label the fish with a guarantee that the product comes from a fish that was alive and of top quality at the time of slaughter," Poppe tells sciencenorway.no.

He believes the entire health history should be included on the label.

Several others agree with Poppe. In early 2024, the Socialist Left Party (SV) presented a proposal in Parliament for health labelling of farmed fish in stores. The proposal was not passed.

What can consumers do?

Should we stop buying salmon altogether?

"It won't make a difference if Norwegian consumers turn their backs on salmon," Poppe answers.

This is because 95 per cent of Norwegian salmon is exported abroad.

"And how much do they really care about animal welfare in China or Thailand?" he asks.

However, Poppe believes that a change in how Norwegians view salmon could still have an impact:

"If people here start caring more and more stories about the fish farming industry come to light, things might start to change," he says.

———

Translated by Alette Bjordal Gjellesvik

Read the Norwegian version of this article on forskning.no

Related content:

Subscribe to our newsletter

The latest news from Science Norway, sent twice a week and completely free.