Making good sperm better

Why are boars in Norway more fertile than elsewhere?

Denne artikkelen er over ti år gammel og kan inneholde utdatert informasjon.

Internationally, boar fertility is declining.

“Not so in Norway. We want to find out why, so we don’t go down the same road,” says Elisabeth Kommisrud, a professor at Hedmark University College. Male animal fertility is her field of speciality, and more fertile pigs mean better economics for Norway's nearly 3,000 pig farmers.

A breeding strategy that increases boar fertility would also be a huge step for the international pig breeding society.

Environmental effects on heredity

The sperm is just a motor that carries genetic material, says Kommisrud.

She and her colleagues are studying boars that have sperm DNA damage. “Sperm is a tightly wrapped packet of DNA with a tail attached. If it isn’t packaged well enough, then the sperm can still fertilize the egg, but the result might be early foetal death,” says Kommisrud.

But piglets inherit more than just the traits of several generations of boars and sows in their family tree. Changes in genetic material caused by environmental factors are also passed along.

Kommisrud explains that epigenetics are trait variations brought about by external causes, such as pollution. A classic example is a severe famine period in the Netherlands during World War II. Hospitals have very good records of children who were born before, during and after the hunger period. The records show that disease tendencies during the famine affected not only the pregnant women, but were also passed on to their children.

Damage to sperm

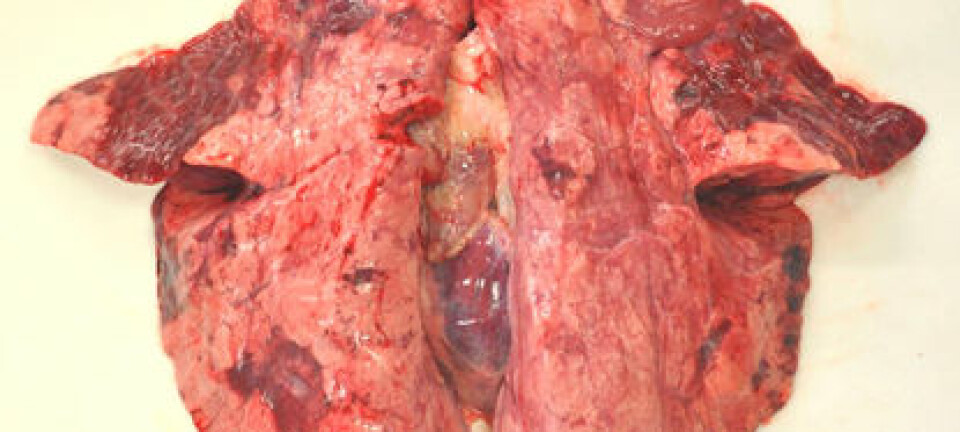

Researchers in Hedmark are studying damage to sperm DNA. They have found salmon sperm to be very hardy, but the boar’s sperm are more vulnerable.

According to Kommisrud, some boars with varying degrees of sperm DNA damage have already been identified. Now researchers are looking at them to determine if the damage has internal or external causes.

Although fertility rates are declining internationally, scientists and pig breeders know that the fertility rate in Norway is very high. But why?

“The interesting question is whether the level of damage to sperm DNA is lower in Norway than in other countries. That is the case with cattle, and it may be the case with swine, too,” says Kommisrud.

Breeding better sperm

Female fertility is complicated. For example, metritis — inflammation of the uterine wall — leads to lower fertility in cattle, and is much more prevalent in other countries. So Kommisrud focuses her research on male fertility.

She is also working to extend sperm life. She says, “The basic idea is to extend the life of sperm cells from 24 to 48 hours. First they have to stop moving, and then they’re frozen.” Sperm cryopreservation has been successful in cattle, but the technique cannot simply be transferred to pigs. Bulls and boars are quite different, says Kommisrud.

The sperm are made immobile in a gel that looks like a small strand of spaghetti. When inserted in the cow, the gel gradually melts so new sperm are constantly being released, making the insemination time a bit less critical.

One collection of semen from a boar can yield up to 40 litters, and with ten to twelve piglets or more per litter, that can mean several hundred pigs. So selecting quality boars for the breeding program is extremely important, says Kommisrud.

---------------------------------------------

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no