Happy hens get hot

When a hen anticipates eating a juicy larva her temperature increases. Thermal imaging shows that happiness has a warming effect on chickens, just as it does with us.

Denne artikkelen er over ti år gammel og kan inneholde utdatert informasjon.

The hen struts around its spacious coop in a lab at the Norwegian School of Veterinary Science. Suddenly a red light blinks. She stops, stretches her neck and starts gaping in all directions.

No, this isn’t a school for teaching chickens to cross the road safely. This hen knows a blinking red light means it can soon expect a treat ‒ a delicious mealworm.

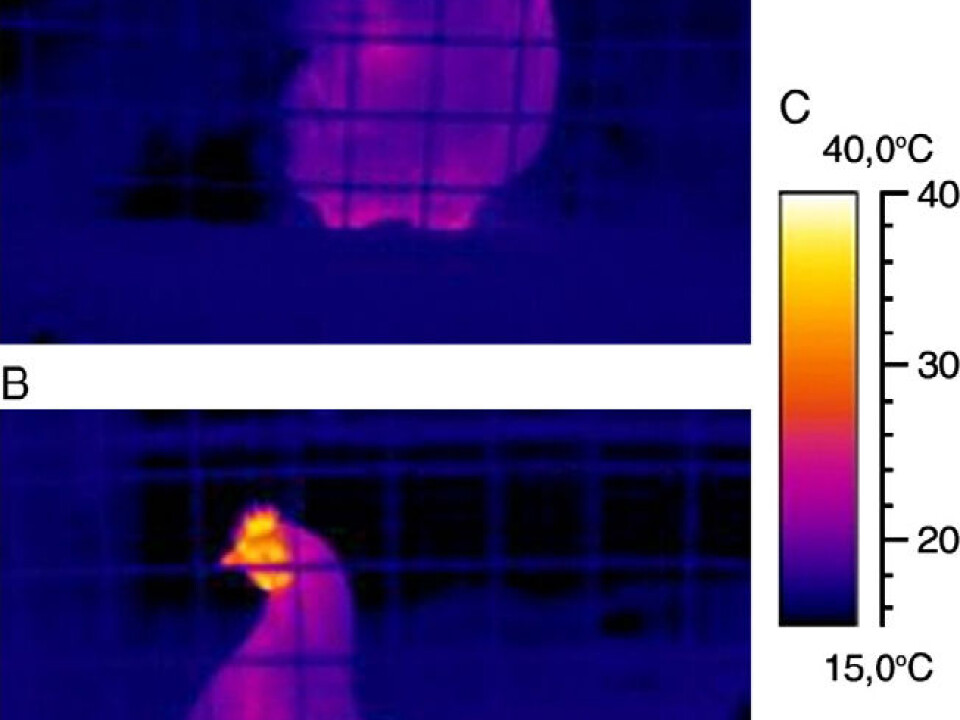

The hen is unaware of the candid infrared camera. Her image on a computer screen is luminescent. The camera captures heat radiation.

As soon as the red light blinks, her comb changes hue in the infrared imaging because its temperature is dropping. What’s going on here?

Experimental poultry

“Our test hens are trained to expect a tasty treat when the lights blink. The same thing happens with them as with us. A bird’s internal temperature increases while it initially cools on the skin surface. We call it emotional fever,” explains Randi Oppermann Moe.

She’s an associate professor in animal welfare and leads a group studying the subject at the Norwegian School of Veterinary Science.

The experiments she and her colleagues conducted with hens were calculated to reveal whether the poultry experience positive emotions ‒ happiness. If so, how could they express positive emotions in a perceptible language?

Emotional fever

The answer links to the way a body reacts.

“Emotional fever works just like a fever you get when sick,” continues Oppermann Moe.

“Your temperature initially drops quickly on the outside to concentrate heat inside the body. We get the chills or shivers with cold skin when our fevers are rising.”

But after a couple of minutes our internal temperature reaches its goal and we become flushed with fever. Along the same lines, just think how red in the face you can get when rising to speak in a large audience.

“We see the same phenomenon with the comb of a laying hen. It lights up in the infrared thermal camera,” says Oppermann Moe.

Fight or flight

What’s the point of turning hot with happiness? The answer is found in a contrary emotion, fear. In this sense our bodies don’t discern between positive and negative emotions. What counts is emotional intensity.

“Fear triggers a stronger physical reaction than happiness,” says Oppermann Moe. “Fear is the most important emotion we have for survival in a hazardous world.”

So if a fox turns up in the poultry yard, hens need to flap like wild to escape.

“In short, emotional fever gives her the heat she needs to speed up and give it everything she’s got,” says Oppermann Moe.

Pioneers

Fear and other negative emotions are vital to animal survival and they’ve been studied the most. Oppermann Moe and her colleagues are the first to demonstrate that chickens have some of the same physical reactions to happiness.

“The tests were done without people directly involved. We didn’t want the researcher’s emotions to affect the hens,” she says.

Uncooperative test subjects

After initial rounds which taught the hens to connect a blinking red light with a mealworm reward, the intervals between the light and the reward were gradually extended.

This is when the real tests began. Blinking lights were turned on every 15 minutes. The rewards would come as much as 25 seconds later. The temperature of the comb and hen’s head was registered about once a minute.

“The hens were strutting freely around in their coop and weren’t exactly posing for the infrared camera. It was pretty hard getting good pictures,” admits Oppermann Moe.

Nevertheless she thinks the results were unique.

“Animal welfare is an area of commitment at the Norwegian School of Veterinary Science so they are really important to us. Our studies and concerns involve the ways animals express feelings and how we can measure these feelings,” she says.

The investigation is a step towards understanding positive emotions among animals. This is a rather new direction in animal welfare research, according to Oppermann Moe.

Red and green lights

She thinks the results can contribute to giving poultry better lives in their service to us.

“Indeed, mealworms are too messy to use in poultry farms, but hens are also fond of grain. For instance they get happy when pecking for whole kernels of grain in the sawdust,” she says.

Oppermann Moe and her colleagues have also conducted experiments with red lights for mealworms and green lights for whole grains of wheat. The results haven’t been published yet but they show the hens could discern between the two expected rewards.

“They also clearly express positive expectations when they are rewarded with whole wheat. Chickens have good colour vision and are intelligent creatures,” says Oppermann Moe.

---------------------

Read this article in Norwegian at forskning.no

Translated by: Glenn Ostling