Thorium from Telemark

Mines have been in operation at Ulefoss in Norway’s Telemark County since 1650. Now the next generation of nuclear power plants can make the mining of thorium profitable here. But first of all deposits have to be mapped better.

Denne artikkelen er over ti år gammel og kan inneholde utdatert informasjon.

Although the nuclear catastrophe in Japan has amplified opposition to nuclear power, the world’s growing economies are in need of energy sources and are likely to push for more construction and development of nuclear plants.

This will certainly lift the price of the nuclear fuel uranium. In turn, it will become more profitable to extract the alternative fuel thorium.

Norway is thought to have the world’s third largest reserves of the element, which was named after the Norse god of thunder, Thor.

But geological maps of these deposits are generally antiquated, ancillary and incomplete.

“The company Norsk Thorium wants to do something about that,” says Gunnvald Solli. He’s the general director of a firm that hopes to exploit thorium from Telemark.

From Tanzania to Telemark

The Fen field lies nearby the town of Ulefoss. The locality is the crater of an ancient volcano. When the prehistoric continent of Baltica was splitting up 550 million years ago it was active and spewed lava.

The Fen volcano had a sister which was last active much more recently − in 2007. Its twin is the Tanzanian volcano Ol Doinyo Lengai. This says something about the extensive drift of continental plates since the Fen volcano died out, from Tanzania to Telemark.

Ol Doinyo Lengai can give us an impression of what the Fen volcano looked like. It spews a rare form of lava containing plenty of carbon. It is dark and flows more easily than water.

From iron mines to rare earth metals

This kind of lava is also quite water soluble and erodes and weathers easily. In the Fen field at Ulefoss all that remains are parts of the volcanic feeder. The field contains iron ore which has been mined since 1650.

The iron mines closed down in 1927 but the Ulefos iron works still produces manhole covers and the company is one of Europe’s oldest industrial firms. Many Norwegian homes and cabins have cast iron wood stoves sporting the trademark Ulefos.

During WWII when Norway was occupied by Germany the element niobium was extracted here and used by the occupant in steel production for its war industry. After the war the Norwegian state ran the Søve mines and extracted niobium from the mineral sovite until 1963.

But other minerals are now of greater interest. Rare earth metals are also found in the Fen field. These elements can be used in manufacturing batteries, catalytic converters, magnets, lasers and mobile phones.

And where you find rare earth metals you also find thorium. Norway could have the world’s third largest deposit of thorium, most of it at the Fen field.

Poorly mapped

No one can say how large the deposit is. The government agency NGU carried out a geological mapping of uranium in the area in the 1970s and 1980s. Thorium is often found along with uranium.

These indirect finds have been given a lot of coverage afterwards, including in reports to the International Atomic Energy Agency, IAEA. But that doesn’t guarantee the figures.

“We have some samples from 2006, but it’s hard to say whether the thorium deposits are exploitable. We think so, though” says Solli.

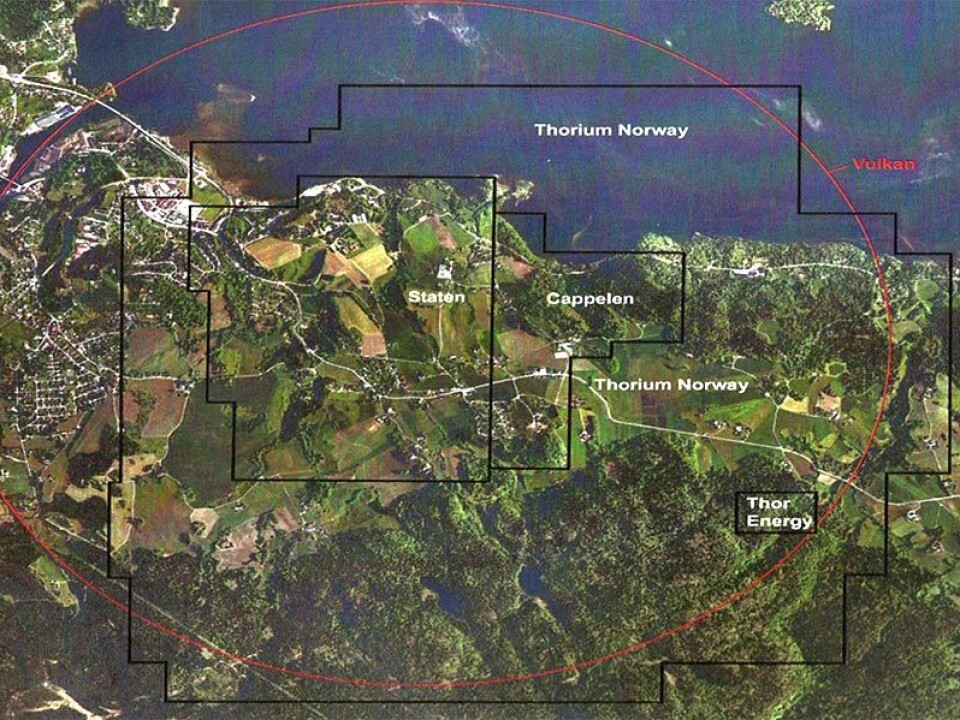

A half year ago Norsk Thorium bought up another firm, Thorium Norway. Norsk Thorium now has mining rights on minerals in a 2,500 acre are of the Fen field. The entire field consists of about 6,000 acres.

Other ores

Norsk Thorium isn’t only interested in thorium. Solli says that initially the most interesting commercial mining would be for other rare earth metals.

Production can be profitable because demand is rising and the major producer, China, is curbing exports, for environmental and economic reasons.

“The Americans see the writing on the wall. To produce a car battery you need a lot of lithium. Catalytic converters require other substances, and all of these are found at the Fen field,” says Solli.

With prices soaring Norsk Thorium expects to have a viable business in rare earth metals, until the first commercial thorium power plants in two or three decades bump up demand for it too.

Better mapping

Thorium can be seen as black spots in the rock rauhaugite. Norsk Thorium will need the expertise of a niche industry in China, Australia and Canada to extract it. These producers have patented, industrially secret processes for extracting pure thorium.

In the meanwhile Norsk Thorium needs to map its thorium deposits better, in collaboration with Danish geologists.

“As soon as the snow melts we’ll take samples from as deep as 100 metres. We’ll get a report that will be delivered to the ten companies in the world that has the expertise to mine these minerals.

“In the course of a half year we should make some big choices, selecting our partners or selling our rights,” says Gunnvald Solli, who is now prospecting for investors.

----------------------------

Read this article in Norwegian at forskning.no

Translated by: Glenn Ostling

External links