Oldest animals on Earth found in northern Norway

Researchers in Finnmark, Norway’s northernmost county, might also have found the answer to what happened to the first animal-like organisms – when our planet turned into a ‘snowball’ 600 million years ago.

The researchers want to keep the exact location in Finnmark where the ancient fossils were found under wraps.

“There’s a market out there for something like this,” says Anette Högström, a geologist at The Arctic University Museum in Tromsø.

She does not want the unique sites to be vandalized by fossil hunters.

Ancient fossils

For ten years, Högström has led an international research group in search of ancient fossils in the northernmost reaches of Finnmark county.

They have been looking for the very earliest animal and plant life on Earth.

“Northern Finnmark is one of the very few places in the world where we know it’s possible to find fossils from around 600 million years ago,” she says.

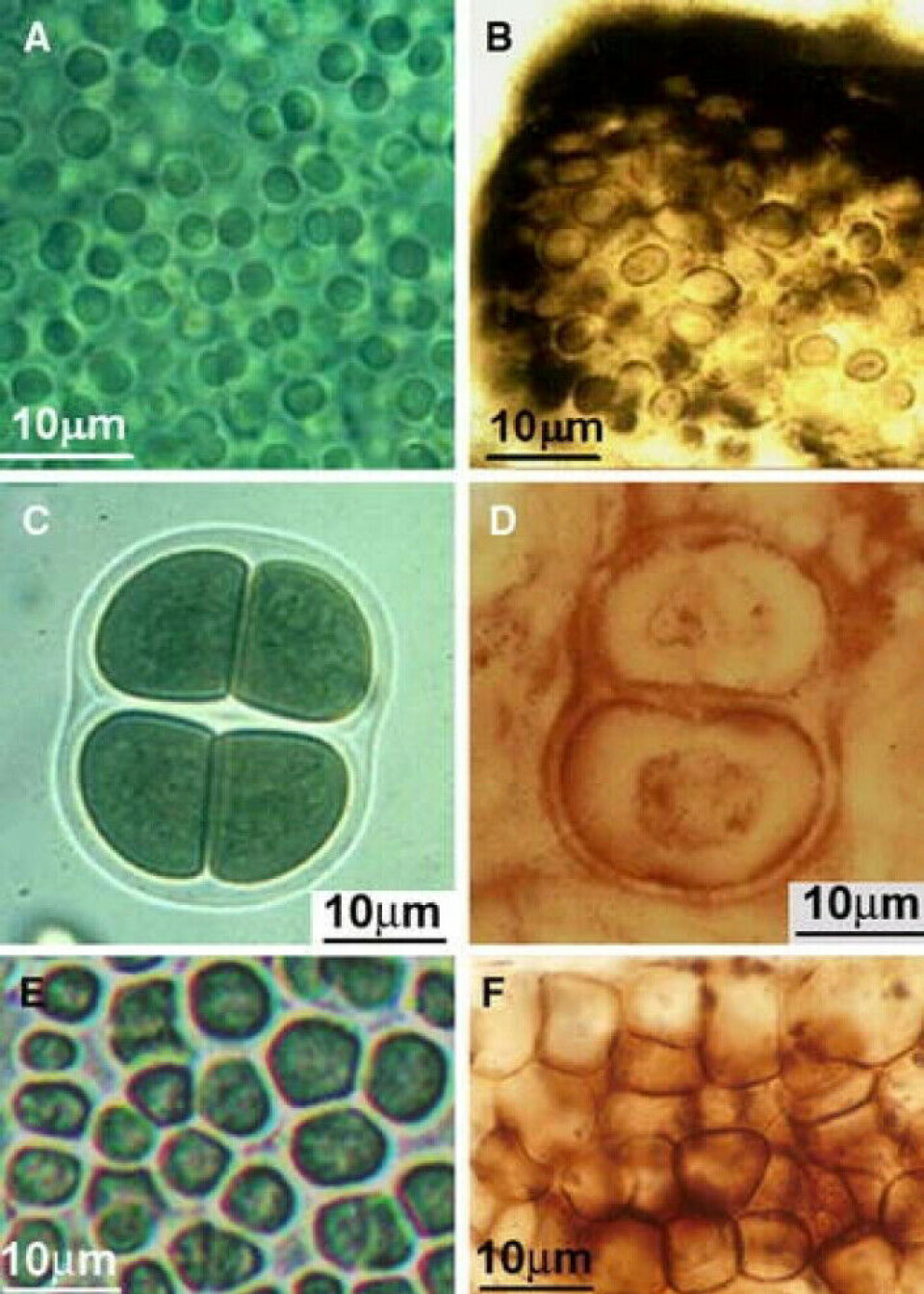

Högström says that their research involves small creatures. Instead of animals and plants, she and her colleagues talk about ‘eukaryotic organisms.’

These organisms lived in a shallow sea.

Life on Earth arises

Life on Earth arose 3.5 to 4 billion years ago.

For the first billion years, life forms consisted only of single-celled organisms.

Most of the organisms were bacteria. But a few of them eventually found themselves in extreme environments, around hot springs or in very salty water.

These microorganisms, called ‘archaea,’ could be the forerunners of the eukaryotic organisms.

Strange creatures

Then – 800 to 600 million years ago – multicellular life arrived on the scene.

Organisms developed specialized cells that could do different tasks, eventually leading to the first animals and the first plants.

The oldest known fossils of multicellular organisms that are not algae date from the Ediacaran Period, about 600 million years ago.

“That was when the first animal life appeared,” Högström says.

The geologist at the Arctic University Museum is clear that these creatures are not like animals as we think of them today.

Snowball Earth in Finnmark

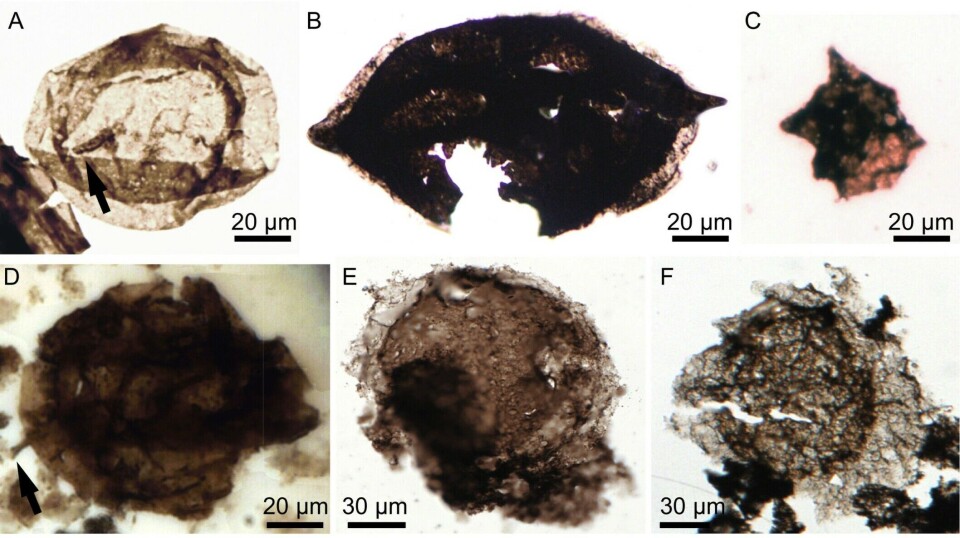

In recent years, Högström's research group has made several sensational discoveries in northern Finnmark. Their findings include microfossils that were the forerunners of animals and plants.

Recently, scientists made another spectacular fossil discovery that may offer answers to what happened to life on Earth during the dramatic period called Snowball Earth.

Our planet at that time was covered by a layer of ice from the poles to the equator for several million years.

Our Earth might even have gone into a deep freeze twice – first around 720 million years ago and then again around 650 million years ago.

Most viewed

But experts on the first life on Earth are divided into two opposing camps.

- One group of researchers believe that the precursors to animal life somehow managed to survive the Snowball Earth events and that the very first ‘animals’ are the forerunners of all later animal life – and humans.

- The other group of scientists believe that animal life could not have survived millions of years in this deep freeze, and that the animals must have arisen again, some 600 million years ago.

We will return to what Högström and her colleagues found this summer that might help decide this debate.

Challenging fossil hunting

The researchers found the microfossils in mountain deposits that they can date back to the Snowball Earth ice age.

Searching for microfossils like these presents major challenges. However, completely new techniques now allow researchers to search much more precisely.

It should be mentioned that other researchers have found several pieces of evidence that the Snowball Earth period actually existed.

A possibly decisive confirmation came from geologists at University College London as recently as this summer. They found rock formations on some small uninhabited islands in the Hebrides, off the west coast of Scotland, that show the transition of our planet into a deep freeze state in detail.

Darwin would have been delighted

The Arctic University Museum researchers collaborated with British, Spanish, German, Swedish and South African scientists on the latest study, which has now been published in the journal Palaeography.

In the research article, the scientists tell about their discovery of exceptionally complete layers of fossils in northern Finnmark from the time around the Snowball Earth period.

They found both body fossils and huge quantities of petrified trace fossils of animal crawling and digging tracks.

The fossil finds range from the simplest multicellular life to organisms with advanced symmetry.

- The researchers have found traces of what are probably the first movements of animals similar to worms.

- Further up in the same stratum, they found traces of the earliest known complex ecosystems.

- At the very top, they found what might be the first scratch marks of highly organized arthropods.

“Charles Darwin would have been delighted if he’d been given the opportunity to sail with the schooner Beagle to Finnmark to look at these discoveries,” the researcher says.

Fossils from before, during and after Snowball Earth

“The discoveries we made last summer have enabled us to compare fossils from before, during and after the Snowball Earth events.”

Högström freely acknowledges that this is a big deal.

Similar layered finds comparable to this one have previously only been made in Australia and China.

In short, Högström and her colleagues observed that life during Snowball Earth went from more complex organisms – eukaryotic microorganisms – and back again to simpler organisms like bacteria.

Seeing the animals disappear

“The new element is that we’ve been able to determine the age of our fossil finds – and that we’ve obtained fossils from the time of the Snowball Earth period itself.”

What they can now see in rocks from vanished continents in Finnmark is that these organisms disappeared when the planet froze up.

“This gives a us a sure indication that something was happening to life on Earth during the extensive freezing of the planet,” Högström says.

“Our fossil findings also show that bacteria take over during Snowball Earth.”

“We now have a clear picture of what might have happened,” says Högström.

The bacteria that took over are still there

The ‘animals’ that disappeared some 650 million years ago are thus completely different from all animal life that exists today.

This is in stark contrast to the bacteria that take over during the Snowball Earth period.

These bacteria are actually almost the same as the cyanobacteria (formerly erroneously called blue-green algae) that we find in abundance in salt water and fresh water today.

Högström sees a parallel to what we might experience today.

“When environments are disturbed, we often see that the cyanobacteria come and take over.”

“Take algal blooms in seas and lakes, for example. Usually precisely these bacteria are behind those blooms,” she says.

“Cyanobacteria have a tolerance for extreme conditions that animal life and plant life don’t have.”

Life after Snowball Earth period

So what happened to the progenitors of animal life after Snowball Earth events?

Much of scientists’ divided opinions is due to having so little available research and knowledge of the topic.

Researchers have only now become more certain that there actually were one or two very dramatic ice ages that turned the planet into a snowball.

Any survival by the ‘animals’ from pre-Snowball Earth must have taken place in small, ice-free pockets in certain places on the planet, as concluded by researchers at the University of Virginia Tech in the USA in a new study.

The researchers believe that these ice-free places were probably out in the open sea in the northern hemisphere.

Key climate scientists behind the Snowball Earth theory are sceptical of this survival theory.

Högström and her colleagues have now found that traces of the eukaryotic organisms in Finnmark disappeared during Snowball Earth and were replaced by bacteria.

So another possibility is that the first strange animal life—which may have appeared either before the Snowball Earths or in the period between the two Snowball Earths— simply disappeared.

Another animal life then returned several million years after the last Snowball Earth.

But yet another study has been published just within the last few weeks, this time from researchers in Brazil. It concludes that the forerunners of animals and plants may have existed as much as 800 million years ago – and that these earlier ‘animals’ and ‘plants’ survived both of the two dramatic Snowball Earth events.

Mystery surrounding the Cambrian explosion

About a hundred million years after the last Snowball Earth melted, life on Earth underwent something even more dramatic 539 million years ago.

The Cambrian explosion burst onto the scene.

In less than 20 million years, a great deal of life on Earth as we know it today appeared. Some researchers believe that the process moved along even faster.

The Earth explodes with life.

Some aspects of the Cambrian explosion remain a mystery for scientists.

What we do know is that life on Earth has suddenly acquired a head and eyes.

Animals become able to see. They are also able to crawl. They can eat each other. Predators and prey emerge. Prey animals grow shells that can protect them.

We know that a sharp increase in the amount of atmospheric oxygen after Snowball Earth must be one of the causes of the Cambrian explosion. Perhaps a large supply of nutrients in the ocean was responsible for the increase in oxygen. This enabled huge amounts of phytoplankton to develop photosynthesis and produce oxygen for the ocean and atmosphere – oxygen the animals could breathe.

- More calcium in the sea also made it possible for animals to grow shells.

- More plankton in the ocean provided more food.

- According to recent theory, the emergence of predators and prey that was eaten by the predators might have been essential for the emergence of advanced animal life.

More to be found in Finnmark

Högström points out that Snowball Earth may have helped to bring about the Cambrian explosion.

“This topic is an ongoing discussion between scientists who study the earliest animals.”

“What seems certain is that the increased amount of oxygen on Earth must have helped lay the foundation for the explosion of animal life,” she says.

Högström believes that the discussion about whether the first animal life managed to survive Snowball Earth depends a lot on whether there really were open ocean areas during these extreme ice ages.

And – whether there were organisms that carried out photosynthesis in these ocean regions and could thus become food for the animals.

“There’s still more to be found in Finnmark,” Högström says.

“Maybe we’ll be able to get answers to questions like this.”

References and sources:

Heda Agić et al: Life through an Ediacaran glaciation: Shale- and diamictite-hosted organic-walled microfossil assemblages from the late Neoproterozoic of the Tanafjorden area, northern Norway. Palaeography, 2024.

Science: Life may have survived far north of equator during 'Snowball Earth', 2023

Ross P. Anderson et al: Fossilisation processes and our reading of animal antiquity. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 2023.

Geoforskning.no: Dyrelivet ble utkonkurrert av bakterier [Bacteria outcompeted animal life], August 2024.

Other sources: geo365.no and SNL.

———

Translated by Ingrid P. Nuse

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no

Subscribe to our newsletter

The latest news from Science Norway, sent twice a week and completely free.