Forgotten recipes: Roe waffles, brain sausage, and stuffed heart sacs

We used to eat the whole animal. Now we stick to the muscles and minced meat.

When you buy a whole turkey, it comes with a bag of giblets. You get the bird's heart, liver, neck, and gizzard – a part of the stomach.

“This is perhaps the closest we come to direct contact with offal nowadays,” Eva Narten Høberg said during a lecture at the National Library of Norway on March 11, 2025.

At least as far as we know.

“Offal can be more camouflaged than the bag you find in the turkey,” said Høberg, who is a researcher at the Norwegian Institute of Bioeconomy Research (Nibio).

Offal was a natural part of the diet in the past, but it has become unfamiliar to people today.

The nutritious blood

Høberg believes we should use the whole animal:

"It's ethical and sustainable management of the valuable food resource that animals represent."

That's why she believes it's time to rediscover this good and nutritious food.

The blood, for example.

After an animal is stunned before slaughter, the carotid artery is cut and the blood is drained.

Blood is a good source of iron, according to Høberg, and it is still used as an ingredient in cured sausages. Grilstad’s black sausage and Gilde’s stabbur sausage both contain blood.

The attendees were given samples along the way, prepared by the restaurant Credo.

The blood pancakes were made from pig's blood, broth, barley, milk, and syrup.

No food waste

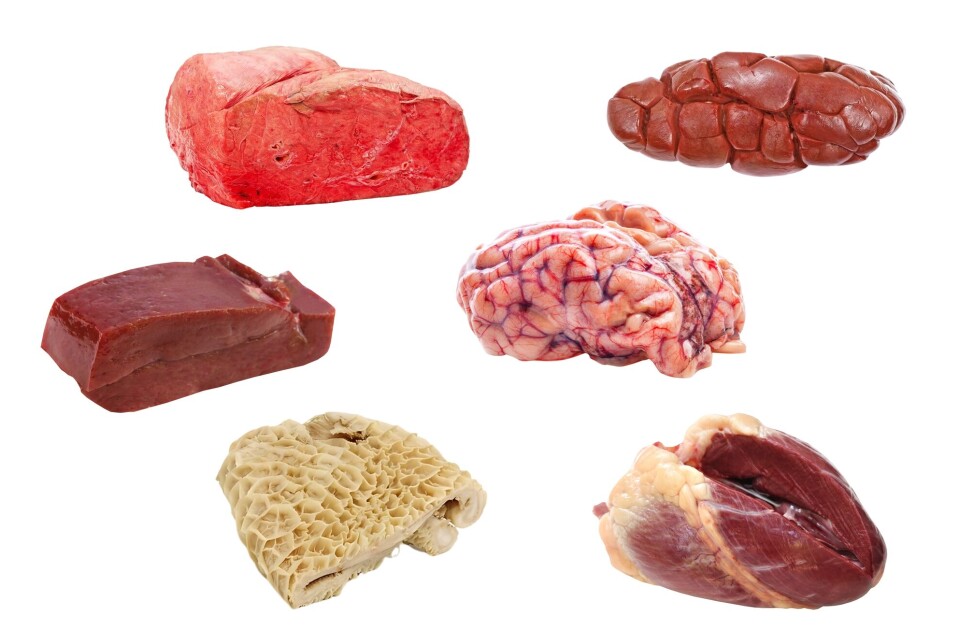

Offal is defined as an animal’s internal organs and blood, but also includes the tongue, head, feet, shanks, bones, and bone marrow.

The oldest and most common offal came from ruminants and fish, according to the Nibio researcher.

Cows, sheep, and goats were the first domesticated animals. They eat plants and do not compete for food with their owners.

Pigs don’t graze, so farms had to have enough food scraps to feed them.

“Food waste was a concept that didn’t exist,” said Høberg.

People kept the livestock they could afford. There were pigs during the Viking Age, but only on the largest farms.

Easier to deal with minced meat

People hunted seabirds and forest birds, but domestic chickens did not arrive until the Middle Ages.

“Today we’re so far removed from food production that handling an entire carcass can quickly become difficult. It can also reveal more than we're comfortable knowing about what we're really eating,” said Høberg.

That’s why minced meat has become so popular.

“It’s more pleasant than having to deal with a whole animal carcass,” said Høberg.

Today’s consumers can still handle the sight of whole chickens and turkeys.

“We can still deal with them in their whole form,” she said.

Hearts in cream sauce

The first Norwegian cookbooks appeared in the 1800s. They explain in detail how to take care of the entire slaughtered animal, including the meat, blood, and offal.

Høberg presented the figures for the consumption of offal in Norway today .

52 per cent of Norwegians never eat liver or offal for dinner. That's twice as many as in 1989.

Less than one per cent of Norwegians consume offal for dinner every week.

Only seven per cent of the population have offal or liver on the dinner table a few times a year. In 1989, it was 21 per cent, according to the consumer survey from Ipsos.

“The heart is very versatile, either fried or stuffed. It can get tough over the years, because it works hard, but with proper preparation, it’s delicious food,” said Høberg.

Hearts can be prepared with a cream sauce or in a stew, as shown here on NRK (link in Norwegian). Cured reindeer hearts are a delicacy from the Sámi tradition.

Gullar is a dish that has almost disappeared.

“They’re heart sacs that are filled with offal, meat, onion, salt, pepper, and a little flour. The heart sac is used like sausage casings,” Høberg said.

Liver pâté lives on

The liver is the body's largest gland. It cleans the blood.

“Liver has a distinctive taste that can resemble game meat,” said Høberg.

Liver contains a lot of iron and vitamin A and works well in stews, meatloaf, and pâtés, according to cookbooks (link in Norwegian).

Pâté made from pork liver is the most accepted use of offal today, Høberg believes. Liver pâté is still used as a spread in many Norwegian homes.

Kidneys used in different ways

Urine is formed in the kidneys. That's why they have to be soaked in water before use.

“The substances need to be washed out, it's nothing more mysterious than that,” said Høberg.

Slightly older cookbooks have numerous recipes using kidneys from lamb, reindeer, and veal. Kidneys can be fried and served with cream sauce, flambéed, or used in stews.

Adrenal glands are rarely used in cooking.

“But it might actually be quite smart to eat them too. They contain vitamin C, which is surprising, because we’ve been taught that vitamin C isn’t found in animal-based foods,” she said.

Unknown in Norway, a delicacy in France

The thymus is a gland in the chest of both humans and animals, and it is important for our immune system.

“When we're young, the thymus is full and well-developed. The same goes for animals. But after puberty, it becomes less soft and delicate,” said Høberg.

Calf's thymus is a delicacy in France and Italy. It is also called sweetbread.

Ingrid Espelid Hovig was the host of NRK’s Fjernsynskjøkkenet (TV Kitchen) for 40 years. She wrote more than 60 cookbooks.

According to Hovig, heart and liver are everyday food, while thymus and kidneys are for special occasions.

Pizza with lung hash

Lung hash is still sold in many Norwegian grocery stores.

“The lungs have had the honour of giving the dish its name, but lung hash contains a mixture of many types of offal and meat, well seasoned with nutmeg, cloves, and ginger,” Høberg said.

Gilde's version contains 10 per cent lung meat, 63 per cent 'meat raw materials', and pig hearts.

Espelid Hovig’s cookbook Den rutete kokaboka includes a recipe for pizza with lung hash.

In 2021, researchers at Nofima conducted a test. They added beef lungs to grilled sausages. Then they let their own panel of tasters and regular consumers taste the sausages without telling them they contained lungs. No one found the taste to be negative, the researchers said in an article from Nofima (link in Norwegian).

Cervelat comes from the brain

Today, offal that could be eaten by humans are used as dog food.

“Using nutritious parts of the carcasses as animal feed is wasteful. With prosperity in Norway came the tenderloin. We've developed the attitude that we can just throw away what we don't want. Several of the offal products we now decline to eat contain more of the important nutrients than the muscle meat we actually do eat,” meat researcher Rune Rødbotten stated in the article.

The brain needs fat to function. That's why it's quite fatty, but well suited for sausages.

“The word cervelat comes from the Italian cervello, which means brain. But there's probably no trace of brain in Norwegian servelat,” said Høberg.

You can find a lot of recipes for brain sausages in old cookbooks. And the brain can be used in the same way as kidneys, according to Høberg.

It doesn't stop at the brain. The tongue is meaty and delicious too. Many Norwegians still cook it for Christmas. Boiled beef tongue can also be bought as a cold cut in the store.

Pig heads are still used

Høberg thinks the head, feet, and legs – called shanks – are parts of the animal that should be used more.

The tradition of using the pig's head in head cheese still lives on.

Cow’s udders can be used both as a spread and as a dinner dish, according to older recipes.

There are two common ways to prepare offal.

French and Norwegian preparation

“One way is to let the different organs shine individually in their own dishes. That's common in French cuisine,” said Høberg.

In Norway, the traditional use of internal organs is to combine several of them in a mixture.

“It's a practical and effective use of all parts of the carcass. It’s also a way to camouflage the ingredients – an advantage for the faint of heart," she said.

Høberg pointed out that the coastal culture is just as important as farming culture in Norwegian food traditions.

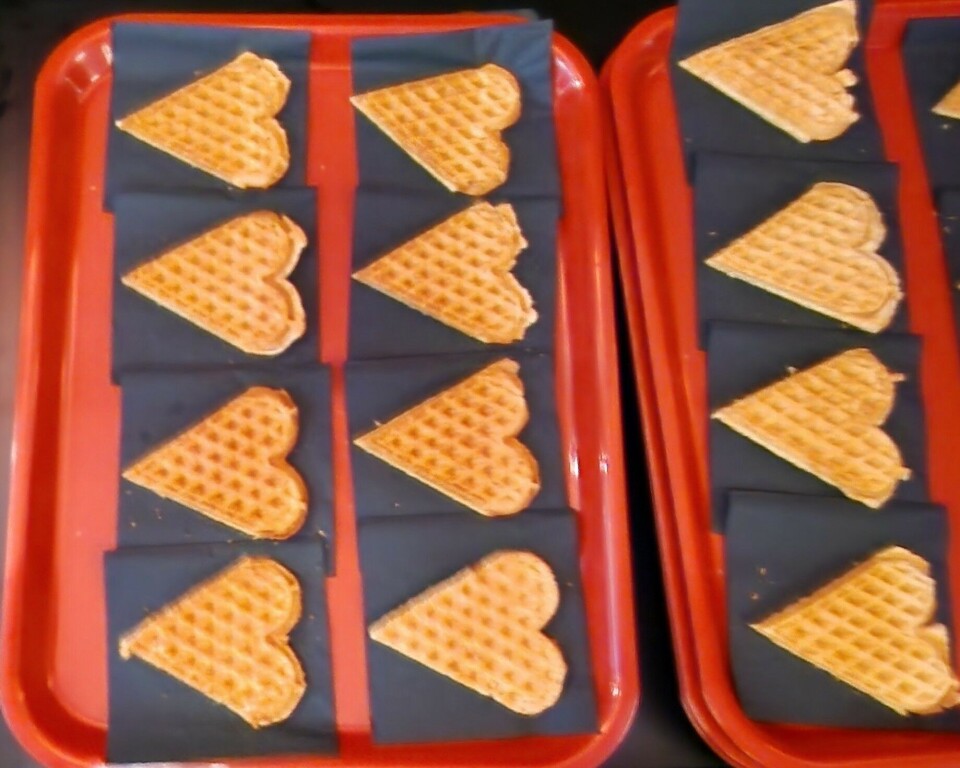

That's why waffles made from cod roe were the final tasting to be passed around at the National Library.

“Roe is the fish's eggs, and they're rich in protein. A well-known practice along the coast in Nordland county is to make the waffle batter with fish eggs instead of chicken eggs,” said Høberg.

Therese and Magnus Fagerhaug each received their own waffle heart.

“I can taste the seafood, but the flavour was very good,” said Therese Fagerhaug.

———

Translated by Ingrid P. Nuse

Read the Norwegian version of this article on forskning.no

Related content:

Subscribe to our newsletter

The latest news from Science Norway, sent twice a week and completely free.