Misleading moths with fake fragrances

The flights of moths and butterflies might appear willy-nilly but the insects are guided by their sense of smell. A pesticide specialist is now developing artificial rowanberry scents to capture moths and protect apple orchards.

Denne artikkelen er over ti år gammel og kan inneholde utdatert informasjon.

The apple fruit moth (Argyresthia conjugella) can out-smell any bloodhound you can find.

“We think of dogs’ olfactory powers as fantastic but that’s nothing compared to the apple fruit moth,” says pesticide expert Geir Kjølberg Knudsen, of the Norwegian R&D institute Bioforsk.

He has studied this moth species for years and has even speculated on their potential use in detecting landmines.

Knudsen has concluded that the moths probably don’t live long enough to learn and perform that particular skill. So as far as using members of the animal kingdom against dreadful weapons is concerned, it’s best to continue with rats and dogs.

Scourge of the orchards

Until somebody finds a beneficial use like that, these nocturnal insects will be best known for the damage they can do. The apple fruit moth eats apples and lays its eggs on them. The resulting larva tunnel into the fruit too. These are the “worms” in a wormy apple, and for owners of apple orchards they are a nightmare.

But the moths’ favourite dish is the rowanberry. Apples are their second choice in years when rowan trees don’t produce enough of their bright orange clusters of berries.

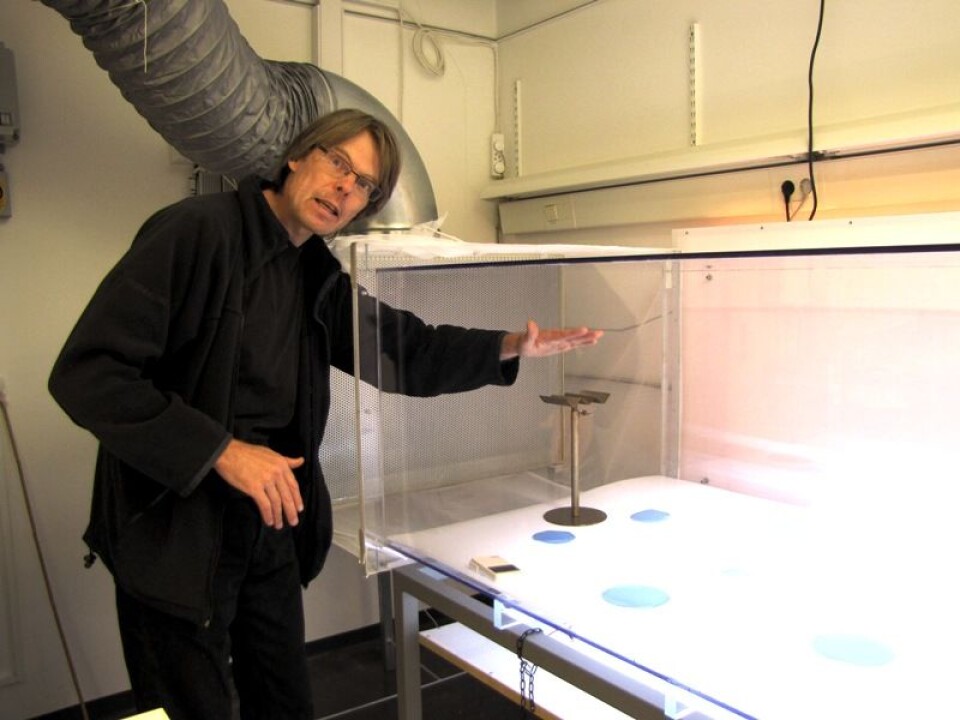

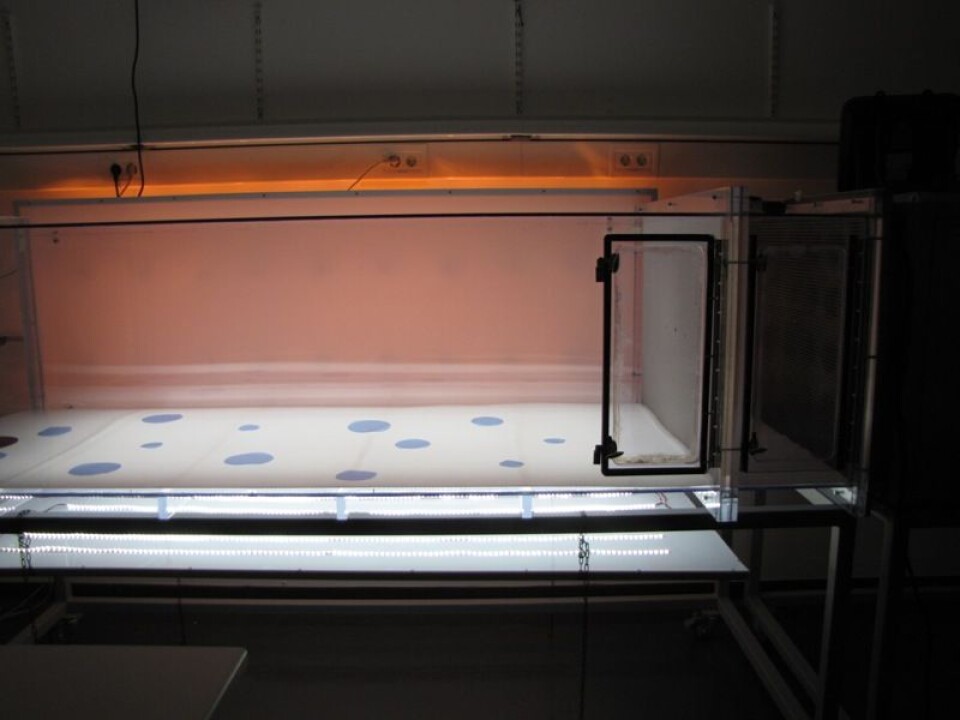

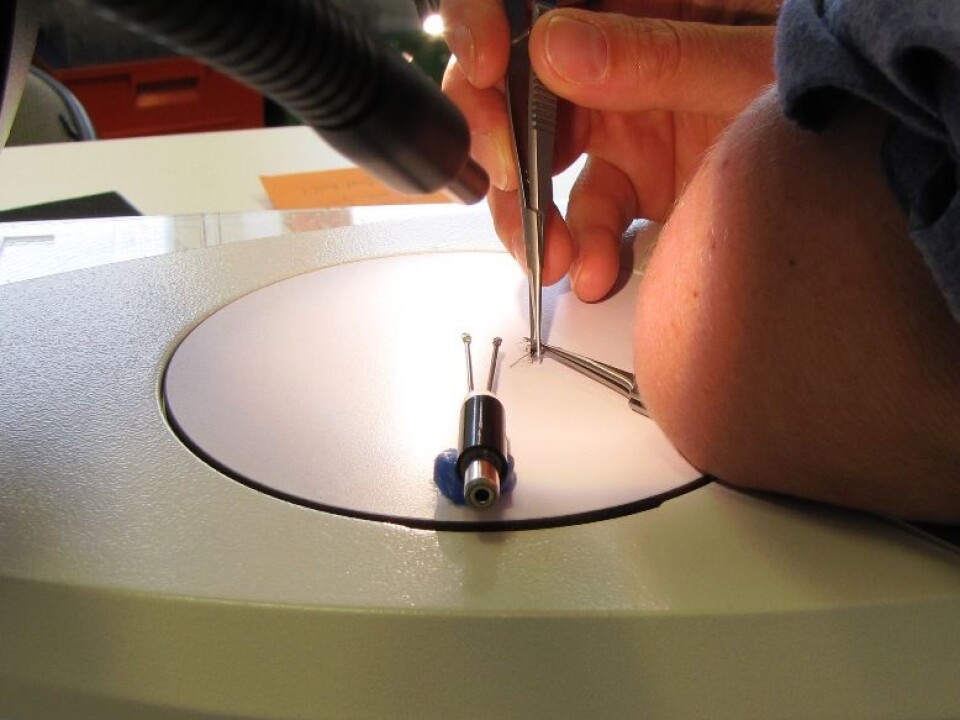

Scientists have used the moth itself as a smelling assistant in their attempts to produce an attractive artificial rowanberry fragrance.

The researchers are convinced they can protect apples by clever and harmless means, such as rowanberry-scented traps.

“We’re working on it because we think the right way to manage pests involves a reduction of agricultural pesticides,” says Knudsen.

Apple tests this summer

Scientists in the Nordic countries are about to start testing the rowanberry scent outdoors. Their experiments will be made in commercial orchards where they hope to lure the moths away from succulent apples and into their deadly traps.

Researchers from Norway, Sweden and Finland will divide apple orchards into two sections, one of which will be equipped with rowan-scented traps.

The scientists will be looking for the optimal way of controlling the moth problem by studying the damage to the two sections of the orchards and the success of luring moths into their traps.

They want to find out when the moths start their onslaughts so that farmers can time a counterattack perfectly. They will also monitor the extent of the attacks so farmers can consider when or if they need to use insecticides.

The most obvious advantage is that any moth that is caught in a sticky trap won’t be satisfying its appetite for apples.

How well do the traps work as an alternative to sprays?

Sometimes farmers get so dejected by overwhelming moth damage that they don’t bother to remove the wormy apples on the trees and ground.

The moths’ next generation are then perfectly set for flying up into the trees the following year and yet another crop will be spoiled.

The smarts are superior to sprays

At Norwegian apple orchards a method has been found for estimating the magnitude of the moth problem from year to year and thus minimise the use of insecticides.

But it’s not always easy to predict populations of the apple fruit moth, and apple orchards continue to be exposed to moth attacks now and then.

Another alternative to insecticides involves pheromone lures. Farmers place devices that emit scents mimicking those the insects follow when looking for a mate.

The artificial pheromones confuse the pests and many of the males fail to find their way to females, which reduces the number of fertilised eggs that would become next season’s pests.

Some might think of this mimicry as an interference with Mother Nature, but Knudsen says it’s much better than using toxic or polluting chemical compounds.

Pheromone deception and scent traps are much gentler.

“I think the key idea is that there’s no reason in rolling out the big guns, in other words poisons, when the job can be done so much more elegantly with fragrances,” he says.

The rowan-scented traps and pheromone mimicry both exploit the insects’ strongest weapon, their olfactory superpowers.

Currents of molecules guide flight

Insect species use their sense of smell constantly – to navigate to mates, to forage for food and to find places to lay their eggs.

It just doesn’t look that way as they buzz, flutter or flit around in all directions.

They are on the tracks of something vital to them – scents, molecules drifting through the environment.

“If they lose the track, they immediately fly back and catch it again. That’s what looks like random flitting around,” says Knudsen.

Translated by: Glenn Ostling