After thousands of years apart, wild and domesticated cats are now having kittens

Researchers have found that European wildcats and domestic cats did not have offspring with each other until the 1960s.

English researchers have looked at the relationship between the European wildcat and common, domesticated cats.

They found that wildcats and domestic cats did not have cubs with each other until 1960.

After this, they found crossbreeding between the two different cat species.

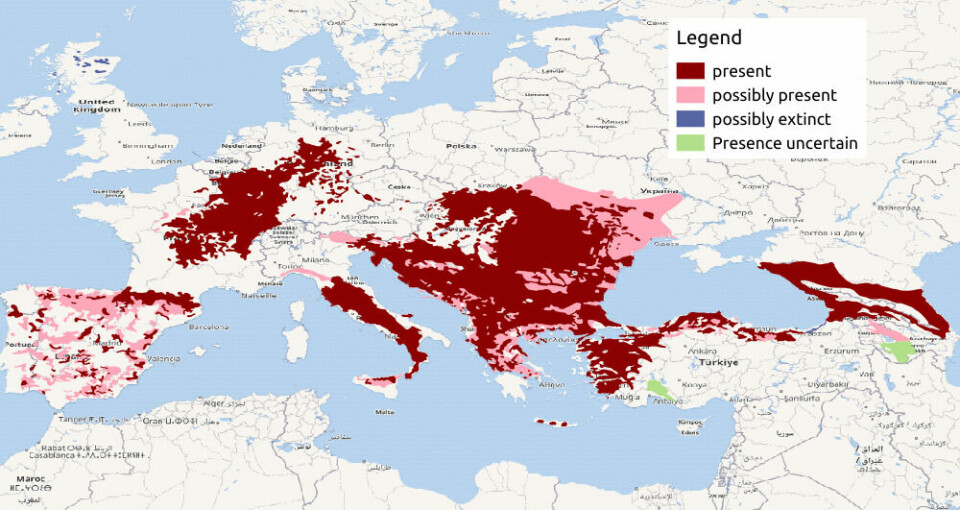

There are no wildcats in Norway, but they still exist in many other European countries.

Wildcats have lived in Europe much longer than humans have lived here.

An uncertain future

In some countries, like Germany and Italy, the European wildcat is doing well in the wild.

In other places, like Scotland, they often encounter domestic cats and produce offspring with them.

According to Eli Knispel Rueness, a biologist at the University of Oslo, these offspring don't fare well in the wild because they differ significantly from wildcats.

This means that many of the offspring die, resulting in fewer wildcats in Scotland.

“Habitat loss and persecution have pushed wildcats to the brink of extinction in Britain,” Jo Howard-McCombe from the University of Bristol said in a press release.

The rate of interbreeding between European wildcats and domestic cats in Scotland is significantly higher than in other European populations.

At present, all wild and captive Scottish wildcats show traces of domestic cat ancestry.

Large differences in small cats

The European wildcat looks quite similar to the cat you might have at home, but the wildcat is by no means tame.

We ask Petter Bøckman at the Natural History Museum about the actual differences between wildcats and domestic cats.

“There’s not much of a difference. If you look at an Egyptian wildcat and a domestic cat, you’ll see that the wildcat has a longer nose, larger canines, and smaller eyes. Like most wild animals, they are scarier,” he says.

The biggest difference is in how the cats live and behave.

Childlike cats

Cats that live at home with us humans are considered the only animal that has domesticated itself.

Bøckman explains that domestic cats appeared around the same time we started to cultivate food, about 10,000 years ago, and gradually spread into Europe.

When large quantities of grain accumulated in one place, pests like rats and mice appeared, which naturally attracted cats.

Since then, domestic cats have been dependent on humans, living close to us and receiving food.

Over time, domestic cats have adapted to humans, and those that live with us have become more childlike and less aggressive.

This can cause confusion when a domestic cat meets a wildcat.

Wildcats do not live in groups, but they are territorial, meaning that they fiercely guard their living area. No other cats are allowed to be there.

Domestic cats, on the other hand, are often more accustomed to other cats and might think the wildcat is the same.

The wildcat may view the domestic cat as a competitor, according to Bøckman.

Where does the domestic cat come from?

Although domestic cats and the European wildcat look similar, they are not considered the same species.

Eli Knispel Rueness explains that many believed domestic cats originally came from the same species as the European wildcat.

However, this is not accurate. Domestic cats actually descend from the African wildcat, which began to accompany humans into Europe after the agricultural revolution 10,000 years ago.

References:

Most viewed

Gerngross et al. Felis silvestric, The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species, 2022.

Howard-McCombe et al. Genetic swamping of the critically endangered Scottish wildcat was recent and accelerated by disease, Current Biology, vol. 33, 2023.

Jamieson et al. Limited historical admixture between European wildcats and domestic cats, Current Biology, vol. 33, 2023.

———

Translated by Alette Bjordal Gjellesvik

Read the Norwegian version of this article on ung.forskning.no